In his piece, Osborn recalled that that the US isn't resting on its hypersonic laurels, with a recent Air Force Studies Board report confirming that the Pentagon is fully aware that the US are not the only ones engaged in creating weapons platforms capable of moving at speeds exceeding Mach 5. Furthermore, the report indicated that these US competitors, including Russia and China, are already engaged in testing of hypersonic weapons.

Commenting on Osborn's piece, Russian military journalist and Svobodnaya Pressa contributor Vladimir Tuchkov suggested that the optimistic mood about the US developing hypersonic weapons in the near future, followed by hypersonic strike platforms after that, may be just a tad bit overoptimistic.

"In reality," Tuchkov wrote, "American scientists and engineers will have to strain every nerve just to avoid lagging too far behind Russia in this area."

In an interview with Osborn last month, US Air Force chief scientist Geoffrey Zacharias said that the US was engaged in development work on multiple fronts. "Right now we are focusing on technology maturation so all the bits and pieces, guidance, navigation control, material science, munitions, heat transfer and all that stuff," he said.

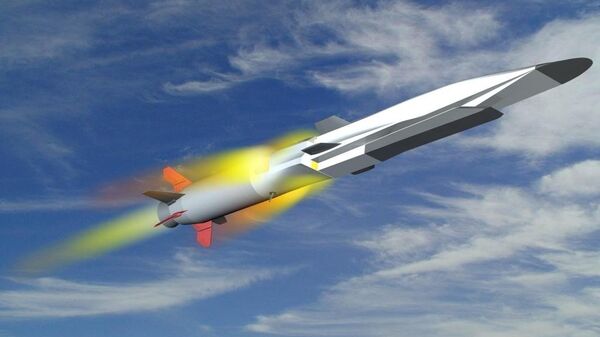

Reading Zacharias's statement closely, Tuchkov noted that the fact that the chief scientist did not name efforts to perfect the scramjet engine as one of the key scientific and engineering details to work on is indicative. "It can be assumed that the Americans are quite satisfied with what has been achieved in this area and implemented in the Boeing X-51A scramjet aircraft. Its trials began in 2010. Its estimated speed is between Mach 6 and Mach 7."

The analyst recalled that three test launches of this prototype vehicle have been carried from aboard B-52 bombers. The first, taking place in May 2010, ended with the engine speeding up the scramjet to Mach 5.1 after 210 seconds in operation, rather than the planned 300 seconds. After that, the self-destruct command was ordered, because the rocket's behavior became unpredictable.

In August 2012, a second test vehicle disintegrated over the Pacific Ocean 15 seconds into its flight.

The 2013 test was the final test in the $300 million program, started in 2004, and seen by the Pentagon as 'proof of concept' project demonstrating that a scramjet engine could go hypersonic following launch from onboard an aircraft.

However, Tuchkov stressed that "in the creation of a hypersonic aircraft, there are many equally difficult problems that must be solved, including flight-control, the exchange of information with a command point, the ability to maneuver, and targeting."

In fact, the analyst noted, "the results that the Americans reached in 2013 were achieved, and even exceeded, by the Soviet Union a long time ago."

"In the 1970s, the Raduga Design Bureau began research and development work on a project whose purpose was to study the possibility of building a cruise missile capable of reaching a speed of Mach 5. At the time, this problem had seen practically no study. The US X-15 hypersonic aircraft of the 1960s proved a failure, due to the fact that it used a liquid-fueled jet engine. It was good for space flight, but for flights in the atmosphere, a scramjet engine was required, which would use as its oxidizing material air from the atmosphere, rather than liquefied oxygen from tanks."

Tuchkov recalled that in the 1980s, Raduga was able to create several prototypes of a hypersonic cruise missile meeting this criteria, known as the Kh-90. The cruise missile, with a planned speed of Mach 5, weighed 15 tons, had a length of 9 meters, a wingspan of 7 meters, and an estimated range of 3,000 km.

"Several test flights were carried out, during which speeds from Mach 3 up to Mach 4 were gradually achieved. But in spite of these results, the project was canceled in 1992 due to the cancellation of funding."

"The same fate also befell the work of the Baranov Central Institute of Aviation Motor Development," Tuchkov recalled. "In 1979, scramjet R&D work known as project 'Kholod' ('Cold') was begun, using cryogenics technology. On the basis of a 5B28 anti-aircraft missile from the S-200 air defense system, engineers created a flying laboratory, with several variants of a scramjet tested. The best results were achieved in 1998, when a speed of Mach 6.5 was reached."

The journalist emphasized that "the Russian engineers helped the Americans, who at that time called us their 'friends', tremendously. All the test results from the Kholod flying laboratory had been sold to the US. The last test, conducted in 1998, was conducted using US funding. In other words, they received access to the program's priceless documentation."

Nevertheless, Tuchkov added that documentation or not, US engineers haven't been able to match the Kholod program's record, with the X-51A clocking in a top speed of 'only' Mach 5.1.

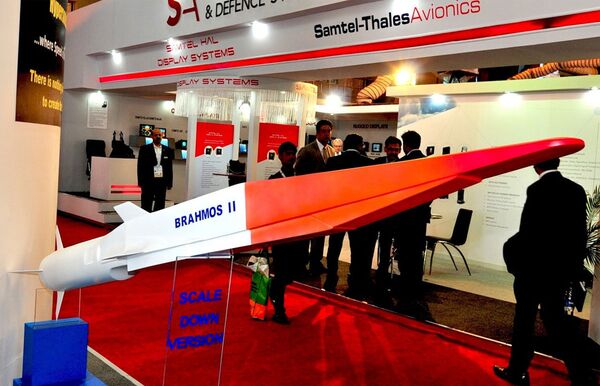

"It's interesting," Tuchkov wrote, "that Russia is mentioned only in the title of Osborn's National Interest article," with no mention made of Russia's specific programs – particularly the Zircon anti-ship missile. There is simply no way that the American military expert doesn't know about it, he added.

The 3M22 Zircon was developed in the Moscow-region city of Reutov at the NPO Mashinostroyeniya rocket design bureau. Testing began in 2015, with five successful launches achieved so far.

Tuchkov recalled that "in the last of them, a speed of Mach 6 was recorded (it should be noted that information reported in April about speeds of Mach 8 have been refuted by developers). But given the possibility of maneuvered flight, a speed of Mach 6 is more than enough of a guarantee to overcome any anti-missile system. This includes not only systems that exist today, but those expected to appear over the next two decades. Different sources place the Zircon's range between 500 and 1,000 km."

In the long run, air- and ground-based modifications of the Zircon will be created, with work on these also in progress, Tuchkov added.

"Zircon is a ready weapon in the testing phase," the expert stressed. "It is expected to be added into Russia's arsenal between 2018 and 2020. The US intends to respond to the Russian hypersonic missile in the mid-2020s. However, even these plans raise doubts."

"As mentioned above, the X-51A is not a concrete project that requires fine-tuning, but a flying laboratory. The US military industrial complex is developing a missile on the basis of the data obtained during the X-51A's tests. And developers are only at the very beginning of the road, as Russia was after the closure of the Kholod-2 program," Tuchkov concluded.