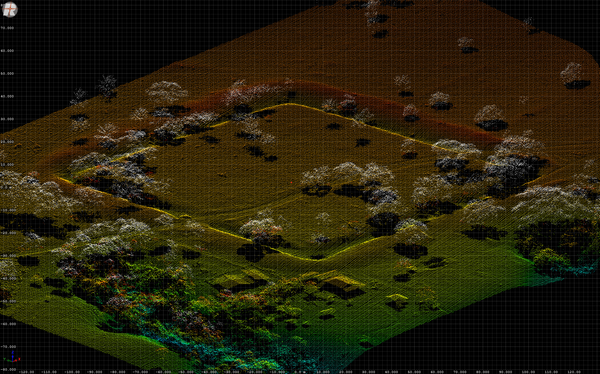

The precise function of the structures has yet to be made clear. Very few artifacts have been discovered during excavations in the Amazon, meaning it's unlikely the earthworks were villages.

Dr. Jennifer Watling is one of the researchers who have analyzed the geoglyphs hoping to uncover more information about the unusual structures and those who built them.

"We immediately wanted to know whether the region was already forested when the geoglyphs were built, and to what extent people impacted the landscape to build these earthworks."

In Dr. Watling's paper titled, Impact of pre-Columbian 'geoglyph' builders on Amazonian forests, she has uncovered various insightful discoveries about the earthworks.

"There are still many questions to be answered about the culture that built the geoglyphs. We know so little about them because archeologists haven't yet found the places where these people lived on a day-to-day basis. It seems that the majority of geoglyphs were built around 2000 years ago and that some may have been built as early as 3000 years ago. The latest date for the use of one of these sites is 650 years ago. The first geoglyph builders may have already been living in the area, or alternatively have migrated there from another region," Dr. Watling told Sputnik.

Dr. Watling and the rest of the team at the Museum of Archeology and Ethnography are unsure how long it would have taken to build the geoglyphs but their discovery has enabled the researchers to understand more about the area in the Amazon.

"There has been a debate raging for decades over how populated or not were Amazonian forests before the arrival of Europeans to the continent. While most people accept that areas along the floodplains of major rivers supported high populations, the upland forests are normally thought of as less-favorable environments to their poorer soils and more sparsely-distributed resources," Dr. Watling told Sputnik.

"The presence of the geoglyphs in upland forests in Rio Branco, Acre therefore challenges this view that these were marginal environments for human cultures, along with the idea that these forests are in some way completely 'natural' or 'untouched', " Dr. Watling told Sputnik.

The study has uncovered that 'geoglyph cultures' had a long history of transforming the natural bamboo forest into a more abundant environment, by setting small fires and managing forest re-growth of such species, as palms and Brazil nut in some areas.

"The two geoglyphs we studied were actually built within forest that had already been transformed in this way, and their builders only made small clearings to be able to build the earthworks," Dr. Watling told Sputnik.

The archeologists believe that the geoglyphs were public gathering spots where people met occasionally to carry out ceremonial and ritual activities. This interpretation is based on the geoglyphs' highly formal, geometric structure and the discovery of what appear to be ritual deposits in the entrances to some of the sites.

"We know that they weren't the sites of long-term occupation because not enough artefacts were discovered during excavation for this to be the case," Dr Watling told Sputnik.

Commenting on the similarity between the discovered geoglyphs and Stonehenge in the UK, Dr. Watling told Sputnik that the only broad resemblance is the recurring pattern of an external bank and internal ditch in the earthworks, which mirrors henge enclosures and as to the builders of the compared structures — their social, economic and belief systems would be very different.