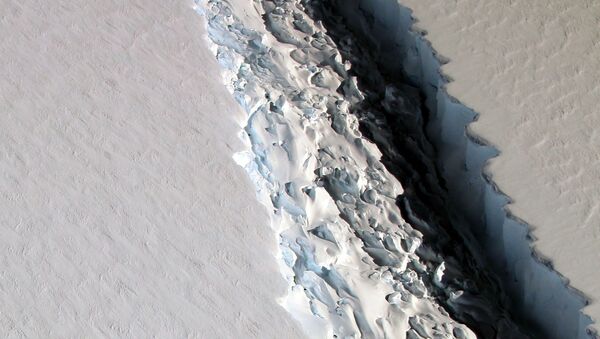

The ice shelf began to split apart in the summer of 2016, with a crack that grew quickly before slowing down. The crack is close to a year old now and is about 110 miles long. At this point, the ice shelf is hanging by a 12-mile thread that can't hold the weight for much longer.

Adrian Luckman of Project MIDAS, a British Antarctic research project that's been monitoring Larsen since 2004, says that the new crack has appeared behind the main one. "While the previous rift tip has not advanced, a new branch of the rift has been initiated," Luckman said in a statement. "This is approximately six miles behind the previous tip, heading toward the ice front."

"When it calves, the Larsen C ice shelf will lose more than 10 percent of its area to leave the ice front at its most retreated position ever recorded. This event will fundamentally change the landscape of the Antarctic Peninsula."

Since February the crack has been mostly unchanging, inching forward and widening by about three feet daily, but not matching the rapid growth it saw in late 2016, when it sometimes grew several miles in a single day.

Larsen A broke off and disintegrated in 1995, while Larsen B did the same in 2002 – but these ice shelves are small potatoes compared to Larsen C, a 19,000-square-mile titan that is the fourth largest ice shelf in Antarctica. Only a fractional chunk of Larsen C is expected to break off, about 2,000 square miles of ice.

Ice shelves breaking off or disintegrating have a more minor effect on ice levels than one might expect because they are already floating above the sea. Consider an ice cube in a glass of water: it raises the water levels when it's dropped in, but when it melts, the water levels stay the same.

The central difference between ice shelves and ice cubes is that the former can often hold in slush and water trapped inside of the ice shelf. As Luckman puts it, ice shelves "hold back the glaciers that 'feed' them. When they disappear, ice can flow faster from the land to the ocean and contribute more quickly to sea-level rise." The most generous estimates claim that sea levels will rise by 10 cm.

There is debate over whether the calving of Larsen C is the result of anthropogenic climate change. Project MIDAS wrote on their blog in February that "we have no evidence to link this event to climate change. Although the general southward progression of ice shelf decay down the Antarctic Peninsula has been linked to a warming climate, this rift appears to have been developing for many decades, and the result is probably natural."