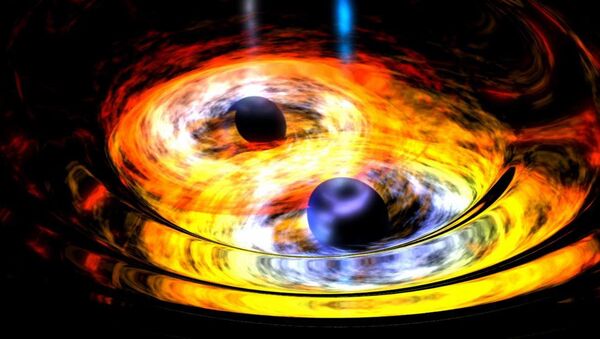

It's believed that around 1.3 billion light years away from Earth, two black holes cataclysmically collided, releasing energy — gravitational waves — which undulates across the universe like ripples in a pool.

Gravitational waves had long been speculated upon, and were a major prediction of Albert Einstein's 1915 general theory of relativity, but the existence of these wrinkles in the fabric of space-time was only confirmed in September 2015.

Astrophysicists at @unibirmingham have made progress on unravelling the puzzle of merging black holes @eps_unibham https://t.co/rq2voBF8lT pic.twitter.com/fJ9xSPkYHs

— UniBirmingham News (@news_ub) April 5, 2017

The discovery, says Professor Ilya Mandel of Birmingham University's School of Physics and Astronomy, opened "an unprecedented new window" into the cosmos.

However, the manner in which such pairs of merging black holes form remained elusive. In order to do so, black holes must start out very close together by astronomical standards, no more than around a fifth of the distance between the Earth and the Sun. Only stars with very large masses can become black holes — and during the course of their lives, these stars expand to become even larger — raising questions as to how more than one large binary star can fit within a single, small orbit.

Paper by @simon4nine @cplberry & Mandel on using #GravitationalWaves to understand the origin of binary black holes https://t.co/Ps9FXcwgZG pic.twitter.com/AZ577LAM3h

— BIGWaves (@UoBIGWaves) March 21, 2017

A team of Birmingham University astrophysicists set out to unravel the mystery. The group used a model called COMPAS (Compact Object Mergers: Population Astrophysics and Statistics), which allowed them to pursue a kind of "paleontology" for gravitational waves.

"A palaeontologist, who has never seen a living dinosaur, can figure out how the dinosaur looked and lived from its skeletal remains. In a similar way, we can analyze the mergers of black holes, and use these observations to figure out how those stars interacted during their brief but intense lives," Professor Mandel told Sputnik.

The researchers started by analyzing the three gravitational waves detected in September 2015, and attempting to see if all three collisions evolved in the same way. Professor Mandel explains they found even two widely separated "progenitor" stars can interact when expanding, engaging in several episodes of mass transfer.

"This results in a highly unstable event that envelops both stellar cores in a dense cloud of hydrogen gas, and ejecting this gas from the system takes energy away from their orbit. This brings the two stars close together enough for gravitational-wave emissions to occur," Professor Mandel continued.

It takes at least a few million years to form two black holes, and further before they're in a position to merge into a single, larger black hole — but the merger itself can be swift and brutal.

Want to update your #GravitationalWaves knowledge? We have a focus issue that could help! https://t.co/qLTKwquWzE (image credit @NASA) pic.twitter.com/Il2JTYRks3

— Class. Quantum Grav. (@CQGplus) March 30, 2017

COMPAS has also helped the researchers understand the typical properties of binary stars that can go on to form such pairs of merging black holes, and the environments in which this is possible — for example, the team found a merger of two black holes with significantly unequal masses would be a strong indication some stars are formed almost entirely from hydrogen and helium, with other elements contributing fewer than 0.1 percent of stellar matter.

"This discovery allows us to look back to the distant past, and start to probe the processes that formed the early universe, and the galaxies we see today. We look as far back to a million years after the Big Bang," Professor Mandel continued.

The team will continue to use COMPAS, in an attempt to gain greater understanding of how binary black holes may have formed, and how future observations could tell us even more about the most seismic events in the history of the universe.