In Germany, the ashes of the dead are usually buried in graves. Artist Heide Hatry however, began thinking of alternative ways that could help the mourning process during a trip to the US, where she peered into the urn of a friend that contained the remains of his wife.

"That experience had touched me deeply, and maybe because of that I had the sudden idea that I needed to make portraits out of my friend's and my father's ashes. But even as the idea came to me, in a sort of revelation, I already started to feel a calm arise within me," Ms. Hatry told Sputnik.

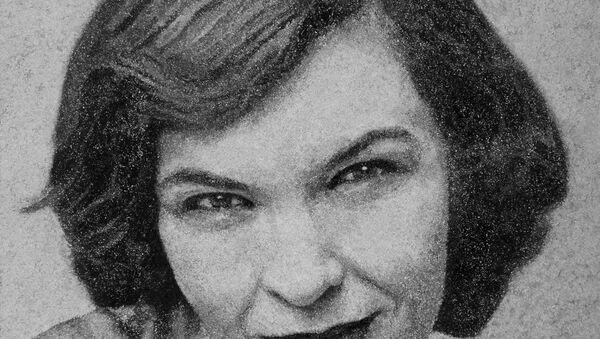

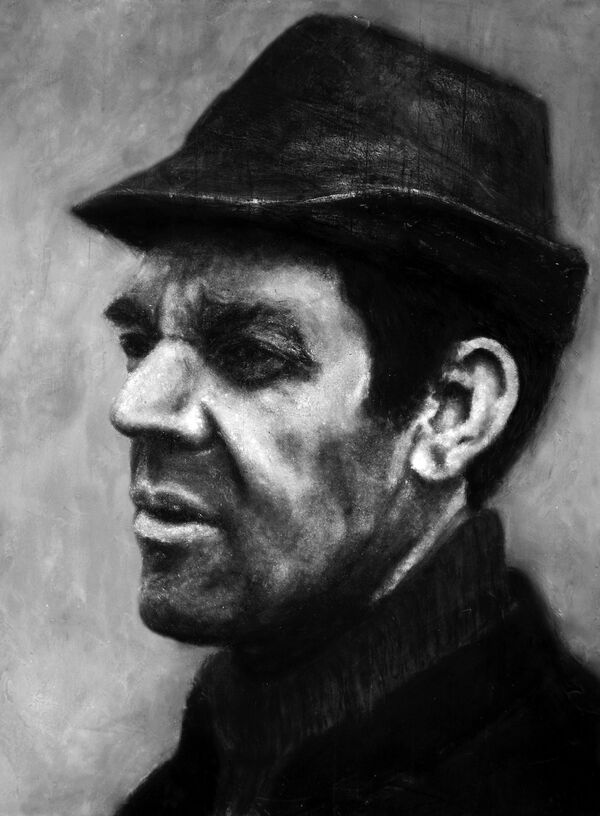

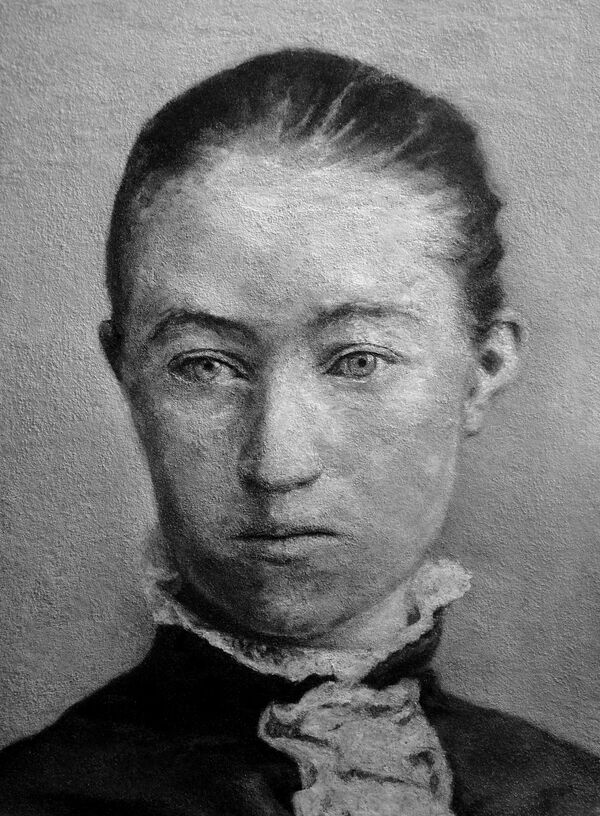

The process of creating images with ashes took several months to master, as Hatry used the remains of unclaimed animal ashes for her practice portraits. She also had to find a way to color the ashes, which are only a shade of grey as they are pure bone.

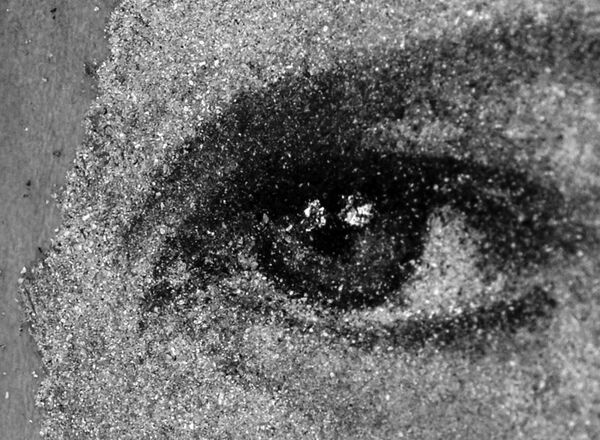

Ms. Hatry said she used "white marble dust (as a symbol of death) and black birch coal (as a symbol of life) to get a palette ranging over different shades of grey."

"I am hunched over the work sometimes for weeks, applying these microscopic fragments with the tip of a scalpel. It is like reconstructing a broken image," she added.

Ms. Hatry, who is showcasing some of her portraits as part of an exhibition, Icons in Ash: Cremation Portraits, at the Ubu Gallery in New York until May of this year, said her work has been largely well-received by the public and grieving families have approached her to make portraits of their loved ones.

"More specifically, though, a lot of people feel something like despair when the people they loved die, like a part of them has died, too, or that they have suffered a horrible trauma," the artist told Sputnik.

"Knowing that the person is actually right there in front of you, as if seeing you as you look at him or her, has a powerful effect. The friends for whom I made a portrait all told me that they also sometimes talk to their beloved one."

Although Ms. Hatry maintains that the zeitgeist has received the idea favorably, she gave up on the project for several years amid fears that people would be reminded of "the legacy of the Nazi crematoriums."

She admitted she was "extremely troubled" that the project would cause more pain than solace, but after much soul-searching, she came to the conclusion that the portraits would be an "act of reverence" for dead loved ones.

"It was only after I researched specifically what the Nazis were doing and what they intended, that I could resume it, because I knew that my purpose was exactly the opposite: where they wanted to obliterate a whole people and make it as though they had never existed, to destroy them, and eliminate every trace of them, I am remembering, preserving, honoring, and making present what is lost to us," Ms. Hatry told Sputnik.