Tomoharu Oka, an astronomer at Keio University in Tokyo, told Sputnik about the importance of the find.

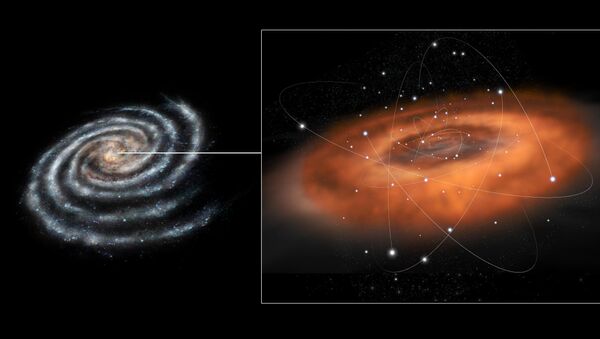

"This may be the second largest black hole in the Milky Way after Sagittarius A at the very centre of the galaxy and the first detection of an IMBH candidate in the Milky Way."

He revealed it was likely to sink into the nucleus by dynamical friction and eventually merge to it.

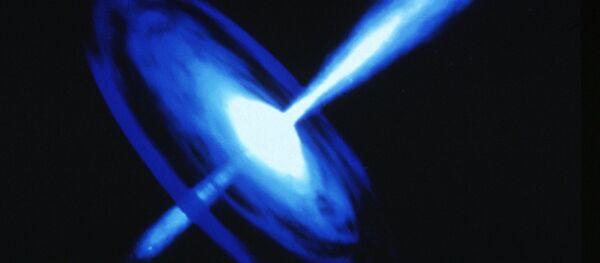

"The IMBH may have been formed by merging of stellar mass black holes. Such events generate strong gravitational waves."

Scientists in Japan believe it is a 'mini-me' version of its neighboring supermassive 'cousin' — shedding possible light on how it formed.

Looming in the middle of every galaxy, enormous black holes weigh as much as ten billion suns — fuelling the birth of stars and deforming the fabric of space-time itself. The mass of the newly identified black hole is only about 100,000 times that of our Sun — placing it in the 'intermediate sized' class.

While astronomers were aware of their existence — until now, none had ever actually been identified.

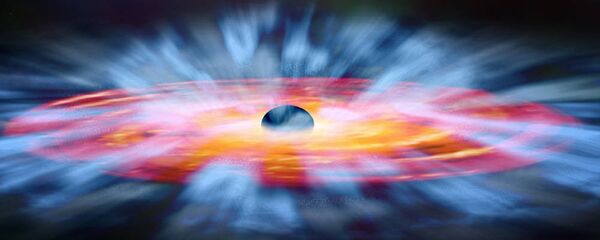

Professor Oka believes the newly found black hole may have managed to stay undetected because it is not bright, having insufficient mass accretion.

"It must be isolated, not in a closed binary system. We noticed that an inactive black hole accelerates ambient interstellar gas, which can be detected by radio telescope very easily."

Lying about 25,000 light years from Earth it could now help answer one of the main questions — how did the Milky Way evolve? Questioned over how many black holes exist in the Milky Way, Professor Oka said in theory there could be 100 million to a billion of them drifting in the galaxy.

"So far, only about 60 of them have been detected as X-ray binaries. Thus we are increasing the number of them by the new technique."

Researcher Brooke Simmons, at the University of California in San Diego, described the research as "careful detective work".

"We know that smaller black holes form when some stars die, which makes them fairly common," she explained, "We think some of those black holes are the seeds from which the much larger supermassive black holes grow to at least a million times more massive.

"That growth should happen in part by mergers with other black holes and in part by accretion of material from the part of the galaxy that surrounds the black hole."

Evidence of the new object only came to light after astronomers turned a powerful telescope based in the Atacama desert in Chile, South America, towards the gas cloud in the hope of understanding the strange movement of its gases.

Unlike those that make up other interstellar clouds, the gases in this cloud — thought to include hydrogen cyanide and carbon monoxide — move at wildly different speeds.

The scientists' suspicion that a black hole lay in the midst of the gas cloud received a boost when further observations picked up radio waves coming from the center of this cloud