Like stars, planets form from massive clouds of dust and gas. But why these dust clouds tend to converge into one body is a question that the astronomical community has struggled to answer. The process of tiny grains of dust aggregating into pebble-sized pieces is well-understood, as is the process of asteroid-sized "planetesimals" becoming planetary cores.

It is the intermediate step, in which pebbles become kilometer-sized chunks, that science is shaky on. Scientists have not been able to satisfactorily explain how pieces of that size could aggregate, as they faced two major obstacles: pebbles being pulled into the young star's gravity and being consumed, or pebbles striking one another at high speeds and shattering, rather than combining.

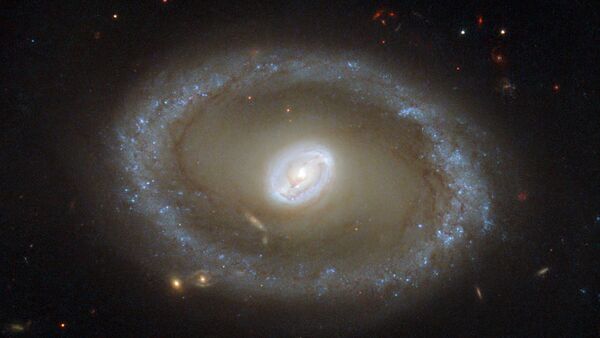

But an RAS simulation of a young solar system showed that the pebble-sized fragments come together to form "dust-traps." Forming in high-pressure regions, dust-traps are said to occur where movement is slowed. Dust-traps form much more commonly than previously believed, according to the simulation.

The effect relies on a known phenomenon called "aerodynamic drag back-reaction," which, in layman's terms, is when the congregating dust forces the gas lying between particles out from the clump of solid matter. The gas then forms a high-pressure region where these dust-trap clumps form into larger, and larger, planetesimals.

The simulation showed that aerodynamic drag back-reaction, previously thought to be a negligible phenomenon, is far more prevalent than previously believed.

For most of the history of modern human astronomy, it was believed that a majority of stars have few, if any, planets, and that our Sun is an exception. However, recent improvements in telescopes have proven our galaxy to be far more planet-rich than previously believed.

"Until now we have struggled to explain how pebbles can come together to form planets, and yet we've now discovered huge numbers of planets in orbit around other stars," said study lead Dr Jean-Francois Gonzalez, of the Centre de Recherche Astrophysique de Lyon, in France. "That set us thinking about how to solve this mystery."

"We were thrilled to discover that, with the right ingredients in place, dust traps can form spontaneously, in a wide range of environments. This is a simple and robust solution to a long standing problem in planet formation," added Gonzalez.

Telescopes, like the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, have identified dust-traps around young stars, giving credence to the findings of Gonzalez's team.