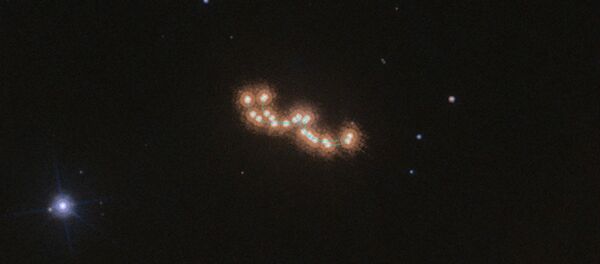

The elegantly named EBLM J0555-57Ab is located about 600 light years away as part of a binary star system. It's so small that the Cambridge team was only able to identify it when it passed in front of its much larger and brighter counterpart, in a technique called "astronomical transit" that is usually used to find moons and planets, not stars.

"Our discovery reveals how small stars can be," Alexander Boetticher, study lead and a student at Cambridge's Cavendish Laboratory and Institute of Astronomy, said in a press release. "Had this star formed with only a slightly lower mass, the fusion reaction of hydrogen in its core could not be sustained, and the star would instead have transformed into a brown dwarf."

In other words, it is unlikely for astronomers to ever to discover a star much smaller than EBLM. By definition, a star must have enough mass to allow for fusion reactions that turn hydrogen into helium. A star of similar mass but smaller size than the super-dense EBLM would likely collapse under its own weight and become a brown dwarf pseudo-star.

EBLM was identified by the Wide Angle Search for Planets (WASP) experiment, a collaboration of six UK and two Spanish universities to search for exoplanets using transit photometry. They at first believed EBLM to be a planet until realizing they had stumbled upon a particularly tiny star.

"This star is smaller, and likely colder than many of the gas giant exoplanets that have so far been identified," said von Boetticher. "While a fascinating feature of stellar physics, it is often harder to measure the size of such dim low-mass stars than for many of the larger planets. Thankfully, we can find these small stars with planet-hunting equipment, when they orbit a larger host star in a binary system. It might sound incredible, but finding a star can at times be harder than finding a planet."

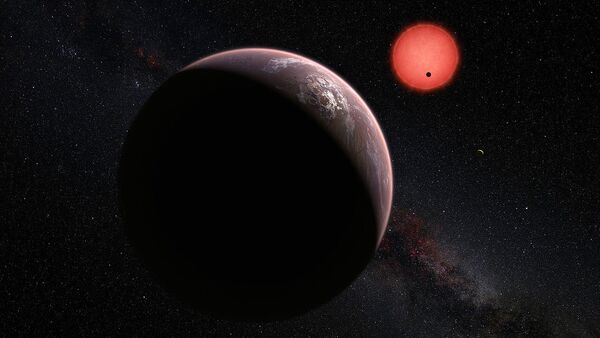

Astronomers have gained a newfound interest in these tiny, dim stars in recent years, as they have a strange tendency to be orbited by Earth-like planets. These small stars have smaller ranges by which they can capture planets in their gravity and therefore have a proportionally larger habitable zone. In other words, if a small star has planets, it has a better chance of at least one of them being Earth-like than larger stars like our sun.

For instance, TRAPPIST-1, a star with seven terrestrial planets orbiting it (three of which are in its habitable zone) is an ultra-cool dwarf star about eight percent as massive as the sun. But small as TRAPPIST-1 is, its radius still over 30 percent larger than EBLM. However, the two stars have comparable mass.

"The smallest stars provide optimal conditions for the discovery of Earth-like planets, and for the remote exploration of their atmospheres," said co-author Amaury Triaud, senior researcher at Cambridge's Institute of Astronomy. "However, before we can study planets, we absolutely need to understand their star; this is fundamental."

Astronomers wish to gain a better understanding of tiny stars such as EBLM, but the field of miniature star study is underexplored because these stars are very difficult to detect and study. In 2009, astronomers discovered the first planet orbiting a dwarf star.