In an interview for the RIA Novosti news agency earlier this week, Rogozin, whose portfolio includes the defense industry, confirmed that Russia's defense industries were in a state of "absolute readiness" to produce the Barguzin trains, along with the accompanying heavy 100-ton ballistic missile, pending a decision to include the weapons system in the state armaments program for the years 2018-2025.

Russia's Soviet-era railway missile train system, the Molodets, was officially retired from service in the mid-2000s, as part of Russia's commitment to the 1993 START-2 nuclear arms reduction treaty. START III, signed in 2010, does not prohibit development of new rail-based systems.

Last November, tests involving the Barguzin were carried out at the Plesetsk Cosmodrome in northwest Russia. Testing worked out the mechanism by which the missile leaves its railcar container, with work also carried out on the missile train's launch systems. According to media reports, development work is expected to be completed by next year, with missile flight testing starting in 2019.

Commenting on the prospective mobile strategic missile system's prospects in an analysis for Russia's Svobodnaya Pressa online newspaper, independent military analyst Vladimir Tuchkov wrote that when Barguzin is adopted into service, the rail-based component of Russia's Strategic Missile Forces will return to its early 90s-era strength, when a dozen Molodets trains carrying three RT-23 ICBMs apiece, each armed carrying ten 550k-kt MIRV warheads, cruised continuously along Russia's vast expanses.

When the Barguzin appears, it will complement Russia's air, sea and land-based nuclear triad with a separate triad within the land-based component –which will then include silo-based, mobile and rail-based ICBMs.

Furthermore, the expert noted, if reports from the defense sector and the Russian Ministry of Defense are to be believed, "the new railway missile train will significantly exceed its Soviet predecessor in terms of accuracy, range, and other characteristics, including the ability to bypass both existing and prospective missile defense systems."

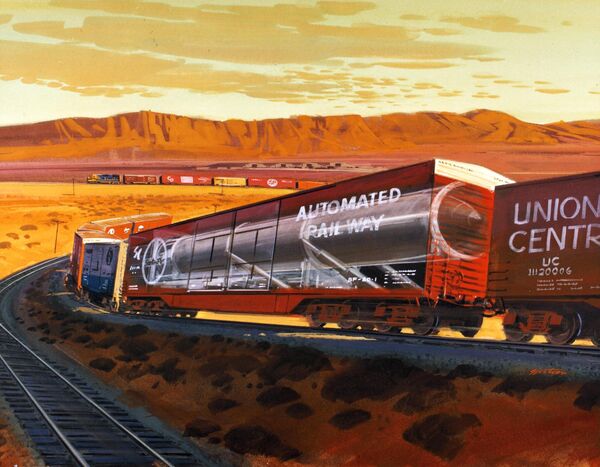

Looking back on the history of the creation of rail-based ICBM systems, Tuchkov recalled that American engineers were the first to seriously consider the idea. In the early 1960s, the Pentagon sought to create a group of thirty missile trains, each carrying five missiles.

"At the first stage, it did not seem as though a solution to this problem would be overly demanding, since developers planned to use existing Minuteman missiles," the analyst wrote. "At the same time, the missile used solid fuel, making it impervious to the shaking and vibrations experienced during rail transport. And the issue of overhead contact lines was not a problem, either, since the trains would move along non-electrified roads. However, two years into development, when the cost of development and production for the thirty missile carrying trains was calculated, the project was closed down."

The US defense industry made another attempt in the 1970s and 1980s, after intelligence reports revealed that the Soviets were working on the Molodets. "This time, they went further," Tuchkov noted. "Powerful locomotives were created, along with several launchers disguised as ordinary freight cars. These were to feature MGM-118 Peacekeepers ICBMs, with a range of 9,600 km and ten 470 kt warheads apiece."

Dubbed the Peacekeeper Rail Garrison, the US system underwent extensive testing in the 1980s. "In 1991, the test train was sent to the manufacturer for repair and radical modernization. But the system never reached the missile testing stage. In connection with the collapse of the Soviet Union and the degradation of the former Soviet Army, the Peacekeeper Rail Garrison project was closed down."

