"I got to go back to Seagoville and see some of my old buddies," Brown told D Magazine. "They came in and told me, 'You won. Get your stuff ready,'" he said of his Monday release.

Formerly an "agitator" with hacktivist group Anonymous, Brown received a 63-month sentence in January 2015, after initially facing more than 100 years locked up.

Brown pleaded guilty to charges of threatening an FBI agent and obstruction of justice. At one point, the journalist faced 17 charges including hyperlinking to a document with stolen credit card information. Since his release in November, he lived at a halfway house before going into home confinement.

Brown was again detained on April 27 for allegedly failing to get BOP permission to speak to media outlets, something he said he was never told he needed to do. Brown was supposed to do an interview on the set with PBS — a government-funded broadcaster — the next day, and previously spoke with Vice News the week before.

Following his release from prison November 29 of last year, Brown gave his first exclusive interview to Eugene Puryear, host of By Any Means Necessary on Radio Sputnik.

On Sunday, Brown said that after 72 hours “in the hole,” he had not been given written proof detailing that he had committed an infraction of his parole terms. An infraction sheet is supposed to be provided within 24 hours, indicating a gross violation of due process. Why Brown is being denied normal treatment under the law, "is a question nobody seems to be able to answer," Jay Leiderman, a founding member of the Whistleblower Defense League, told Sputnik in an interview.

In a statement on Sunday, Brown said D Magazine “has been kind enough to enlist the services of David Siegal of the Haynes and Boone law firm.” One day later, a D Magazine article reported that “major credit for freeing Barrett goes to David M. Siegal.”

“The treatment of Barrett Brown by the Bureau of Prisons was unjustified and in violation of his First Amendment Speech Rights,” Siegal said in a statement. “Unfortunately, Barrett was forced to spend three days in a federal penitentiary when he should have been out living his life. We are happy we were able to work with Barrett and his family to achieve his return home today.”

According to Siegal, Brown has still not received an explanation as to why he was re-arrested. An inquiry sent to the BOP on Sunday by Sputnik asking to confirm or deny whether Brown had received an infraction sheet shed no further light on the situation: it has gone unanswered.

The BOP told Brown “out of the blue,” Leiderman explained to Sputnik, that he needed prior authorization before doing media interviews.

In a recorded conversation between Brown and the BOP, Brown asks the BOP to show where in their policy manual it states that Brown must get permission to do interviews. The issue with that is "it doesn't exist," Leiderman told Sputnik Monday evening. "They knew it didn't exist," he added.

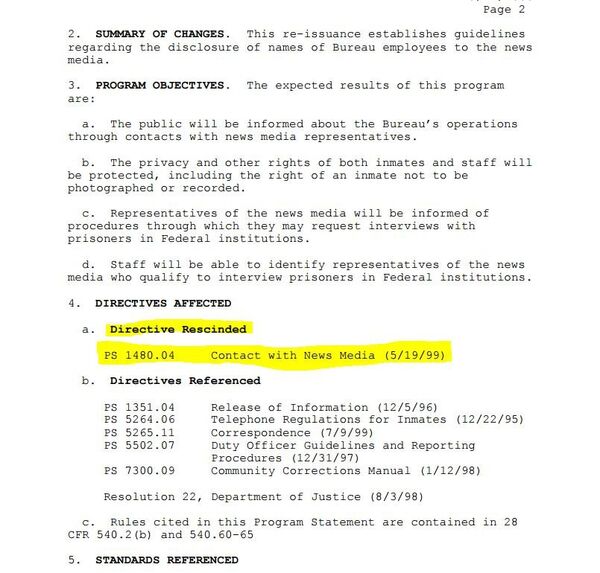

After a week of calling BOP "regional chieftain" Luz Lujan, Brown received nothing stating he had to get forms filled out to do interviews. In fact, the BOP Program Statement on media was updated in 2000 and indicates the “Contact with News Media” directive was rescinded.

"If they can't walk this way back to lawful behavior, they could most certainly be looking at more than just a writ of habeus corpus, they could be looking at a 1983 suit," he said. Habeus corpus petitions the court to release a prisoner who has been "illegally confined." If this were presented before a judge, BOP's legal representation may very well have said, "no thanks, you guys are correct…Oops, our bad." Since he had just gotten off a plane, "which is the story of half of my life," he hadn't yet confirmed if Siegal had pursued this route. Alternatively, however, to habeus corpus writ, a 1983 suit comprises "a violation of civil rights under the color of law," Leiderman noted, "which it appears they've done."

Under United States Code § 1983, "Every person who, under color of any statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any State or Territory or the District of Columbia, subjects, or causes to be subjected, any citizen of the United States, or other person within the jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the party injured in an action, suit in equity, or other proceedings for redress."

The law allows people "whose constitutional rights have been violated by government officials the chance to sue those officials in court," according to California Civil Rights Lawyers.