Teivo Teivainen, a professor of World Politics at the University of Helsinki has addressed the traditional display of swastikas in official contexts in Finland, such as on monuments, awards, logotypes and decorations for nearly a century, especially by the Finnish military, arguing that it may send a wrong message about the peaceful Nordic country.

The proud display of the swastika across Finland is known to cause some confusion around the world.

"When I first arrived in Finland, I saw a military parade with these particular insignia being flown. I was scared for my life," Keegan Elmer, an American Labor Researcher resident in Helsinki said to Finnish national broadcaster Yle. "I was very alarmed, and my friends told me to calm down," he reminisced, adding that he has had many arguments with his Finnish friends about the contentious symbol.

"One reaction, is 'don't Finnish people ever travel? Second, is 'Aren't you supposed to have good schools?' Do you even have history at school?' Or third, 'Who are these wonderfully exotic forest people that use a symbol that most of the western world has rejected?'" Teivainen explained, citing a certain kind of admiration for Finns being seen as an "almost tribal" people.

In his new book covering the history of Finland, Teivainen questioned the relevance and the potential drawbacks of using the swastika in the modern world. According to Teivainen, the fact that the Air Force Command and different branches of the Finnish Air Force still have a swastika as an official symbol may pose problems for Finland in complicated security situations.

Unwelcome topic for debate

However, this topic doesn't appear to be particularly open for debate. When trying to raise the issue, even for academic analysis, Teivo Teivainen has repeatedly run into a chilly response.

"When I talk to top politicians or people in the military about it, normally the response is that it has nothing to do with the swastika of the Nazis, that it predates the swastika of the Nazis — end of conversation," Teivainen explained.

Lieutenant Colonel Kai Mecklin, who is also the director of the Finnish Air Force Museum in the city of Vantaa, argued that the swastika has always been a symbol of independence in Finland and came into use long before the Nazis ever came into existence.

Maailmanpoliittinen kansalliskävely —kirjani pohtii myös #Karjala-olutta, Tai siis vaakunaa. Ja Vexi Salmen biisiä. #kirjamessut #montaääntä pic.twitter.com/IVGYSgWUIy

— Teivo Teivainen (@TeivoTeivainen) 7 октября 2017 г.

Finnish swastika's historic roots

Historically, the use of swastikas in Finland dates back to the early Iron Age when it was used to represent a deity from the old pagan religion. In the late 19th century, the swastika resurfaced as a symbol of rising Finnish nationalism, frequently utilized by the Fennoman movement.

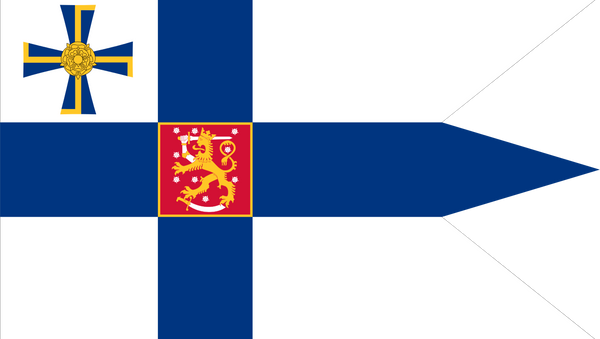

In particular, Finland's then leading painter and ardent fennophile Akseli Gallen-Kallela used the local variant of the swastika, known as fylfot, on the newborn nation's first decoration, the Cross of Liberty established in 1918. Two years later, Gallen-Kallela employed the swastika once again, in the Order of the White Rose of Finland. The symbol has since been used on war memorials across Finland and is still visible on the official flag of the President of Finland.

勘違いされることも多いのでフィンランド🇫🇮のミリタリー系の博物館や展示には必ずハカリスティとスワチカは別のものですといったペーパーがあったり文章が掲示がされたりしています。 pic.twitter.com/B0SzwZd18N

— 🍞🍞🍞 🍞🍞@芸ヵプ22 (@KiKiKi_KiKi) 30 сентября 2016 г.

