Researchers have hitherto been prevented from creating full-size tissues for treating disease and traumatic injuries by not being able to establish a vascular system capable of delivering blood deep into the developing tissue. In essence, no bioengineering technique, including 3D printing, has been able to manufacture the branching network of blood vessels down to the capillary scale required to deliver the oxygen, nutrients and essential molecules required for proper tissue growth.

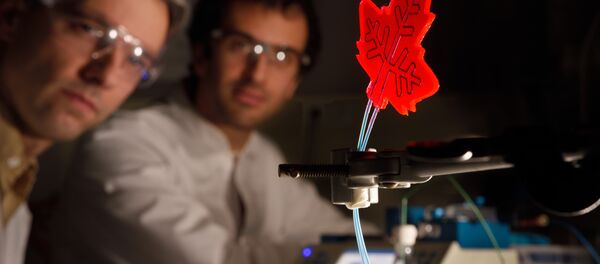

The WPI researchers turned to plants in hope of a solution. Detailing their work in a paper, Crossing kingdoms: Using decelluralized plants as perfusable tissue engineering scaffolds, the team document a series of experiments in which they flowed fluids and microbeads similar in size to human blood cells through spinach's vasculature, seeding the leaf's veins with human cells that typically line blood vessels.

When the plant cells were washed away, what remained was a framework made primarily of cellulose, a natural substance not harmful to people. Cellulose is biocompatible, and has previously been used in a wide variety of regenerative medicine applications, such as cartilage tissue engineering, bone tissue engineering, and wound healing.

WPI team grows heart tissue on spinach leaves https://t.co/4hCslNJc4C

— Science (@scienmag) March 22, 2017

In addition to spinach leaves, the team successfully removed cells from parsley, Artemesia annua (sweet wormwood), and peanut hairy roots. They expect the technique will work with many plant species that could be adapted for specialized tissue regeneration studies.

Spinach leaves might be better suited for a highly-vascularized tissue, such as cardiac tissue, whereas the cylindrical hollow structure of the stem of jewelweed might better suit arterial graft, and the vascular columns of wood might be useful in bone engineering due to their relative strength and geometries.

Using plants as the basis for tissue engineering also has economic and environmental benefits.

By exploiting the benign chemistry of plant tissue scaffolds, the scientists believe it may be possible to address the many limitations and high costs of synthetic, complex composite materials.

The team believes their findings open the door to using multiple spinach leaves to grow layers of healthy heart muscle to treat heart attack patients, and other plants to engineer tissue.

"We have a lot more work to do, but so far this is very promising. Adapting abundant plants that farmers have been cultivating for thousands of years for use in tissue engineering could solve a host of problems limiting the field," said Dr. Glenn Gaudette, Professor of Biomedical Engineering at WPI.

The research will continue, with studies to optimize decellularization processes and further characterize how various human cell types grow while they are attached to, and are potentially nourished by, plants.