For such people it commands greater importance than the Reformation or the American and French revolutions preceding it, in that it went further than religious or political emancipation to engender social emancipation; and with it an end to the exploitation of man by man which describes the human condition fashioned under capitalism.

The attempt to place communism and fascism in the same category is, however, facile in the extreme — a depiction that fails the test of history. The real and historically accurate relationship between both of those world-historical ideologies is that whereas fascism was responsible for starting the Holocaust, it was communism — in the shape of the Soviet Red Army — that ended it.

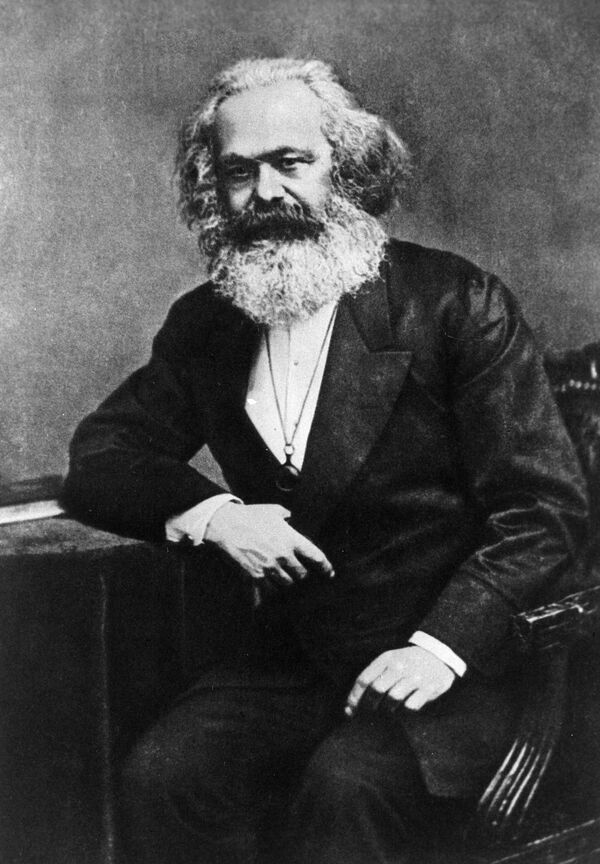

That Russia in 1917 was the least favorable country of any in Europe for socialist and communist transformation is indisputable. The starting point of communism, Marx avers in his works, is the point at which society's productive forces have developed and matured to the point where the existing form of property relations acts as a brake on their continuing development. By then the social and cultural development of the proletariat has incubated a growing awareness of their position within the existing system of production; thereby effecting its metamorphosis from a class "in itself" to a class "for itself" and, with it, its role as the agent of social revolution and transformation.

Marx writes:

"No social order ever perishes before all the productive forces for which there is room in it have developed; and new, higher relations of production never appear before the material conditions of their existence have matured in the womb of the old society itself."

The error in Marx's analysis was that rather than emerge in the advanced capitalist economies of Western Europe, communism emerged on the periphery of the capitalist centers — Russia, China, and Cuba et al. — in conditions not of development or abundance but under-development and scarcity.

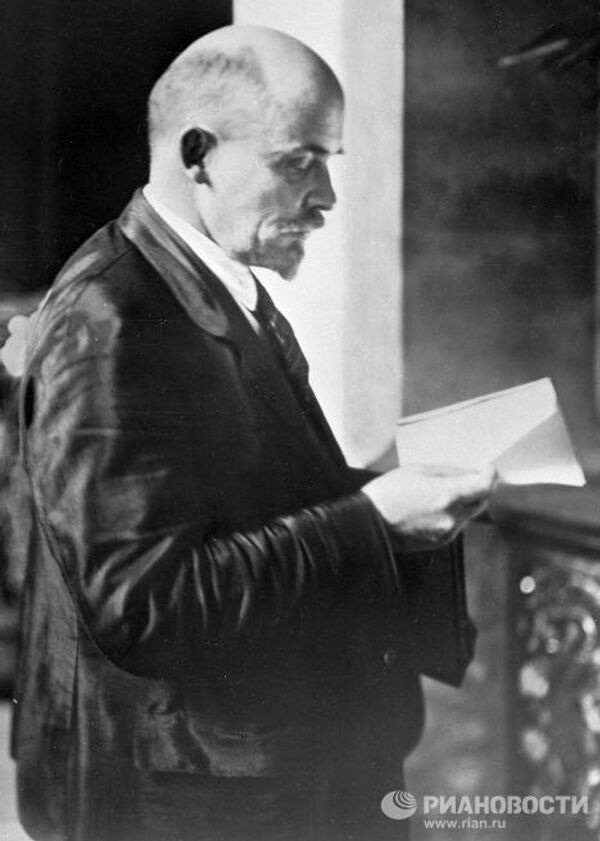

From the vantage of exile in Switzerland, Lenin saw with uncommon clarity how the First World War presented revolutionaries across Europe with a clear choice. They could either succumb to national chauvinism, fall into line behind their respective ruling classes and support their respective countries' war efforts, or they could use the opportunity to agitate among the workers of said countries for the war to be turned into a civil war in the cause of worldwide revolution.

