MOSCOW (Sputnik) — On January 1, 1973, the United Kingdom joined the European Economic Community. In 1992, the country signed the Maastricht Treaty and became a member of the European Union.

From its first years in the bloc, the United Kingdom sought to maintain the maximum possible independence in important economic and political issues. Particularly, the country did not join the union’s major integration projects, including the Schengen Agreement (1995) of visa-free travel across common borders or common European currency, the euro (1999).

At the EU Summit in March 2012, London refused to sign the Stability and Growth Pact lobbied by Berlin and Paris that introduced tough fiscal discipline.

In 2011, during the economic crisis the public in Britain expressed increasing discontent with the country’s membership of the European Union. Conservative parliament member David Nuttall proposed a referendum on the country’s EU membership. A referendum petition was signed by over 100,000 British citizens.

On October 25, 2011, British members of parliament voted against holding a referendum with a majority vote (483 of 650). The vote was preceded by five hours of debate. In his opening remarks, then UK Prime Minister David Cameron asked parliament members to vote against holding the referendum and stressed that the timing was not right as Europe was in the middle of a crisis.

In January 2013, Cameron announced in an election campaign speech that the United Kingdom could hold an EU exit referendum at the end of the decade if the Conservative Party headed by him won the 2015 election.

In the May 7, 2015 general elections, the Conservatives received 36.9 percent of the vote, against 30.4 percent for the Labour Party, ensuring an absolute majority in the House of Commons. Cameron formed a one-party government.

On May 28, 2015, the UK government submitted a bill to the parliament on Britain’s exit referendum from the European Union. The referendum question was "Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union?" The referendum was scheduled for a date no later than December 31, 2017.

On November 10, 2015, Cameron announced the official start of a campaign for changes in the membership terms for the United Kingdom with the EU bloc. He sent a letter to the European Council with London’s demands for the European Union.

The demands were divided into four categories: reducing the immigrant flow from the bloc to the United Kingdom; increasing competitiveness; strengthening Britain’s sovereignty, specifically, withdrawal from the obligation to work toward an "ever closer union;" changes in the currency issues.

Cameron promised he would vote for Brexit in the referendum if said conditions were not satisfied.

From November 2015, when Cameron presented the demands, the agencies of the European Council and the European Commission conducted intense negotiations with London to agree on the details of a possible deal.

On February 19, 2016, it was announced that after two days of debate, the EU leaders agreed on new terms for Britain to remain in the union. With these terms granted, the UK prime minister would vote to remain in the bloc in the upcoming referendum. The EU members approved a document that was to become effective on the day the British government notified the Council of the European Union secretary-general of the UK decision to stay, after the referendum.

Among the agreements reached at the EU summit was protection for the UK welfare system for seven years without extension, and a four-year "probation period" during which newly arrived migrants would not be entitled to social benefits. Another important issue was to release the United Kingdom from the obligation to an "ever closer union" that requires integration of the countries in the European Union. The third key point was that Britain will never join the euro zone.

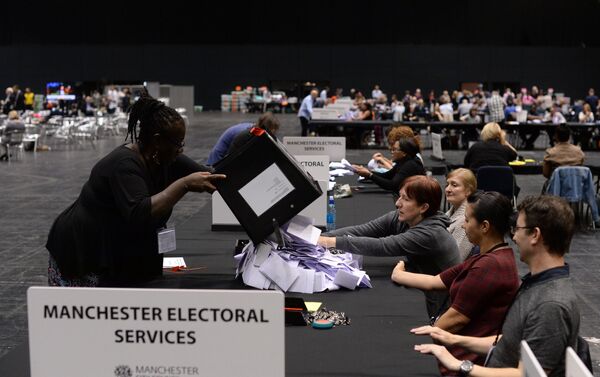

On June 23, 2016, the Britain held the referendum on the country’s exit from the EU bloc initiated by Cameron. Fifty-two percent voted to leave the bloc and 48 percent voted to remain. On June 24, 2016, Cameron announced his resignation following the referendum on the UK membership of the bloc. Cameron, who spoke out against Brexit, intended to keep his post regardless of the vote but changed his decision.

