Kristian Rouz – In the wake of two massive hurricanes pummeling the US, the sustainability of banking operations under extreme circumstances has become a major concern for the sector. As most advanced economies are gradually moving toward a ‘cashless society’ model, with bank transactions and various payment systems gaining a dominant position in the exchange of goods and services, unpredictable disruptions in such transactions might cause chaos, and hinder or halt consumer activity altogether.

According to the Federal Reserve, the US central bank had to allocate an additional $2.9 bln in cash to commercial banks in Florida ahead of the hurricane’s onslaught on the state. Two Fed branches in the state were working 24/7 trying to meet the demand for cash, as local residents were anticipating out-of-order cash dispensers and closed commercial bank branches due to the storm.

The price of your orange juice will probably go up, thanks to Hurricane Irma — via @grist https://t.co/tYBIxBZVjO pic.twitter.com/ZDX2xe9D7V

— Business Insider (@businessinsider) 15 сентября 2017 г.

Fed offices in Miami and Jacksonville, FL, increased their cash shipments to the local commercial bank and credit union branches twofold, as the officials were preparing their emergency response to the hurricane, trying to offset the liquidity squeeze in the state expected ahead of the storm.

They were proven right, as people headed for the local bank branches and cash dispensers, reasonably thinking the hurricane would render their plastic bankcards useless.

It did.

“It absolutely doubled our normal day-to-day operations,” Mary Gelpi of the Fed regional cash function office in New Orleans said.

The Fed banks in Florida had enough cash in the vault to double commercial bank liquidity reserves, and no cash shipments from outside of the state were required, as had been the case 12 years ago, when another massive hurricane, Katrina, ravaged Louisiana.

These measures helped meet peak consumer demand for cash, and the bank infrastructure went back online fairly quickly after the storm, allowing for the resumption of bank transactions.

“We saw the peak prior to the storm, and now the lull as people came back online and commerce is re-emerging,” Gelpi said.

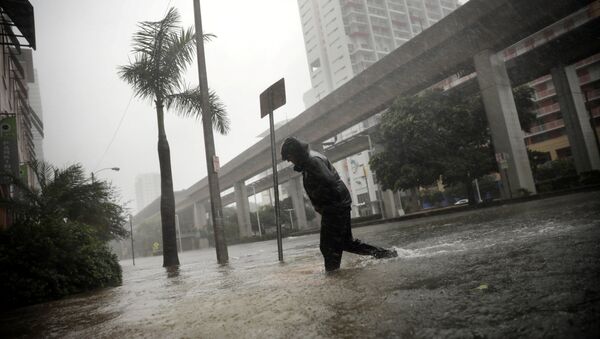

However, in August, when hurricane ‘Harvey’ hit Texas, Fed cash shipments were halted en-route, with armored trucks trapped by flooding and road blockades outside of Houston. Additional liquidity shipments had to be sent from San Antonio and Dallas. The Texas Fed banks nearly failed to provide sufficient liquidity to local consumers, but there again, the bank infrastructure went back online fairly quickly.

In Miami, the rising waters did not threaten the operation of the local Fed branch, allowing its employees to stay overnight and prepare additional cash orders for commercial lenders.

In Jacksonville, however, the Fed bank branch was almost flooded but did not take in water.

This is despite the fact that ‘Irma’ lost most of its power while ravaging the Caribbean islands, most of which now lie in rubble.

Under such circumstances, it is less likely that bank infrastructure will go back online within a matter of days, and cash reserves at home can help offset the period of uncertainty.