The 2007 airstrikes were a series of air-to-ground attacks conducted in Al-Amin al-Thaniyah, New Baghdad.

In the first, the Apaches fired on a group of ten Iraqis, including journalist Namir Noor-Eldeen and his driver and assistant Saeed Chmagh (both employed by Reuters) — seven were killed, and one injured.

Saeed Chmagh & Nanid Noor-Eldeen, @ReutersUS photographer & reporter killed by US military. #NotTheEnemy @xychelsea pic.twitter.com/PgHBZ2UQiW

— Sandy Nagy (@SandyMarieN) February 18, 2017

4/4 Reuters driver and camera assistant Saeed Chmagh killed alongside Noor-Eldeen in 2007 attack https://t.co/dXIoVIGGMf

— CPJ (@pressfreedom) January 17, 2017

Not the cameraman. The driver for the cameraman, Saeed Chmagh. Both worked for the Reuters new agency. See https://t.co/1OW8c5gqZQ

— WikiLeaks (@wikileaks) November 2, 2016

The second strike was directed at a van driven by Saleh Matasher Tomal. Both Chmagh and Tomal were killed, and two of Tomal's children badly wounded.

In the third, pilots fired on a building into which the group fled, with a volley of Hellfire missiles.

On the day of the attack, the US military acknowledged the two journalists were killed, along with nine "insurgents" — the engagement was claimed to have a combat operation against a "hostile force" in which "great pains" were taken to prevent the loss of innocent lives. Moreover, it was claimed it was unclear whether the journalists were slain by US fire or from Iraqi insurgents.

The event was consequently investigated by the US military, an inquiry which concluded the soldiers had acted entirely in accordance with the law of armed conflict, and the military's own rules of engagement.

For almost three years, despite attempts by Reuters to have footage of the incident released under the Freedom of Information Act, the deadly strikes remained largely unacknowledged, and entirely unexamined.

A mainstream media journalist, embedded with the US military at the time, mentioned the assault in his 2009 autobiography — although his account was subsequently shown to be fabricated.

The conspiracy of silence on the matter was shattered in April 2010, when WikiLeaks released footage recorded by the gunsight of one of the attacking helicopters. Dubbed "Collateral Murder" by the leak site, the video depicted the incident in full, replete with disturbingly callous radio chatter between the aircrews and ground units involved.

The exposure provoked international condemnation and widespread media coverage. Many outlets hailed WikiLeaks, and the video's (then unknown) leaker, as heroes, and the Iraq war — by then in its seventh year — became increasingly impossible for politicians, journalists and civilians to seriously defend.

While the footage shocked and appalled the world over, Josh Stieber, a member of the US military company that carried out the attack, starkly underlined just how mundane the incident was in the context of the conflict.

"When I started to see the discussion flowing from [the video], I was surprised at how extreme it was made out to be. What was shown in the video was not out of the ordinary in Iraq. One policy we had that was even more extreme was if a roadside bomb went off, we were supposed to shoot anyone standing in that area. We were told that we needed to make the local population more afraid of us," he said.

However, the revelation did not precipitate a termination of hostilities in Iraq, or prosecutions of any of the personnel involved. Instead, in May 2010, 22-year-old American Army intelligence analyst Chelsea (then Bradley) Manning was arrested after it was revealed she was the source of the leaked video, along with roughly 260,000 diplomatic cables, to WikiLeaks.

Manning proceeded to spend over three years in solitary confinement, a period which David House, founder of the Private Manning Support Network, dubbed "no-touch torture" — Manning was subjected to extended periods of isolation, harassment and sleep-deprivation.

The experience caused Manning to "physically, mentally, and emotionally" degrade over time, House said. In August 2013, she was sentenced to 35 years' imprisonment. Mercifully, in May 2017, Manning was released, following a commutation of her sentence by former President Barack Obama.

It was subsequently acknowledged Manning's disclosures did not in fact damage US interests.

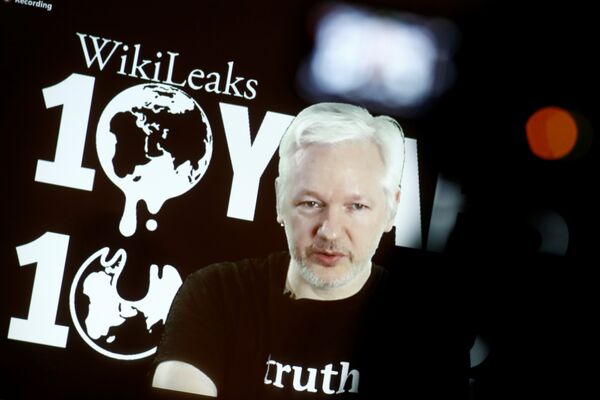

Moreover, WikiLeaks, and site founder Julian Assange, quickly found themselves the subject of US prosecutorial ire too.

In November 2010, US Attorney-General Eric Holder announced there was "an active, ongoing criminal investigation" into WikiLeaks — that same month, Sweden launched a sexual assault investigation into Assange, and issued a Europe-wide warrant for his arrest.

Residing in the UK, Assange feared extradition to the US, should Swedish — or British — authorities take him in to custody. He applied for political asylum in Ecuador, and was granted sanctuary in the country's London embassy June 19, 2012. For five years, he remained under effective house arrest, forbidden from leaving a 2,153 square foot room in the embassy's bowels, until prosecutors dumped the baseless case.

However, Assange's problems remain far from over.

London's Metropolitan Police — which stood watch outside the Embassy's door 24 hours a day, seven days a week from the moment he entered it, at an estimated cost to UK taxpayers of US$16.8 million (£13 million) between 2012 and 2015 alone — remain "obliged" to execute an arrest warrant issued in 2012 by Westminster Magistrate's Court.

The charges relate to Assange's failure to surrender to authorities. He still faces arrest if he leaves the embassy. Discussions between Assange's legal team and UK authorities on the potential cessation of bail violation charges remain ongoing.

All along, hostilities in Iraq have continued, with fluctuating levels of intensity.

"The scale and gravity of the loss of civilian lives during the military operation to retake Mosul must be publicly acknowledged. The horrors people have witnessed and the disregard for human life by all parties to this conflict must not go unpunished. Entire families have been wiped out, many of whom are still buried under the rubble today. The people of Mosul deserve to know, from their government, that there will be justice and reparation so that the harrowing impact of this operation is duly addressed," said Lynn Maalouf, Amnesty International's Middle East Research Director.