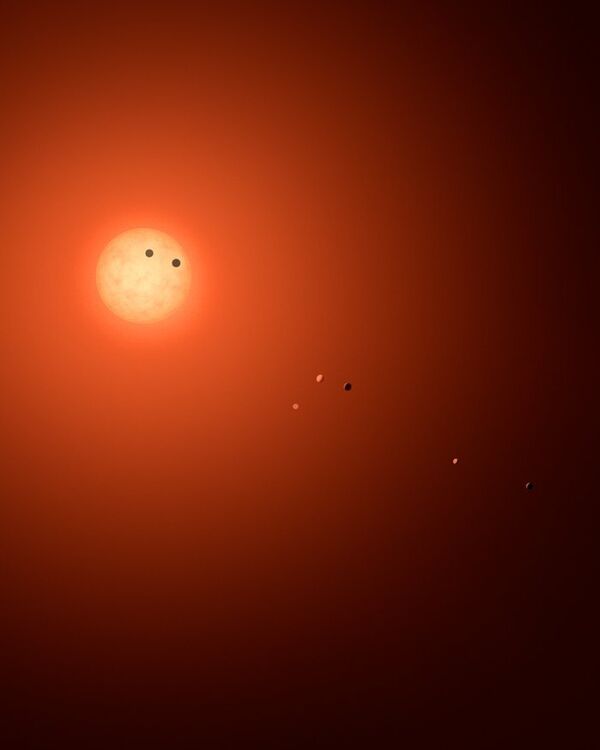

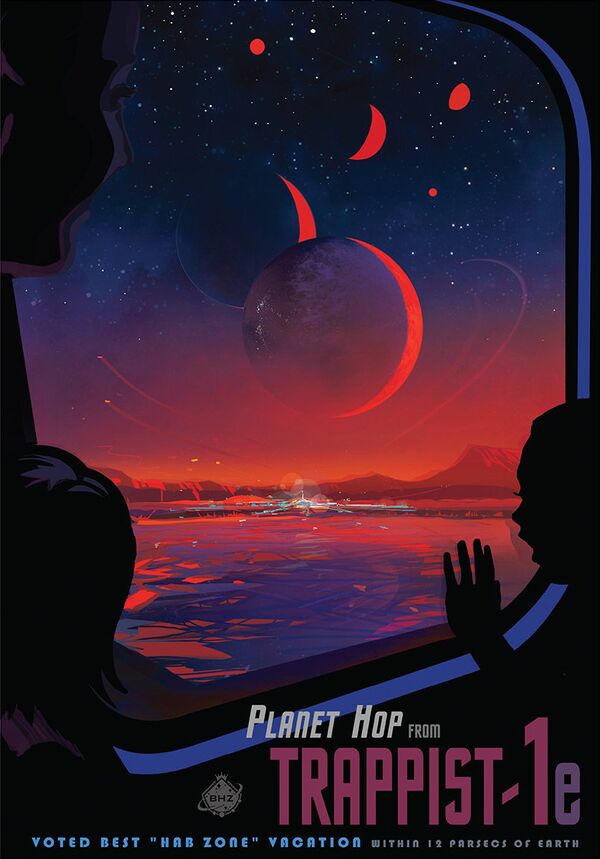

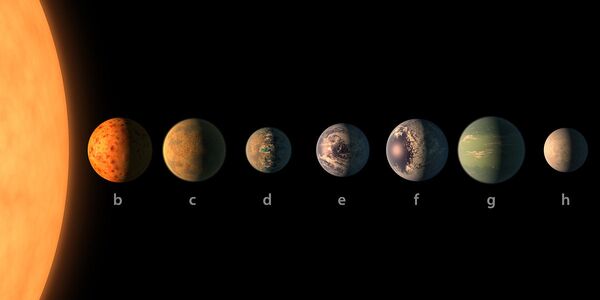

Three of the seven planets discovered were in TRAPPIST-1's "habitable" zone, meaning it would be easy for liquid water to develop on those planets, under the right atmospheric conditions. But the other four might still have water if their atmospheres are thick enough to trap heat in the same way Venus's atmosphere does.

