Standing right bang on the British-Irish border on Buncrana road, you wouldn't know it's a border between two sovereign states — if not for the speed limits expressed in miles on one side of the road and in kilometers on the other.

A new and unwelcome addition to these are makeshift warning signs that this road may be closed after Brexit — the way it was during 30 years of a deadly conflict — known as the Troubles —between the pro-Irish republicans and the pro-British loyalists.

It cost over 3,500 lives, mostly civilian, between 1969 and 1998.

The border checkpoints were removed after the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 that put an end to the violence, well, to most of it. What used to be an Irish customs post is now a fireplace showroom.

Since then, people crossing the border in both directions hardly noticed it.

Photo-shy Theresa and Katrina jog across this invisible line on a quiet country lane every day — from Bridgend in the Irish Republic to Coshquin in the United Kingdom and back. Are they worried their daily jog may be cut short?

"Jogging is trivial, we can jog elsewhere. But we live in the Republic and work in the United Kingdom, so commuting through a checkpoint would be a time consuming chore. We have friends who commute in the opposite direction. Are the 'dragon's teeth' coming back to block this road? We'd rather see a united Ireland than a hard border. That's what the fight is for," one of them tells me.

Eighteen miles down south a group of kids are crossing the bridge over river Foyle which links — or separates, depending on your view — British Strabane from Irish Lifford. They live in the UK but go to the Republic to meet up with friends and family, or just for a walkabout as they say. They too would like to see a united country.

"I want to see just one Ireland, why should there be a big difference?" says the girl. "I'd like a united Ireland. If somebody asked me if I was Irish, I'd say I am Irish," the boy tells me.

When I ask whether they think a united Ireland would ever be possible, both reply:

"We can't see it happening. There's a lot of people against it."

Ireland used to be one country, but the mass colonization of Ulster by the English and the Scotts in the 17th-19th centuries led to the flight of the Irish, turning the six northern counties into a predominantly Protestant and pro-British province, which split from the overwhelmingly Catholic Irish Free State after the war of Independence in 1921.

That schism turned river Foyle into a border between the Republic and the United Kingdom.

During the Troubles of 1969-1998 Strabane was probably the most bombed town in Europe.

This stretch of the border was one of the most militarized. Many British Army regiments from the mainland did tours of duty in Strabane, based at the Barracks at "Camel's hump." Many members of those units and civilians were killed or injured in the area over the course of the Troubles that saw gun battles, car bombings, riots and pipe bomb attacks.

These days there are no British soldiers in this predominantly Irish nationalist area. But even now, after 17 years of the peace process there is an occasional explosion aimed at local police.

The kids of today can't fathom it, but Jarlath McNulty, who runs a center for Republican ex-prisoners released under the Good Friday Agreement, remembers how it used to be when he was a kid only too vividly.

"I was born in 1964, so I lived right through the whole conflict. Young people don't understand these days: you could not have worked, from one end of town to another, you had to go through checkpoints, you couldn't get through without being stopped and searched, without being arrested. When people say 'ah, it wasn't so bad,' to many people it was terrible. It left an impression upon the young lives."

"Seeing your friends getting arrested, seeing someone getting killed, there was total destruction in this town. This town was completely bombed, nearly out of existence. You had armored cars, military checkpoints, you had watch towers, surveillance, helicopters. And this is only one town scattered right along the border. You couldn't cross the border without being shot at, you couldn't go out and socialize with your friends, there always was fear. That's the type of thing — when you've lived through it — that you don't want to share with society, or your children, or your family," Jarlath tells me.

McNulty does share his experience with the younger generation to teach them the value of peace and freedom. As we talk in a local museum of the Troubles, Jarlath explains:

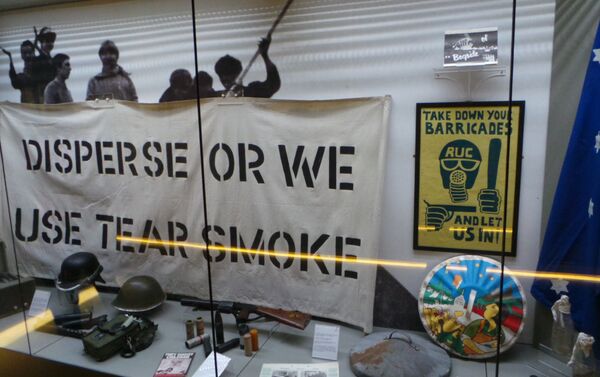

"We use this museum as a focal point for engaging with young people from the schools in the local community. If you look around the walls, you see armored cars, you see death, you see destruction. People, who've lived through all this, some still carry a lot of pain, an emotional pain, a personal pain."

