According to stats published by Ukrmetallurgprom, a Ukrainian association of metallurgical plants, steel production fell by 18%, to 8.7 million metric tonsbetween January and May 2017, year on year. In the same period, output of rolled metal products dropped 20%, to 7.46 million tons, while iron production fell 22% to 7.92 million tons. Coking coal production also fell 25%, to 4.18 million tons, indicating a major drop in producer demand.

Throughout the 1990s and into the early 2010s, Ukraine enjoyed the status of a major steel-producing power. Responsible for about a third of Soviet steel production in 1990 (when the USSR was ranked number one in global steel output), Ukraine ranked fifth in the world in steel output immediately following independence in 1992. A quarter of a century later, the country faces the prospect of dropping out of the top ten producers.

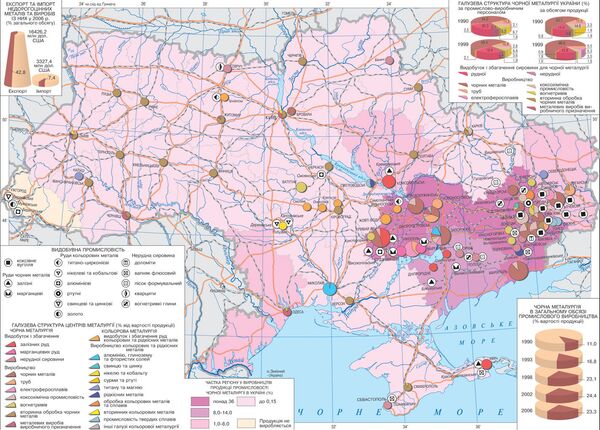

Nearly all of Ukraine's steel enterprises (which include 19 large and medium-sized mills, 12 tube mills and 20 metalware enterprises) are concentrated in an area roughly 250 by 200 km – which features good industrial and transport infrastructure, and is close to the sea ports of Mariupol and Nikolaev.

Vorobyov recalled that southeastern Ukraine has a centuries-long history of steel production. Starting in the late 19th century, it became the center of Imperial Russia's industrialization efforts, and was nicknamed the 'Russian Ruhr'. Following the Soviet industrialization campaigns in the 1930s on, by the mid-1980s, Ukraine was producing about 53-57 million tons of steel a year; in the 1990s, output fell to between 23-29 million tons, but enjoyed somewhat of a renaissance in the late 2000s, the country producing over 40 million tons of crude steel output in 2007-2008.

"It was thanks to this region that independent Ukraine was able to stabilize its economic situation to some extent after 1991. However, these times have come to an end," the journalist lamented.

These and other factors have taken a heavy toll. According to World Steel Association figures, Ukraine's total steel output dropped by 28.6% in April 2017, putting it in 14th place among 67 ferrous metal producers. Earlier this year, the Dnieper Metallurgical Combine, one of Ukraine's oldest and largest metallurgical companies, stopped output altogether.

The journalist explained that in addition to Ukraine's failure to plug in to the technologies of the third industrial revolution (including use of additive manufacturing, energy-conscious output, and use of metal substitutes), the second set of problems facing the country's metallurgical industry revolve around the country's general deindustrialization.

"It's necessary to admit that the huge industrial cluster inherited by Ukraine – including machine-building, an aerospace industry, instrument-making, transport engineering, ferrous metallurgy, the chemical industry, etc. has obviously been excessive for a country that faces impoverishment before our eyes. In the world there are no examples of the presence of advanced engineering in countries where the (nominal) per capita GDP amounts to $2,000-5,000 dollars a year," Vorobyov wrote.

This is the case "simply because these industries are too expensive for such states," the journalist noted. "There is no money for R&D, development work, marketing and promotion, payment for scientific centers, etc.…Engineers and designers receiving a [monthly] salary of $300-400 are a legacy of the Soviet system, but this system is no longer being reproduced. And in connection with the visa-free travel, the remaining Ukrainian engineers and professional workers now have a direct route to the EU…"

Last week, opposition politician Boris Kolesnikov lamented on the sorry state of the industry in the country. "We no longer produce planes and ships. If factories like the Mogilev-Podolsky [machine building plant], the Novokramatorsk and Azovmash machinery plants stop, everything will be lost. Ukraine will lose its mechanical engineering sector, and turn into a metal warehouse which is sprinkled with grain," the politician said.

Ultimately, as far as steel production goes, Vorobyov emphasized that it seems that "over the next 5-7 years, the fate of most of Ukraine's remaining metallurgical plants will be decided; some of them will be closed, others re-profiled, and Ukraine's overall smelting output will be [reduced] to 10-15 million tons per year."

"Will the world notice the loss of this [former] Eurasian metallurgical superpower? Hardly. 15 years ago, Ukraine's share of global steel production hovered between 6-7%. Now it is less than 1.5%," the journalist concluded.