Interwar period and WW2

Swastikas were a common architectural motif in the pre-WW2 years, with numerous buildings erected in the 1920s and the 1930s still displaying the contentious symbol.

Furthermore, the swastika has been utilized by the Finnish Air Force since 1918, as a tribute to Swedish aviator Count Eric von Rosen, who donated one of his planes to the White Forces in Finland's Civil War. Von Rosen adopted the swastika as his good luck charm as early as 1901. The Finnish Air Force used the swastika as its insignia between 1918 and 1945, and it can still be seen on the flag of the Finnish Air Force Academy.

.@suski_kaukinen #Puolustusvoimat on, mutta #Ilmavoimat ei ole koskaan siitä #Svastika'sta luopunutkaan. pic.twitter.com/738kzm5rMd

— asiamies (@asiamies1) 5 февраля 2016 г.

The swastika was also employed as the logotype of Lotta Svärd, a Finnish auxiliary paramilitary organization. Lotta Svärd, which drew its name from a character featured in a poem by Finnish national poet Johan Ludvig Runeberg, the author of the national anthem, was associated with the White Guard during the Finnish Civil War. During WW2, it grew to become the world's largest voluntary organization, featuring 242,000 members of Finland's total population of less than four million.

also the symbol of lotta svärd, finnish paramilitary organisation for women in ww2. pic.twitter.com/lYtTi18yaU

— sini. ♔ (@brilliantblue_) 14 октября 2016 г.

Finland's role in WW2 remains a sensitive topic, as is the country's Civil War in 1918. In WW2, Finland fought against the USSR as a co-belligerent of Nazi Germany, receiving aid and assistance until the armistice with Moscow in the early autumn of 1944, whereupon the Finns turned their arms against their former allies. After the war, the victorious Soviet Union voiced objections to the continued use of the swastika as a motif for the Finnish Armed Forces, following which most emblems have been purged of the symbol, despite erratic attempts to reinstate the swastika by President Urho Kekkonen.

Finnish Airforce LeLv 34, Messerschmitt Bf-109 G-2 MT-203, MT-214 and MT-216, 24 April 1943 at Utti, Finland. Color by Tommi Rossi #WWII pic.twitter.com/8AmCKDd3xZ

— FinnishWartimePhotos (@FinnishWarPics) 5 января 2017 г.

A sense of belonging

According to Professor Teivainen, many Finns paradoxically still see the swastika as a token of togetherness with the West.

"It's a funny thing, that many people in Finland say 'why should we let the Russians interfere with what we do?', and they present the swastika today in the Finnish military as a kind of symbol of belonging to the West, a sort of 'the Russians can't tell us what to wear and what symbols to use,'" Teivainen argued, contending that this statement would sound hilarious in the rest of Europe.

According to Teivainen, the current perception of the swastika has even created "false memories" such as the erroneous belief that the "Finnish" swastika faced left, unlike the right-facing Nazi one. Teivo Teivainen is not convinced that the idea of Finland's own swastika, completely separate from the international perception of it, holds water. While not advocating a ban on swastikas as such, Teivainen questions the benefits of their continued use as official symbols.

People react in various ways to this drawing of a Finnish soldier with #swastika flag. Some think it is from the past, others say future. pic.twitter.com/blPlwvVzxG

— Teivo Teivainen (@TeivoTeivainen) 10 октября 2017 г.

Teivo Teivainen is a professor of World Politics at the University of Helsinki and the founding director of the Program on Democracy and Global Transformation at the National University of San Marcos in Lima, Peru.

Teivo Teivainen lavalla klo 12.40. Teemana kansallisen symbolit kuten kuvassakin #kirjamessut#montaääntä @TeivoTeivainen pic.twitter.com/0dNo5tH9X6

— Kirjamessut Turku (@Kirjamessut) 8 октября 2017 г.