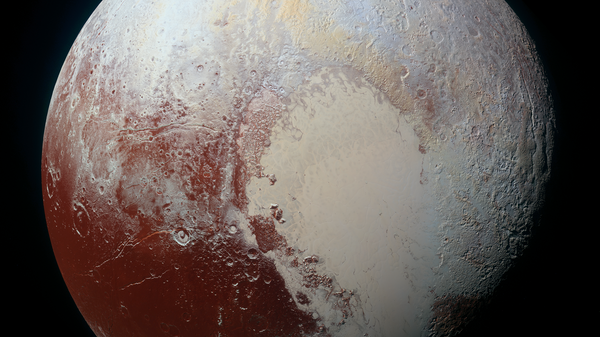

New Horizons was the first human spacecraft to visit the distant world, buts its observation time was quite brief. It reached Pluto in July 2015, took a bunch of photos, and then kissed the former ninth planet goodbye for good by October. It was but one flyby; compare it to Cassini, NASA's famous orbiter which has been orbiting Saturn for 13 years and has transmitted back astonishing amounts of information.

In late April, a group of NASA scientists met to discuss a new mission: a Pluto orbiter. Alan Stern, the principal investigator of New Horizons and renowned Pluto fanboy (he was perhaps the most outspoken opponent of Pluto's reclassification to dwarf planet in 2006,) was one of those present.

He said the meeting reminded him of the "Pluto Underground," a meeting of scientists in May 1989 that set in motion a 17-year-odyssey to launch a probe to the then-ninth planet. "It felt a lot like that, but [with] a new generation of people," said Stern to Space.com. He said that New Horizons" tantalizing look at Pluto could be greatly expanded on by a Pluto orbiter.

"You could map every square inch of the planet and its moons," he said. "It would be a scientific spectacular."

The basic plan goes like this: the probe would launch from Earth, fly for seven or eight years, and then use Pluto's largest moon Charon as a slingshot to maintain an orbit around Pluto for another four or five years. This is different from a previous plan suggested by Stern in 2015, which would have involved putting a lander on Charon.

Since Charon is tidally locked with its master, a lander would be "stuck looking at one side of Pluto," said Stern. "And you can't get in superclose. You can't get down in the atmosphere. [An orbiter], I think, is a better mission concept."

There would be additional challenges to such a mission. The orbiter would need a nuclear generator like New Horizons, as it would be too far from the sun to collect solar energy. This would make it expensive: Stern ballparked it as $1-2 billion. By comparison's sake, New Horizons cost $700 million and Cassini $3.26 billion.

Stern's vision involved finishing the orbiter in the late 2020s — or perhaps even in 2030, a serendipitous year, as Pluto was confirmed to exist in 1930. After it was finished with Pluto, Stern said, it could then journey to the Kuiper Belt to examine some of the other objects that lie at the fringes of the solar system, just like New Horizons is doing.

At the moment, an orbiter is little more than the twinkle in the eye of Stern and his colleagues. But in 2020, the US National Research Council will meet for their Planetary Science Decadal Survey and set goals for NASA for the next ten years. Stern hopes to have a mature concept ready to present at the survey by then.

"The curtain is opening," he said of the Pluto orbiter idea. "This thing is going to be a topic of discussion now for the next few years."