It was a choice separating the revolutionary wheat from its chaff, leading to the collapse of the Second International as with few exceptions former giants of the international Marxist and revolutionary socialist movement succumbed to patriotism and war fever.

Lenin observed:

"The war came, the crisis was there. Instead of revolutionary tactics, most of the Social-Democratic [Marxist] parties launched reactionary tactics, went over to the side of their respective governments and bourgeoisie. This betrayal of socialism signifies the collapse of the Second (1889-1914) International, and we must realize what caused this collapse, what brought social-chauvinism into being and gave it strength."

The ensuing chaos, carnage, and destruction wrought by four years of unparalleled conflict brought the so-called civilized world to the brink of collapse. The European continent's ruling classes had unleashed an orgy of bloodshed in the cause not of democracy or liberty, as the Entente powers fatuously claimed, but over the division of colonies in Africa and elsewhere in the undeveloped world.

From the left, or at least a significant section of the international left, the analysis of October and its aftermath is coterminous with the deification of its two primary actors — Lenin and Trotsky — and the demonization of Stalin; commonly depicted as a peripheral player who hijacked the revolution upon Lenin's death, whereupon he embarked on a counter-revolutionary process to destroy any prospect of the working class democracy it was designed to harness coming into being.

Writing in the second volume of his magisterial three-part biography of Leon Trotsky, The Prophet Unarmed, Isaac Deutscher describes how the Bolsheviks were aware that "only at the gravest peril to themselves and the revolution could they allow their adversaries to express themselves freely and to appeal to the Soviet electorate. An organized opposition could turn the chaos and discontent to its advantage all the more easily because the Bolsheviks were unable to mobilize the energies of the working class. They refused to expose themselves and the revolution to this peril."

The harsh reality is that the cultural level of the country's nascent and small proletariat, whose most advanced cadre was destined perish in the civil war, was too low for it to take the kind commanding role in the organization and governance of the country Lenin had hoped and anticipated. "Our state apparatus is so deplorable," he was forced to admit, "not to say wretched, that we must first think very carefully how to combat its defects, bearing in mind that these defects are rooted in the past, which, although it has been overthrown, has not yet been overcome, has not yet reached the stage of a culture, that has receded into the distant past."

Stalin's victory in the struggle for power within the leadership in the wake of Lenin's death in 1924 was, if conventional wisdom is to be believed, down to his Machiavellian subversion and usurpation not only of the party's collective organs of government, but the very ideals and objectives of the revolution itself with a view to embarking on counter-revolution. However, this describes a reductive interpretation of the seismic events, both within and outwith Russia, that were in train at this point.

Despite Trotsky's determination to hold onto the belief in the catalyzing properties of October with regard to European and world revolution — which he shared with Lenin — by 1924 it was clear that the prospect of any such revolutionary outbreak in the advanced European economies had ended, and that socialism in Russia would have to be built, per Bukharin, "on that material which exists."

Trotsky and Lenin's faith in the European proletariat proved wrong, while Stalin's skepticism in this regard proved justified. Returning to Isaac Deutscher:

"After four years of Lenin's and Trotsky's leadership, the Politbureau could not view the prospects of world revolution without skepticism… Stalin was not content with broad historical perspectives which seemed to provide no answer to burning, historical questions… extreme skepticism about world revolution and confidence in the reality of a long truce between Russia and the capitalist world were the twin premises of his [Stalin's] socialism in one country."

The five-year plans introduced by Stalin, beginning in 1928, were undertaken in conditions of absolute necessity in response to the gathering storms of war in the West: "We are fifty or a hundred years behind the advanced countries," Stalin declared in 1931. "We must make good this lag in ten years. Either we do it or they crush us."

When it comes to those who cite the undoubted brutal human cost of October and its aftermath as evidence of its unadulterated evil, no serious student of the history of Western colonialism and imperialism could possibly argue its equivalence when weighed on the scales of human suffering. Here Alain Badiou reminds us that "the huge colonial genocides and massacres, the millions of deaths in the civil and world wars through which our West forged its might, should be enough to discredit, even in the eyes of ‘philosophers' who extol their morality, the parliamentary regimes of Europe and America."

Ultimately, no revolution or revolutionary process ever achieves the ideals and vision embraced by its adherents at the outset. Revolutions advance and retreat under the weight of internal and external realities and contradictions, until arriving at the state of equilibrium that conforms to the limitations imposed by the particular cultural and economic constraints of the space and time in which they are made.

Though Martin Luther advocated the crushing of the Peasants Revolt led by Thomas Munzer, can anyone gainsay Luther's place as one of history's great emancipators? Likewise, while the French Revolution ended not with liberty, equality, fraternity, but Napoleon, who can argue that at Waterloo the Corsican general's Grande Armee was fighting in the cause of human progress against the dead weight of autocracy and aristocracy represented by Wellington? In similar vein, Stalin's socialism in one country and resulting five-year plans allowed the Soviet Union to overcome the monster of fascism in the 1940s.

This is why, in the last analysis, the fundamental metric of the October Revolution 1917 is the Battle of Stalingrad in 1942. And for that, whether it cares to acknowledge it or not, the world will forever be in its debt.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of Sputnik.

Check out John's Sputnik radio show, Hard Facts.