TRAPPIST-1 was first discovered by Belgian astronomers in late 2015 using the Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope (TRAPPIST) in Chile. It caught the attention of NASA, who teamed up with a Belgian team out of the University of Liège to more closely study the ultracool dwarf star using the American Spitzer Space Telescope.

What they found was astonishing. "The discovery sets a new record for greatest number of habitable-zone planets found around a single star outside our solar system," wrote NASA in a news release. "All of these seven planets could have liquid water – key to life as we know it – under the right atmospheric conditions, but the chances are highest with the three in the habitable zone."

"The planets are all close to each other and very close to the star, which is very reminiscent of the moons around Jupiter," Belgian team lead Michaël Gillon said. "Still, the star is so small and cold that the seven planets are temperate, which means that they could have some liquid water — and maybe life, by extension — on the surface."

Gillon explained that never before has a system with three planets in its habitable zone been discovered. The Sun has two: Earth and Mars, plus the dwarf planet Ceres in the asteroid belt.

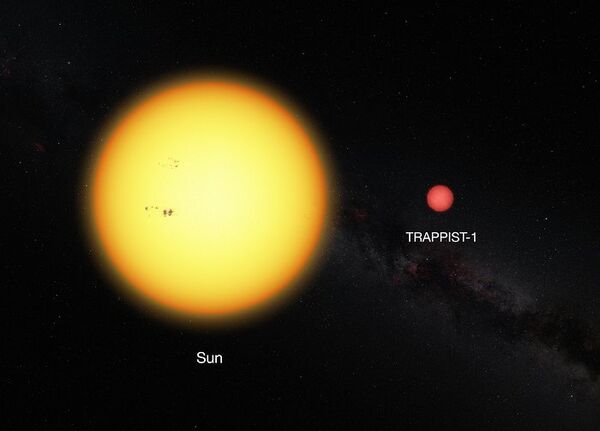

TRAPPIST-1 is 40 light-years from Earth, but its very low mass and heat make it hard to study. It is only 8 percent as massive as the Sun and just 500 million years old, an infant by stellar standards.

But as telescopes improve, TRAPPIST-1's dimness actually worked to astronomer's advantage. One of the central issues when hunting for exoplanets is that their own reflected light is often drowned out by the much brighter light of their parent stars.

Spitzer is an infrared telescope, and it observed TRAPPIST-1 for over 500 hours to confirm the seven planets. "This is the most exciting result I have seen in the 14 years of Spitzer operations," said Sean Carey, manager of NASA's Spitzer Science Center.

Spitzer, as well as the Hubble Space Telescope, have begun their hunt to identify the gases necessary for life, such as oxygen and methane, on the seven planets. NASA's bleeding-edge James Webb Space Telescope, to be launched in October 2018, will make this search far easier.

"The James Webb Space Telescope, Hubble's successor, will have the possibility to detect the signature of ozone if this molecule is present in the atmosphere of one of these planets," said study co-author Professor Brice-Olivier Demory with the University of Bern in Switzerland. "This could be an indicator for biological activity on the planet."

Demory added that the only way to know for sure if there is life on a distant planet would be to directly communicate with or observe it. When Earth was 500 million years old, life was extremely simplistic, if it existed at all. Even if one or more of TRAPPIST-1's planets has organics, they are unlikely to be complex.

Still, the find is exciting. NASA has identified 3,449 exoplanets, almost all of them in recent years. If life arose quickly on a young Earth, it is likely that at least a few of those uncovered by human space agencies also have organisms present.

"Could any of the [TRAPPIST-1] planets harbour life? We simply do not know," wrote Ignas Snellen, a Dutch astronomer with Leiden Observatory, in a comment on the original paper. "But one thing is certain: in a few billion years, when the Sun has run out of fuel and the Solar System has ceased to exist, TRAPPIST-1 will still be only an infant star. It burns hydrogen so slowly that it will live for another 10 trillion years… which is arguably enough time for life to evolve."