From 1976-2003, anyone with money to burn could fly aboard a supersonic Concorde jet. The astonishing plane flew at over 1,300 miles per hour, allowing it to cross the Atlantic in just 3.5 hours, half that of an ordinary passenger airliner.

But the program was plagued with problems. Tickets were outrageously expensive, about $15,400 for a round trip in 2017 money. The plane's high flight pattern made it significantly more dangerous to the ozone layer than a regular jet, and it could only carry a little over a hundred passengers, requiring specially-trained pilots and mechanics.

Perhaps most damningly, it could not fly over land, as it caused so much noise, due to its sonic boom. When an object exceeds the speed of sound it creates waves of pressure in its wake that compress against one another and form an explosive shock wave behind it. The sonic booms caused by the Concorde rattled buildings and created severe noise pollution.

Declines in commercial aviation after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, and a crash that killed 113 passengers and crew in 2003, heralded the end of the Concorde program, and with it, commercial supersonic flight.

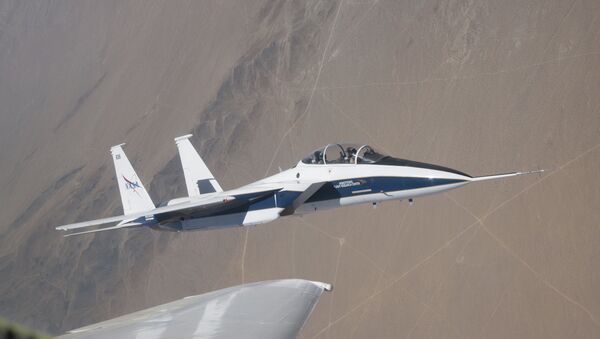

But NASA wants to bring supersonics back, and they intend to tackle the problems one at a time. Firstly, the sonic boom. The Concorde had "double delta" triangular wings, which did little to minimize noise. The new supersonics being tested by NASA instead have more traditional swept wings, as you would see on any typical large aircraft.

Swept wings minimize sonic boom, but in the past suffered too much from air resistance to be used at supersonic speeds. A plane moving faster than sound must burn more fuel to overcome intense air-friction drag.

To address this, NASA is experimenting with swept-wing laminar flow technology. In effect, NASA's wing design creates a layer of smooth air, known as a boundary layer, that protects the wing from drag. Formulating the perfect wing shape and construction to maximize laminar flow and minimize drag is something NASA has been working on since the 1980s.

"Supersonic laminar flow is something of an elusive holy grail for aerodynamicists," stated project manager Peter Coen. "This test, while still exploring fundamentals, is an important step toward achieving CST's fuel efficiency goals for quiet supersonic overland airliners."