A team of Columbia University astronomers believe that they have discovered the very first ever exomoon — a moon orbiting a planet besides one of the eight in our solar system.

In 1991, the first ever exoplanet was confirmed: HD 114762 b, also called "Latham's Planet." Since then, 3,621 exoplanets have been confirmed to exist. However, we had yet to confirm the existence of an exomoon: a moon that orbits an exoplanet.

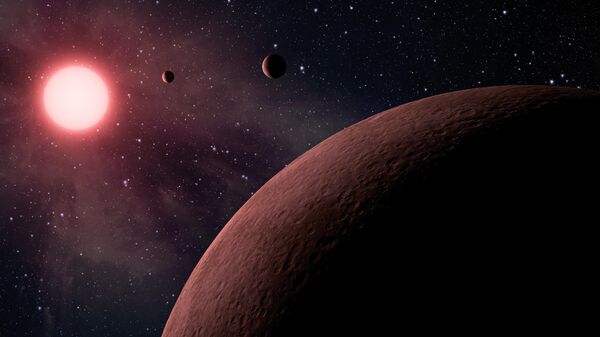

David Kipping and his team may have changed that. They were studying Kepler-1625, a star so named because it was discovered by NASA's Kepler telescope in 2016. That same year, a planet (Kepler-1625b) roughly the same size as Jupiter was discovered orbiting Kepler-1625.

Exoplanets can be found with a variety of techniques, but the most common one is known as planetary transit. When a planet passes between its star and a telescope, the star's light becomes somewhat dimmer. The telescope then images the star to find the planet.

A moon would be found with the same basic technique- waiting for it to pass between the telescope and the planet it orbits. The central issue with this is relative brightness — planets are usually hundreds of millions of times dimmer than the stars they orbit.

"Exomoons are hard to detect because moons are typically much smaller than their host planets and thus typically don't affect the transit eclipse light changes, except if the moon is large as in the case of this system," Edward Guinan, a professor of astronomy and astrophysics at Villanova University, told Gizmodo.

But Kepler-1625b is already 4,000 miles away from Earth in the Cygnus constellation — meaning it's already extremely dim. Kipping's team observed three instances of 1625b darkening that they believe are evidence of the planet's moon making a transit.

"After our largest survey to date, we have recently detected a strong candidate moon signal in the light curve of Kepler-1625b," the team wrote in a public request to observe the planet with the Hubble Space Telescope. "The planet exhibits three transits in the Kepler data (P~287 days), in which we detect out-of-transit flux dips consistent with the presence of a large moon."

Kipping's team said that they were over 99.38 percent confident that the object they had observed was an exomoon. The remaining 0.62 percent consists of flukes in the data, such as an observational error or some other spurious factor.

But they urge that they only think that they've discovered an exomoon. Speaking to Nature, Kipping urged caution to media outlets reporting the find. "It wasn't something we were planning on announcing, because at this point it's only a candidate," he says. "It really only takes the slightest misstep in our language to miscommunicate the reality of what we have."

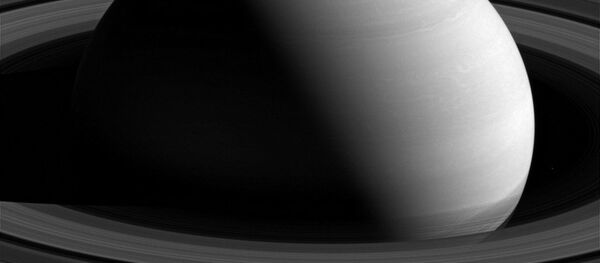

For the moon to be large enough to cause a dimming that Kepler can detect, Kipping says, it must be extremely large — to the tune of the size of Neptune, four times the size of Earth. This would make 1625b's hypothetical moon by far the largest moon ever discovered, nine or 10 times the size of current record holder Ganymede (in orbit around Jupiter.)

In October 2017, Kepler-1625b will transit in front of its star once more. This time, it will be observed by the Hubble Space Telescope. Kipping hopes that this new data will validate his theory, but it could also debunk it.