On July 13, 2016, Theresa May took charge of the UK government.

In August 2016, British media suggested that May could initiate an exit from the European Union (as described in Article 50 of the Treaty of Lisbon) without parliamentary debate and voting.

The debates were requested by some opposition members in the House of Commons. They hoped to block by parliament vote the decision to leave the union made during the referendum.

The prime minister’s spokesperson said that consultations regarding the bill were not necessary.

May’s reluctance to bring EU exit legislative issues to a vote resulted in a political confrontation between the government and the parliament.

A group of politicians led by finance expert Gina Miller sued the government and claimed in the lawsuit that May’s cabinet had no right to launch Brexit without the clear consent of the parliament.

On November 3, 2016, the High Court of London ruled that the government required the parliament’s approval to initiate Brexit. The judge rejected the government’s argument that there was no need for a parliament vote because the majority of the public had already expressed its will in the June 23 referendum and had voted to leave. The government announced it would appeal the verdict.

On December 6, the government gave in to the insistent Labour Party and agreed to publish its exit plan before the launch of Brexit and urged the parliament not to create obstacles to the process. The cabinet of ministers was forced to compromise after it became clear that some 40 Conservative members of parliament intended to join the opposition parties and protest the government’s unwillingness to publish its Brexit plans details.

On January 17, 2017, May presented the Brexit plan in a special speech. According to the plan, Britain would not only leave the EU bloc but also the European single market and the EU Customs Union.

On January 24, the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom ruled that the government could not refer to Article 50 of the Treaty of Lisbon before the parliament approved the respective bill.

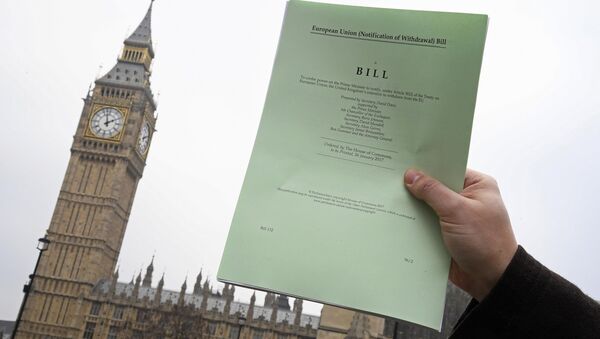

The government complied with the court's ruling and, on January 26 submitted a bill on half a page to the parliament. The bill stated that the prime minister could notify Brussels of the UK intention to leave the bloc after the approval of the bill by the House of Commons and the House of Lords and the consent of Queen Elizabeth II.

On January 31, the House of Commons started a discussion on the bill, thus launching a process of the country’s exit from the European Union.

On February 2, the UK government published the so-called White Paper setting forth its plan to exit from the European Union. The document outlined London’s stance on cooperation in politics and the economy and covered the issues of immigration.

On February 8, the House of Commons approved the exit bill in the third reading. The third reading vote took place after a three-day discussion within committees when legislators supporting Britain’s EU membership tried to change the document in order to give the parliament more influence in Brexit. The majority of changes were rejected.

On March 14, the House of Lords approved the bill on the launch of Brexit in its original wording without amendments. Initially, the lords lobbied for two amendments. They requested that the government guarantee permanent resident status for EU citizens living in Britain and they wanted to legislate the prime minister’s promise to present the final agreements with the bloc to the parliament. Later, the lords decided to drop their requests.

On March 16, Queen Elizabeth II approved the exit bill and the document became effective.

On March 20, it was reported that May would begin the Brexit process on March 29.

It was estimated that Brexit would cost the United Kingdom 50-60 billion euros ($54-65 billion) that London would have to pay to the European Union under the existing agreements. The estimate includes Britain’s long-term obligations.