This week, Ukrainian media reported that Warsaw is in the process of reviewing its former immigration policy, including its position vis-à-vis Ukrainian economic migrants.

Saying that the 2012 document on migration policy "did not meet the challenges facing [Poland]," Internal Affairs Minister Mariusz Blaszczak explained that these challenges include both the broader EU-wide refugee crisis, and the issue of Ukrainian economic migrants to Poland. Accordingly, the government has annulled the 2012 document, on the recommendation of the Ministry.

Warsaw will now devise a new strategy – one that takes into account both of these factors. The Ministry for Internal Affairs has advised tougher monitoring of migration processes, long-term strategizing on integration or assimilation, and efforts to ensure security against the threats of crime and terrorism.

Warsaw and Brussels have had a very public falling out over the issue of Middle Eastern and North African refugees, with Poland along with many other Eastern European countries simply refusing to accept EU quotas, aimed at distributing the migrants across Europe in a more even manner. At the same time, since the start of the crisis in Ukraine in 2014, Poland has seen a massive spike in migration from Ukraine. It is estimated that there are up to half a million Ukrainians living and working in Poland, with up to a million to a million and a half more Ukrainians working in the country temporarily.

Apples & Oranges

In a special analysis on the topic, Ukrainian Political observer and RIA Novosti contributor Rostislav Ishchenko laid out why Ukrainian migrants pose a threat to Poland's political stability, and explained why Warsaw's efforts in relation to Ukrainian migrants are about to get a whole lot tougher.

For starters, the expert stressed that the European migrant crisis isn't as much of a threat to Poland (and other Eastern European countries) as it is to Western Europe. The refugees from the Middle East and North Africa aren't particularly eager to settle down in Eastern Europe, owing to the comparatively poorer economic opportunities.

Meanwhile, the expert noted, with the EU set to cut off billions of euros in development grants to Eastern Europe, it is losing a once significant lever of influence on policy anyway.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, "along its western border, Poland has as neighbors countries with stable state systems capable of maintaining order on their territories; therefore, the storming of the Polish-German border by thousands of refugees, for example, cannot be expected in the near future."

Unfortunately, Ishchenko noted, Poland faces "quite a different situation" on its eastern border with Ukraine. "According to official figures, the number of economic migrants from Ukraine already tops half a million people." In reality, the analyst noted, this figure may jump as much as 300-400%, taking into account illegal immigrants, as well as those working in the country on a rotational basis. In that case, there may now be between 1.5 and 2 million Ukrainians temporarily or permanently residing in the country.

"For Poland, with its population of 38 million, that's significant," the analyst stressed. "All the more so because hundreds of thousands of 'Polish plumbers'," (i.e. the derogatory Western European epithet for Polish skilled laborers to countries like France and the UK) are now being squeezed out by those very same Asian and African migrants in the countries of Western Europe."

In other words, the country is facing a potentially tense situation where Ukrainians are holding many of the same jobs in Poland which Poles have recently lost in the West.

Warsaw, according to the analyst, has already attempted to tighten its policy, forcing companies to hire migrant workers at the same wages as local citizens; this has made it possible for employers to save on wages only by using illegals – who can easily be deported if necessary.

