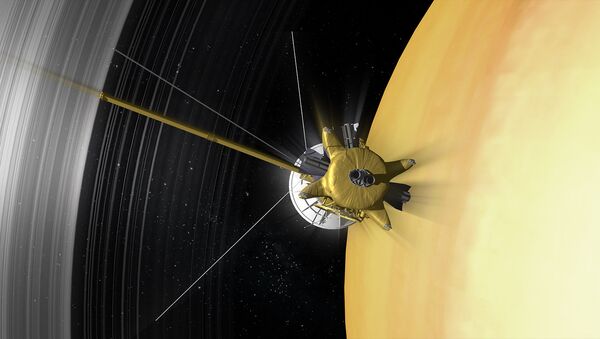

To accomplish this, Cassini has used Saturn's largest moon, Titan, as a slingshot to boost its speed, as it has nearly run out of fuel. It will make 22 "ring dives," where it dips in and out of the fringe of Saturn's atmosphere to take up-close ring photos and then beam them back to Earth.

The dives will occur weekly, and at its closest approach Cassini will be only 1,840 miles from Saturn's atmosphere.

The mission has placed Cassini on a "ballistic trajectory" that can end in only one way: the obliteration of the spacecraft. There's a good chance that the probe will be disabled during one of the ring dives, at which point it will have nowhere to go except to be sucked into Saturn's atmosphere.

"We're guaranteed to end up in Saturn's atmosphere in September," Scott Edgington, Cassini deputy project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), told Space.com. "If we get hit by a particle [during the first dive] that disables the spacecraft, we are still guaranteed to end up in Saturn."

Even if Cassini completes all 22 dives, it will have used up the last of its fuel in the process. Its final trick on September 15 will be to dive towards the gas giant, at which point Saturn's crushing atmosphere will utterly obliterate the spacecraft.

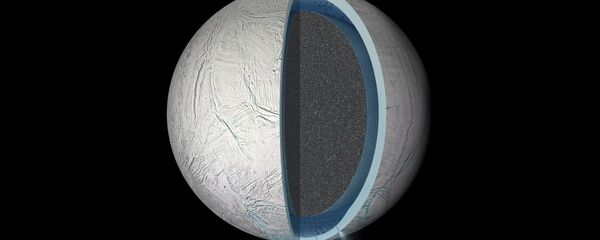

This will be done to prevent Earthly bacteria attached to Cassini from contaminating any of Saturn's moons or ring movements. "NASA has certain rules to follow about not contaminating any place that we think might be habitable," said Edgington.

NASA spacecraft are sterilized before they leave Earth, but some resilient bacteria can survive sterilization and 20 years in space. Although unlikely, NASA isn't taking the chance of contaminating one of Saturn's moons, like Enceladus, which the space agency recently announced may be able to support life.

"Something's going on in there! You have geologic activity, hot water chemistry going on, which is creating an environment for the molecules that life-forms might need," Edgington said. "So yes, we want to protect Enceladus. But we also want to protect Titan. Titan has been a keystone for the majority of our mission."

"We've only been at Saturn for what is, effectively, half a Saturn year, but [in that time], we're seeing all these detailed changes going on within that system." Cassini has observed enormous storms on Saturn and learned a great deal about the planet's many moons.

But the inner rings remain one of Saturn's – and the solar system's – biggest mysteries. Scientists still don't know if these rings formed along with the planet, or if they came into existence later on. "The Grand Finale" hopes to answer this question.

Cassini, named for the Italian astronomer who discovered four of Saturn's moons in the 17th century, launched in 1997 and in 2004 became the first human spacecraft to enter Saturn's orbit.