In giant crystals deep in a Mexican cave, scientists found creatures mostly unknown to science that have evolved to endure their harsh environment by feeding on iron, sulfur and other chemicals. Many have remained dormant for tens of thousands of years — up to 60,000 perhaps — but can still be revived.

"These organisms have been dormant but viable for geologically significant periods of time, and they can be released due to other geological processes," NASA Astrobiology Institute director Penelope Boston said in announcing their findings at a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science February 17, National Geographic reports.

"This has profound effects on how we try to understand the evolutionary history of microbial life on this planet.

Boston and her team have spent years exploring Mexico's volcano-heated Naica mine and its pillars of crystal, searching for extremophiles. They found them inside the mine's massive crystals: tiny creatures in a state of geolatency, which describes a state of remaining viable in geological materials for a long, long time.

The team removed some in 2008 and 2009, and, "Much to my surprise we got things to grow," Boston told the Telegraph. "It was laborious. We lost some of them — that's just the game. They've got needs we can't fulfill. That part of it was really like zoo keeping."

Some 100 different bugs, mostly bacteria, were harboring in the crystals of the cave, suspended for between 10,000 and 60,000 years. Ninety percent of them had never been seen before, the Telegraph reports. Most life could not survive in the dark and the heat of the cave, but these hearty few evolved to consume the sulphides, iron, manganese or copper oxide around them.

The organisms are genetically distinct from anything known on Earth, Boston's team says. They are most similar to other microbes found in caves and around volcanoes.

"They're really showing us what our kind of life can do in terms of manipulating materials," Boston said.

"These guys are living in an environment where there's not organic food as we understand it. They're an example at very high temperatures of organisms making their living essentially by munching down inorganic minerals and compounds. This is maybe the deep history of our life here."

Some question whether the microbes really come from inside the crystal, as Boston and her researchers assert, and not from the pools of water that surround them.

"I think that the presence of microbes trapped within fluid inclusions in Naica crystals is in principle possible. However, that they are viable after 10,000 to 50,000 years is more questionable," microbiologist Purificación López-García of the French National Center for Scientific Research told National Geographic. "Contamination during drilling with microorganisms attached to the surface of these crystals or living in tiny fractures constitutes a very serious risk."

But if Boston and her crew are correct, microbial life on Earth can endure much more than scientists previously thought possible. And this means that perhaps life off Earth is hardier than they thought, too.

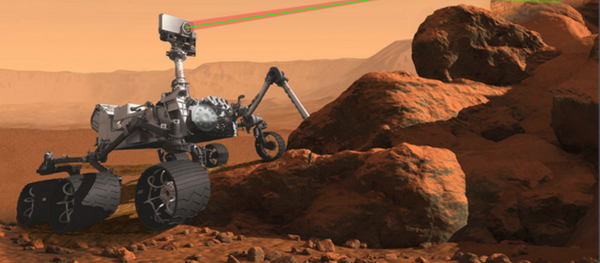

NASA goes to great lengths to sterilize spacecraft its spacecraft, Boston said, but with life proving to be much more stubborn than we delicate humans assume, the risk of bringing an invasive new creature into space, or indeed carrying one back, shouldn't be underestimated.

"The astrobiological link is obvious in that any extremophile system that we're studying allows us to push the envelope of life further on Earth, and we add it to this atlas of possibilities that we can apply to different planetary settings," she told reporters after announcing her findings, the Christian Science Monitor reports.

"How do we ensure that life-detection missions are going to detect true Mars life or life from icy worlds rather than our life? Aspects of my work illustrate the extreme toughness of life on Earth and the restrictions that places on us."

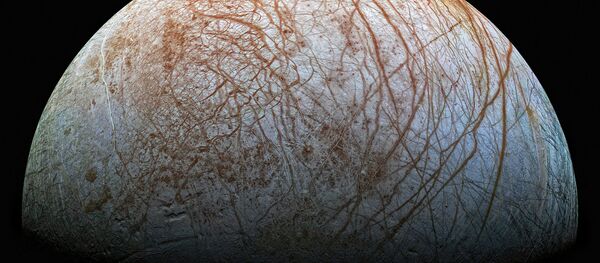

NASA is planning to bring back rock and ice samples from Jupiter's moon Europa, which has a salty ocean beneath its crust, and while once it was thought that no microbes could possibly survive a space journey, that has been shown not to be the case.

John Rummel of the Seti Institute in California said, "If we bring samples back from either Europa or Mars, we will contain them until hazard testing demonstrates that there is no danger and no life, or continue the containment indefinitely while we study the material," according to the Telegraph.