78 years ago, on August 23, 1939, Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov and Nazi German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop signed the 'Treaty of Non-aggression between Germany and the USSR', committing the countries to neutrality, and delineating the spheres of interest between the two powers.

Nearly eight decades later, the Pact continues to stir up controversy; some condemn Moscow's move, considering it an unforgivable act of collusion between the Soviet leadership and Adolf Hitler. Others claim that the agreement was a necessary breathing space for the Soviet Union to build up its defenses in time for the inevitable Nazi attack.

"In recent years, this pact has indeed received a great deal of attention," the historian noted. "However, instead of becoming an object of discussion for professional historians (who really do have differing opinions on this issue) it has acquired a political tone."

"This, of course, should have been avoided," Chubaryan said. "I support a multifactor approach to the study of history, and in order to evaluate an event, one must try to proceed from the reality of the time in which the event took place."

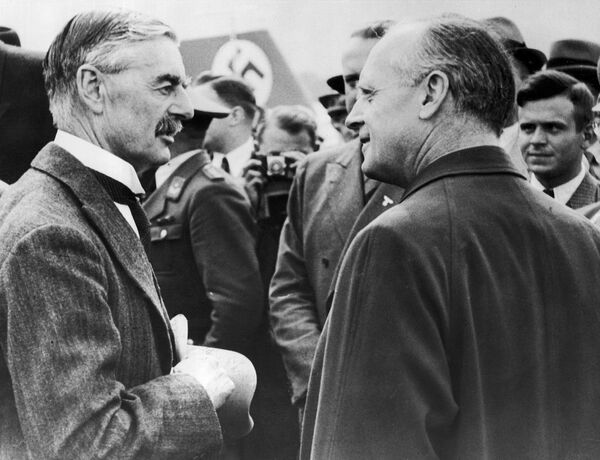

For the Soviet Union in 1939, this reality was a somber one, according to the academic. "The whole process began in September 1938 with the Munich Agreement, in which Britain and France gave Hitler part of Czechoslovakia. As [archival] documents show, the Kremlin perceived all these events as a desire to isolate the USSR in the international arena – a desire which was realized via the Munich conspiracy."

"Therefore, in the context of that time, the Soviet Union sought to overcome its isolation and create a temporary spatial field for the future confrontation with Germany," Chubaryan said.

The historian recalled that the Soviet Union was woefully unprepared for war in 1939, given the disorganized state of the military following the mass officer purges three years earlier and the on-again off-again conflict with Japan in the Far East. That is not to say that the Kremlin used the two years between the signing of the pact and the Nazi invasion in June 1941 to their full potential, the expert stressed, but they were significant nonetheless.

"I do not think that the Kremlin was hoping for long-term cooperation with Berlin," he said. "At that time, there was a general sense of the inevitability of a clash between Germany and the USSR. In the summer of 1940 it became clear that tensions were mounting. At the end of 1940, Moscow began to take intensive measures to rearm the country and to prepare it for the clash with Germany."

Chubaryan emphasized that even as a temporary, tactical move, there was a heavy price to be paid for the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, first and foremost a political one.

"Of course, something had to be sacrificed. The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact had negative consequences for the international communist movement. Anti-fascist propaganda was closed down for several months." Moreover, the USSR, which had positioned itself as the main force against fascism at the time, suffered immense reputational losses abroad, which affected the image of communist parties in other countries as well.

Asked if there was any real opportunity at the time for the Soviet Union to simultaneously avoid signing the pact and war with Germany, Chubaryan stressed that there was one chance, but that it was wasted.

These talks were destined to fail, in the historian's view, because London and Paris never seriously committed to them in the first place.

The negotiators from these countries were low-level representatives "who did not have any authority to sign an agreement. The Kremlin got the feeling that this was 'negotiation for the sake of negotiation'. In general, all the parties at the Moscow talks underestimated the danger which stemmed from German Nazism and fascism. This naturally affected their outcome."

Furthermore, Chubaryan recalled that Poland's position was a major stumbling block at the Moscow talks. "At the talks, it was discussed that in the event of a conflict, Soviet troops could be allowed to pass through Polish territory. The Poles, however, strongly opposed this idea. It's true that on August 21, France finally pressed Warsaw into agreement, but it was too late. After all, the Soviet Union received Germany's proposal to conclude an economic and political agreement," and as quickly as possible.

"Speaking of the position of the Western countries, on September 1, when the Second World War began, Poland was attacked by Germany, while France and Britain declared war, but led the so-called 'Phony War', without taking a single step to help their Polish allies."

By the time the Soviet invasion of Poland began on September 17, 1939, and annexed the predominantly Ukrainian and Belarusian lands taken by Warsaw from the fledgling Soviet state during the Polish-Soviet War of 1920-1921, the Polish military in the West had been routed, and the Polish government had reached the Romanian border, crossing into the country the next day and escaping to London.

"Everyone knows (including thanks to intelligence reports), that Hitler made the decision to attack Poland as far back as July 1939. Even the exact date of the attack was determined. Initially, it was planned for late August, but then it was moved to September 1," the scholar recalled.

Finally, so far as Warsaw's grievances today that the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact precipitated the dismemberment of Poland, Chubaryan noted that one historical fact that many prefer to leave unmentioned is that in its own time, Warsaw eagerly participated in the carve-up of Czechoslovakia following Munich, seizing territories in the country's north. While this certainly does not excuse Moscow's actions, it does give a sense of the brutal period and atmosphere in which Soviet leaders operated.

Unfortunately, the scholar noted, in Poland today, the carve-up of Czechoslovakia is recalled only by a few serious historians. "In political propaganda, attempts are made to forget this fact."