47 Tucanae X9 is a binary star system 14,800 light-years from Earth. Or at least, astronomers identified it as a binary star system when it was discovered back in 1989. In 2015, NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory learned that one of the stars was in fact a black hole, slowly eating its mate.

"For a long time, it was thought that X9 is made up of a white dwarf pulling matter from a low mass Sun-like star," said researcher Arash Bahramian. But analysis from Chandra, which has been the source of most x-ray data since its 1999 launch, has debunked that long-standing hypothesis.

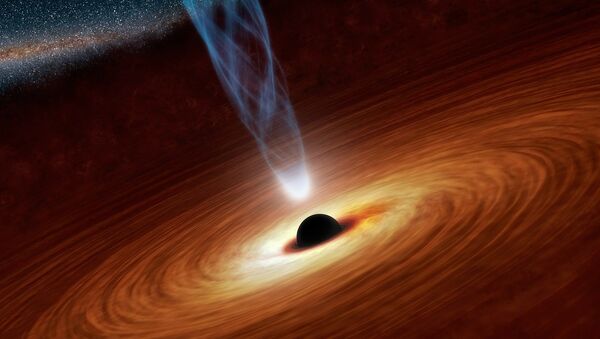

Objects orbiting black holes can reach incredible speeds. Black holes have enormous gravity and impart some angular momentum to things caught in their gravitational fields. The closer an object gets to the black hole, the faster it moves – and the more likely it is to fall into the abyss and be torn to shreds by the event horizon.

X9's star, a super dense white dwarf with intense gravity in its own right, completes an orbit around its black hole every half hour from a distance of about 600,000 miles. This makes it the closest star/black hole combo ever discovered. The previous record holder, MAXI J1659-152, has an orbit almost five times as long, which suggests an orbit three times as large.

By comparison, the moon speeds around Earth at about 2,300 mph, while the Earth moves around the sun at 67,000 mph. The sun hurtles through the Milky Way at 483,000 mph. The fastest object ever observed in our solar system, a comet that fell into the sun in 2016, was moving at 1.3 million mph.

"We think the star may have been losing gas to the black hole for tens of millions of years and by now has now lost the majority of its mass," said James Miller-Jones of Curtin University and the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research.

Although the X9 black hole is slowly eating the star, it may never consume it entirely. In fact, researchers believe it possible for the white dwarf to escape fully from the black hole's orbit.

"Eventually so much matter may be pulled away from the white dwarf that it ends up only having the mass of a planet," said researcher Craig Heinke. "If it keeps losing mass, the white dwarf may completely evaporate."

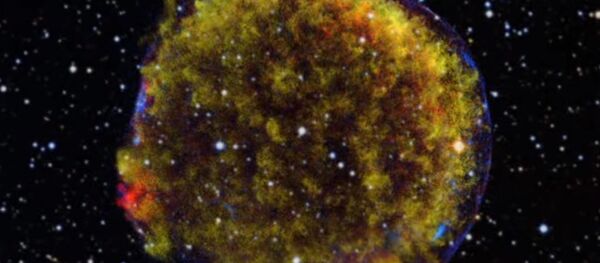

"Finding these rare black holes is important as they are not only the end-points of massive stars, produced in supernova explosions, they also continue to play a role in the evolution of other stars after their deaths," said Professor Geraint Lewis from the University of Sydney, who was not part of the study.