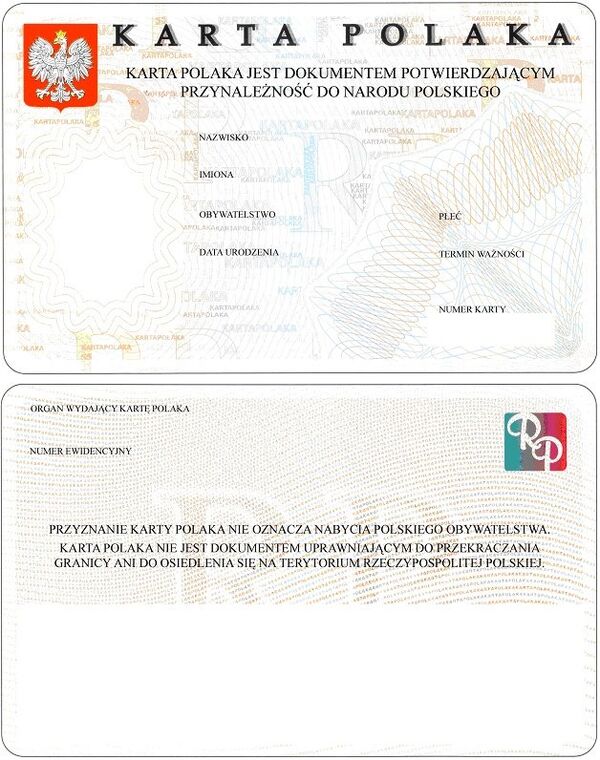

"However, even all these measures cannot guarantee Poland a reliable barrier against migration from Ukraine," the expert noted. For nearly 20 years, Warsaw has been granting western Ukrainians the so-called Karta Polaka (literally 'Pole's Card'), allowing Ukrainians to legally stay and work in Poland and even qualify for Polish citizenship. Millions of Ukrainians have received the card, with upwards of 100% of Ukrainians from some border regions being granted the card.

"And while one can cancel the benefits associated with the Karta Polaka, or annul it as a document, one cannot change the economic priorities and ties of tens of millions of people accustomed to earning a living in Poland," Ishchenko stressed. "This is particularly true in a situation where Ukraine's economic collapse is permanent, even stabilization of the situation, not to mention any sort of improvement, not expected in the near future."

Accordingly, the observer suggested that pending any impending changes in the Polish labor market, or to Polish immigration law, these same Ukrainians will not be able to find work at home, nor in other Western European countries.

Meanwhile, the analyst warned, with Ukraine inching closer and closer to the status of a failed state, there are no longer any guarantees that Kiev will be able to ensure reliable border control on its western frontier. In this situation, he stressed, "a repeat on the Polish-Ukrainian border of last year's situation with crowds of migrants storming Europe's southern borders…is not only likely, but inevitable."

The only difference, Ishchenko noted, is that the crowds of refugees, from the Middle East anyway, were controlled by Turkey," with an EU agreement with that country helping to stem the flow. The same cannot be said in Ukraine's case. "No one will control the flow Ukrainian migrants; furthermore, there is a high probability that many of them may be armed."

"In such a situation, administrative and policing measures aimed at regulating migration and protecting the border will not be enough; at the same time, European rules do not allow for the use of the army to protect borders…Warsaw is likely to find itself in a situation where its policing forces are physically unable to keep crowds of migrants from breaking through the border."

"In order to achieve her goal, [Tymoshenko] will simultaneously promise everything to everyone– a visa free regime to Europe for Ukrainians, peace for the pacifists, victory in the civil war for the militarists, the glorification of Bandera to Banderites, the elimination of Bandera's image to the Poles, etc."

Unfortunately, Ishchenko noted, Tymoshenko's real opportunities for stabilizing the situation in the country are even more modest than Poroshenko's, particularly in light of the private armies which have been established by the country's politicians and oligarchs, who are not prepared to share their wealth and resources with any central authorities.

Accordingly, the analyst explained, "the only real way for Poland to more or less reliably protect its borders from crowds of Ukrainian refugees will be to create a buffer zone." In this situation, Poland would facilitate the creation of entities on its eastern borders similar to those that have appeared in eastern Ukraine on the border with Russia.

The problem for Warsaw, in Ishchenko's view, is that western Ukrainians don't exactly have an affinity for Poland, particularly in light of their difficult historical relationship. "Their population is not as friendly toward Poland as that of the Donbass is toward Russia. Undoubtedly, the creation of such protectorates will require substantial material investments from Warsaw, if they want to ensure the stability of the local regimes. These funds can be obtained partly from the EU budget – after all, it's not just a question of Poland's borders, but those of the EU."

Ultimately, the observer stressed that these buffer zones may be Warsaw's only real option. Otherwise, "maintaining the current state border regime with Ukraine may raise questions about the survival of Poland itself, and in the near future," Ishchenko concluded.