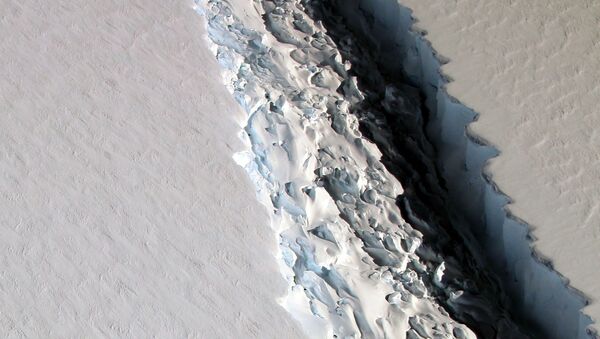

The fissure, which threatens to spawn one of the biggest icebergs ever seen, has dramatically changed direction.

"The rift has propagated a further 16 kilometers, with a significant apparent right turn towards the end, moving the tip 13 kilometers from the ice edge," said Swansea University's Prof Adrian Luckman. The calving of the iceberg could now be very close, he told BBC News, although he also quickly added that nothing was certain.

The fissure currently extends for about 200 kilometers, tracing the outline of a putative iceberg that covers some 5,000 square kilometers — an area about a quarter of the size of Wales.

The crack put on its latest spurt between May 25 and 31. These dates were the two most recent passes of the European Union's Sentinel-1 satellites. Their radar vision is keeping up a constant watch as the White Continent moves into the darkness of deep winter.

After some initial activity at the beginning of the year, the Larsen crack became stationary as it entered what is termed a "suture" zone — a region of soft, flexible ice. But this situation held only until the beginning of May, when the rift tip then suddenly forked. And it is the new branch that has now extended and turned towards the ocean.

When the iceberg's calving does finally take place, the block will likely drift away quite gradually from the ice shelf.

"It's unlikely to be fast because the Weddell Sea is full of sea-ice, but it'll certainly be faster than the last few months of gradual parting. It will depend on the currents and winds," said Professor Luckman.

Taking out such a large chunk of ice would mean the Larsen C shelf would lose more than 10 percent of its area. Previous research by the Swansea group has shown that this will put the shelf in a much less stable configuration.

Similar calving events on the more northerly Larsen A and Larsen B ice shelves eventually led to their total break-up. Scientists are concerned that this same fate could now await Larsen C.