As they lie in the ground, landmines leak minute quantities of explosive into the surrounding soil and water.

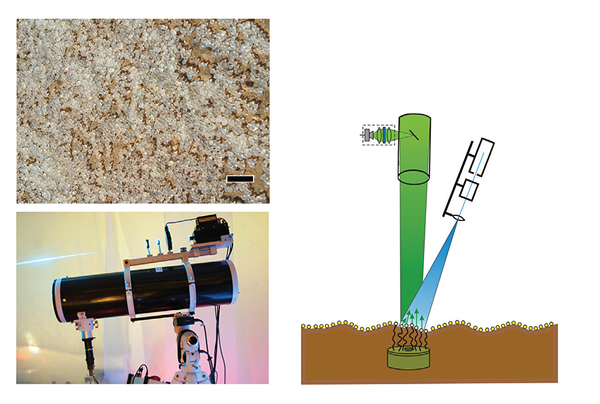

Using molecular engineering, the researchers modified bacteria to give off a fluorescent signal when they come into contact with the explosive. Enclosed in polymeric beads, the bacteria were scattered across a minefield.

The scientists then scanned the minefield with lasers, which were able to detect the fluorescent signals and hence the landmines.

"Our field data show that engineered biosensors may be useful in a landmine detection system," Prof. Shimshon Belkin, from the Hebrew University's Alexander Silberman Institute of Life Sciences, told Phys.org.

"For this to be possible, several challenges need to be overcome, such as enhancing the sensitivity and stability of the sensor bacteria, improving scanning speeds to cover large areas, and making the scanning apparatus more compact so it can be used on board a light unmanned aircraft or drone."

The latest research builds on previous advancements in the development of a less dangerous way of finding landmines. At present, their detection is carried out by human sappers using metal detectors and sometimes sniffer dogs.

Last year, researchers at the University of Bristol (UK) began developing drones that could fly over affected areas looking for damage caused by the leaking of landmine explosives.

According to the humanitarian relief agency CARE, there are an estimated 110 million anti-personnel mines buried in the ground across the world, intended to maim or kill humans. At least 70 people are killed or injured by landmines each day.