It's only 14 miles along river Foyle from the most bombed town in Northern Ireland to the most infamous.

Its British name is Londonderry, but the London bit is defaced, painted or taped over on quite a few road signs leading up to the city.

Derry has gone down in history as the site of Bloody Sunday, which propelled it to international fame as a symbol of peaceful struggle for civil rights and equality, and Britain — to international infamy for killing unarmed civilians.

Thirteen people, many of them kids, were shot dead by British soldiers of the Parachute Regiment on 30 January 1972. "The death of 13 martyrs filled the Free Derry air" and spawned protest songs by John Lennon, Paul McCartney and U2 that reverberate to this day.

At the Museum of Free Derry, commemorating the victims of Bloody Sunday, I meet Jean Hegarty whose brother Kevin McElhinney was shot dead on that day.

She works at the Museum, which sits just yards away from the spot where Kevin was shot from behind while crawling to safety.

He was 17 and according to witness statements, unarmed. But that did not appear to bother the paras.

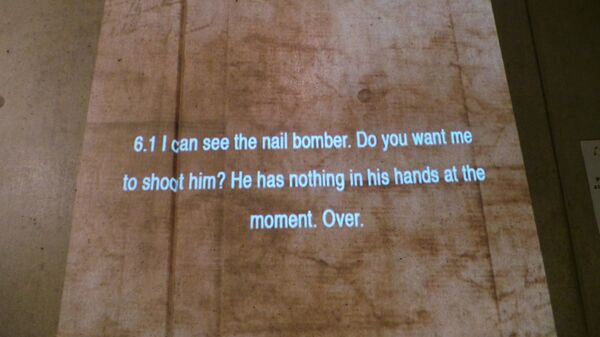

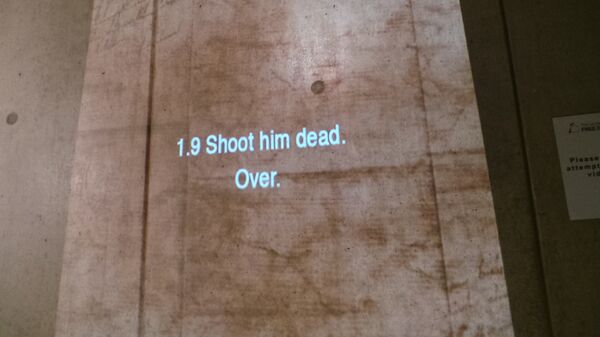

This walkie-talkie exchange among the paras, as featured in Jean's video narrative of the events of Bloody Sunday, sums up the attitude of the British military to the civil rights protesters.

"6.1 I can see the nail bomber. Do you want me to shoot him? He has nothing in his hands at the moment. Over.

"1.9 Shoot him dead. Over."

Jean Hegarty hopes her brother's death was not in vain, but the root causes of the Troubles are still there.

"He died, I am sure, for civil rights and at that time, the civil rights that they were fighting for were housing, jobs and anti-internment. My brother was a nationalist, but I doubt he was a rampant republican. He was fighting for the rights for everyone. Poor jobs affect both sides of this community. Housing historically has affected one side of the community more than the other. And those issues are still relevant," Jean tells me.

So could the Troubles return in some shape or form if Brexit forces the reintroduction of the border and another split in the community which is still coming to terms with its traumatic past?

Almost 20 years after the Good Friday agreement, Derry's Bogside is still dotted by the marks of the past.

The Irish-British border runs 4 miles to the west of Derry, but it looks like it runs right through the heart of the city itself.

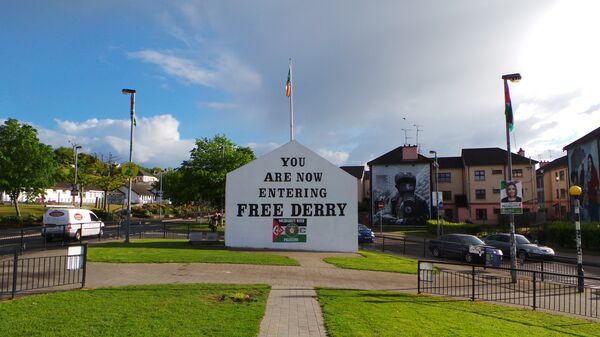

While the Bogside with its iconic "You are now entering Free Derry" headstone sports murals chronicling the oppression by the British, a staunchly loyalist area of The Fountain just a stone's — literally — throw away, is painted in Union Jack colors.

