Early last week, a special mission of the Organization of American States (OAS) unexpectedly left Nicaragua two days after arriving 'in connection to broader factors not associated with the mission'. The OAS delegation had planned to hold a series of meetings with the Nicaraguan government and leaders of political parties on issues related to the improvement of the country's electoral system. The mission also intended to reach an agreement on the presence of OAS observers in municipal elections set for November.

The delegation's sudden exit and the ambiguous reasons given for the departure provoked speculation over the real reason behind their leaving. Geopolitical analyst and RIA Novosti contributor Igor Pshenichnikov suggested that the most likely reason was the US House of Representative subcommittee's recent success coming one step closer to passing a law that would issue sanctions against Managua for its alleged 'human rights violations'.

NICA would give Washington the power to block loans for the Nicaraguan government from international financial institutions if it feels that Managua has not taken "effective steps to hold free, fair and transparent elections." Experts speaking to Sputnik have warned that if it is approved, NICA's provisions could become a devastating blow to the country's economy.

Pshenichnikov emphasized that the timing of the OAS mission's hasty exit was no coincidence. The analyst recalled that notwithstanding the OAS's formal purpose and goals, it's obvious that it is an organization where the US plays first fiddle.

Earlier this year, Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega signed an agreement with the OAS under which 120 observers from the organization would work over a three year period in regions across Nicaragua to improve the country's electoral system. According to local media, this assistance was to be focused on creating a mechanism for registering votes, compiling voter lists, and other procedures related to the electoral process.

"This agreement was welcomed by the Nicaraguan authorities," Pshenichnikov noted. "The work of the OAS observers would guarantee President Ortega, who has been elected president three times in a row (not counting his presidential term between 1985-1990) protection against foreign and domestic opponents, depriving them of even a formal basis to criticize him" when it comes to democracy.

"Indeed," the journalist added, "the participation of the international community [in the form of the OAS] in the creation of a transparent electoral system in Nicaragua would have knocked the wind from the sails out of any critics of the Sandinista National Liberation Front [Nicaragua's ruling democratic socialist party] about any elections – presidential, parliamentary or municipal."

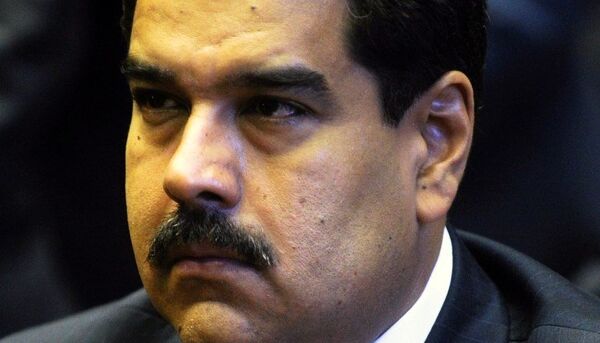

"The fact is that Nicaragua under President Ortega, like Venezuela under the late President Hugo Chavez and his successor Nicholas Maduro, are a kind of political exclave on the map of Latin America due to their openly friendly policy toward Russia. Case in point: both countries recognized the independence of Abzkhazia, and then South Ossettia, following the armed conflict in South Ossetia in 2008." After Crimea broke off from Ukraine and rejoined Russia in 2014, both countries soon made statements recognizing the peninsula as an integral part of Russia.

As for the US, Pshenichnikov recalled that Washington "has traditionally considered Latin America as part of its sphere of interests – its 'backyard', from which all other powers are banned and where…local laws and rules must be established in the interests of US corporations. It was from here that the term 'banana republic' came, used by the US as a pejorative and arrogant term to describe Latin American countries."

"In this political context, Nicaragua and Venezuela have found themselves side by side with Cuba, which Fidel Castro described as being the 'bone in the throat of American imperialism' since 1959."

In the early 2000s, the journalist noted, Venezuela under Chavez ceased to consider itself to be 'America's backyard'. "In addition to Chavez' fiery anti-American rhetoric, this was demonstrated by the withdrawal of a significant portion of control over the country's oil business by US corporations. Venezuela under Chavez had become no less of an irritant for Washington than Cuba, or Sandinista Nicaragua of the 1980s. Talk about the possibility that Chavez may have been poisoned by the Americans still has not ceased. His successor, Maduro, has said so this openly, as have Bolivian President Evo Morales, and other leaders."

Now, Pshenichnikov wrote, the US "can hardly conceal" its effort "to return control over Venezuela and its oil fields."

As for the OAS, it too is already playing an active role in promoting regime change in Caracas, the observer added. On May 20, OAS Secretary General Luis Almagro came out with a sharp criticism of Venezuelan authorities, saying the country needs to 'return to democracy', and talking about the need to 'protect human rights' in Venezuela. "As we know, Libya and Iraq were bombed, and Syria nearly destroyed, under that same pretext," Pshenichnikov stressed.

"How the riots in Venezuela, in which over 50 people have already become sacrificial victims, will end remains unclear. There, the situation is very reminiscent of the events of Maidan in Kiev in 2014: dissatisfied citizens, mass protests, killed protesters, the seizure of buildings…The script is the same everywhere. How the situation in Venezuela, against which the entire Americas have united in the face of the OAS, will end is something nobody can predict."

As for Nicaragua, Pshenichnikov noted that the withdrawal of the OAS mission, combined with the NICA bill's steady passage through US Congress, seems to indicate that the US is moving to put Managua and Ortega in the same boat as Caracas and Maduro.

At that time, "overthrowing Ortega by military force did not work. He was removed from power under the so-called 'peace process in Central America', initiated by Costa Rica under US auspices. Then, in the late 1980s, the US funneled hundreds of millions of dollars to promote the National Opposition Union of Nicaragua – which consisted of a dozen micro-parties. And the scheme worked: Ortega lost the 1990 elections. Violeta Chamorro, whose main advisors were US diplomats in Managua, became president. "

Now, unfortunately, this sad chapter in the country's history "may be repeated, amended by the Maidan-like experience gained in nearby Venezuela," Pshenichnikov concluded.