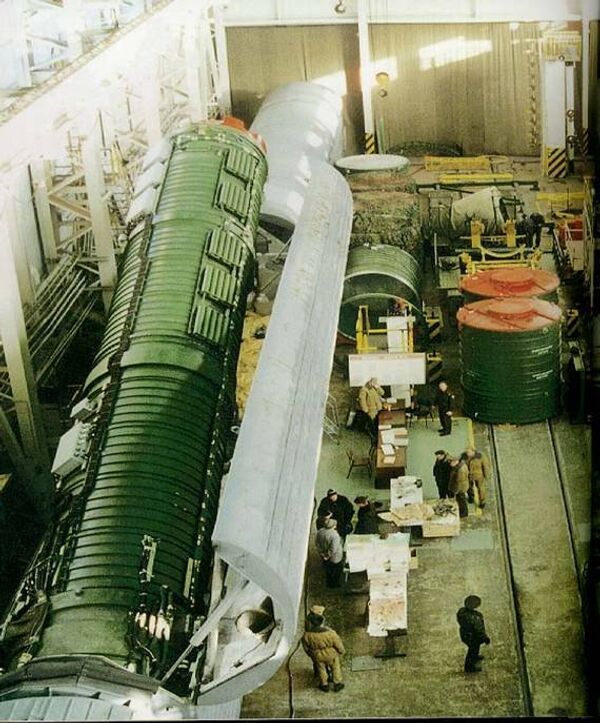

"This was a pioneering effort, given that there were no analogues either inside the country, nor anywhere else in the world," Tuchkov noted. "Therefore, only after a decade and a half, in 1989, the first train, fitted with three ICBMs, entered combat duty. Two years later, the number of these special trains grew to twelve."

Crewed by 70 troops apiece, Molodets trains were capable of operating autonomously for 28 days at a time. The trains were even designed to survive the impact of a nuclear explosion, the analyst recalled.

"In 1991, at the Plesetsk training ground, a unique experiment was conducted simulating the shockwave produced by a nuclear explosion. At a calculated distance from the Molodets, a 20-meter high, 10 meter wide pyramid consisting of East German anti-tank mines producing an explosive power of 1,000 tons of TNT was constructed. Immediately after the explosion, the Molodets launcher completed its operation normally."

The Molodets system operates as follows: "The train stops. A special device moves aside and grounds the overhead contact wire [a common feature on Russian rail networks]. The missile container is lifted to a vertical position following the moving to one side of the train car's roof. After that, the missile is pushed out of its container with its engine turned off up to a height of 20 meters. Then, the missile moves away from the train with the aid of a powder booster, and only then the engine is turned on. This avoids damage from the booster to the launcher or the railway track."

"Notwithstanding their relevance and effectiveness as a deterrent, Molodets systems did not end up serving even for five years," Tuchkov wrote. After 1991, the US began an active campaign to disarm Russia's strategic arsenal. "Half of the trains were prohibited from entering their route, and forced to stand in depots whose coordinates were known overseas. Eventually, the other half was restricted to moving no more than 20 km from their permanent bases."

"In the end, under the START II Treaty signed in 1993, Russia was obliged to destroy its RT-23UTTKh missiles, both mine shaft and rail-based. Accordingly, the unique Molodets trains were put under the knife. Ten were disposed of at the Bryansk Repair Plant. Two were handed over to museums."

As for the Barguzin, Tuchkov suggested that Deputy Prime Minister Rogozin may have misspoke with his comment about the development of a 100-ton missile for the rail-based missile system. After all, the analyst noted, the Moscow Institute of Thermal Technology, which is working on the Barguzin, has just finished development of the Yars-M, and that missile has a weight of 50 tons. Otherwise, the introduction of the Barguzin could not occur before 2025, and would require significant new spending.

In the expert's view, Yars is the missile most likely to be adapted for use by the Barguzin. "It has a longer range than the RT-23UTTX – 12,000 km instead of 10,000 km. It has fewer warheads – 6 instead of 10, and a total explosive power over three times lower. However, Yars warheads have improved capability for overcoming enemy missile defense systems thanks to their maneuverability…and use electronic warfare, and a number of other tools."

"In addition, the reduction in the weight of the missile has three significant advantages," Tuchkov wrote. "First, the train is able to carry not three, but six missiles. Second, these missiles can be placed, figuratively speaking, in a standard car, with a standard chassis not requiring compensation for the increased load on the rails. Third, the train can be serviced by a single diesel locomotive, and not by three, as was the case with the Molodets."