A metal gate at the entrance to The Fountain, closest to the Bogside, is locked up at 21.00 every night.

Nobody on both sides of the divide seems to want such a "hard" border between the North and the South.

Jean Hegarty remembers that even a "normal" border, without the military posts, was not a pleasant experience.

"We used to have to go through a checkpoint when we crossed the border. Quite a lot of 'unapproved' roads — you could ride your bicycle over them but you couldn't drive over them. So for a lot of those roads the same thing is going to happen again. Who knows what restrictions there will be… When I was a child there were restrictions on butter, and cigarettes and other stuff. It's like going back 50 years — 60 years almost!" Jean says.

"No it isn't!" replies Sammy Wilson, a Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) MP who's running in the snap election to retain his Westminster seat of East Antrim.

Sammy believes all this talk of going back to the days of checkpoints is just scaremongering by the Irish nationalists.

"Sinn Fein created fear through their terror campaign for 30 years and now they are trying to create fear through a psychological and political campaign that somehow other people living along the border are going to be cut off from their jobs or schools or friends or their social activities. Which is, of course, a lot of nonsense," Sammy says.

"They are an evil party! Unfortunately, lots of people vote for them in Northern Ireland. But they have evil intent and they will use these kinds of issues and these kinds of arguments. They know no bounds whether its blackmail, whether its fear, whether its threat of violence from other people. But they don't do any service to the people who live along the border by using these scare tactics."

"I don't understand the politics of fear if they are talking about bringing the debate for a new Ireland and a call to a border poll on the table. The border poll is a right under the peace agreement. And I think the border poll should happen sooner rather than later. Because it will show you a trend. And if the trend is movement towards a new Ireland then you start negotiating towards a new Ireland. And I think people who are telling us we can't have a border poll are living in the past. The Unionists do not want to give it — that's because they fear it," Jarlath argues.

Sammy Wilson insists the Unionists have nothing to fear because they are in a majority.

"Under no circumstances could you even conceive that small fraction of the 45% who voted to remain, would opt for a united Ireland. This myth has grown up that somehow the Remain vote is a vote for a united Ireland — that's not the case. Most of the Remain voters are probably unionists. And unionists, if they were faced with a border poll, would take a totally different view."

But for Jarlath McNulty it's just a question of time and demographics.

"Anyone who has any kind of sense would know that the only reason we don't have reunification is a simple head count. At the end of the day nationalists, Catholics — whatever you want to call them — they are gonna to be in a majority in the next 10-15 years. And I think you'd be better off negotiating on the new Ireland now, because it's gonna happen eventually.

"I think the Brexit situation has put the reunification back on the table for debate," Jarlath argues.

However, according to Sammy Wilson, Brexit and the border are not as prominent as they are purported to be.

"The main issue which I've got around the doors, is who will be the dominant party after this election, who will have the most votes. Sinn Fein are aiming for that, because if they do have that, it gives them the excuse to be even more trenchant and intransigent and make greater demands from the British government about the kind of aims and objectives that they have, and on the Unionist side, people are saying 'we can't allow this to happen.' " Sammy says.

As you drive into Derry across river Foyle, the first thing you see is the Hands Across the Divide monument. Unveiled in 1992, 20 years after Bloody Sunday, the sculpture of two men reaching out to each other in a handshake, is meant to symbolize the spirit of reconciliation and hope for the future.

But if you look closer, the handshake is incomplete — their hands do not touch each other. There is still some way to go, says Jean Hegarty.

"I'd like to see an end of sectarian politics in Northern Ireland. I'd like to see us have Conservatives, Labour, Liberals and the Green Party. I'd like those to be the issues that we fight elections on, but I don't think we are there yet," Jean tells me.

On a huge roundabout almost equidistant from British Strabane and Irish Lifford there stand giant metal figures of dancers and musicians, affectionately known to the locals as The Tinnies. Erected a year after the signing of the Good Friday peace agreement, they are meant to represent a shared cultural vision in an area where music and dance are great unifying and highly popular art forms. The sculpture has become one of the most photographed pieces of public art in Ireland.

There are two plaques by the ensemble, contradicting each other. The one dated 1999, the year of the unveiling of the sculptures, explains: "At the Lifford side stands a musician holding a fiddle, and at the Strabane side a musician with a fife. A drummer stands proudly between them."

The other, more recent plaque puts the fiddler on the Strabane side, and the drummer on the Lifford side, while the musician with the fife is put in between.

Because the figures stand in a circle, you can actually choose an angle to suit your preferred view of the entire Irish situation.

The border does not run across the terrain. It runs through people's minds, and now it has a name — Brexit.