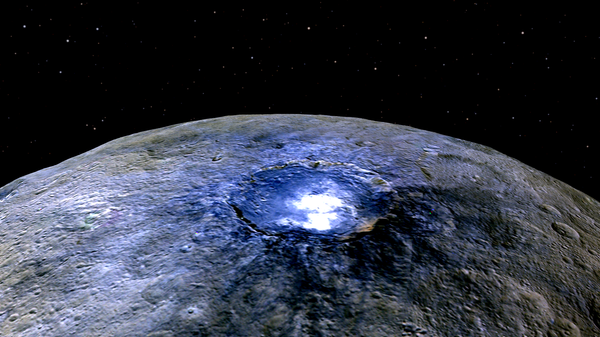

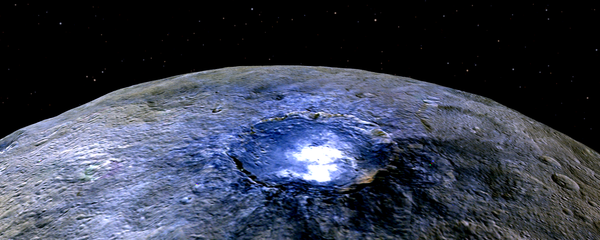

The idea that Ceres, located in the asteroid belt, might have a subterranean ocean, existed before 2015, when Dawn first approached the dwarf planet. Now, two new studies now back up this theory.

The evidence was acquired by measuring small changes in Dawn's orbit, thanks to what are called "gravity anomalies." Simply stated, those anomalies are discrepancies between the actual measured gravity and what the scientists would expected it be. Those discrepancies are probably caused by solid mountains beneath the relatively flat crust of Ceres.

"Ceres has an abundance of gravity anomalies associated with outstanding geologic features," Ermakov said.

In addition, the study also determined that the planet's crust is not dense enough to be rocky, Phys.org reports. In fact, it appears to be made of water ice. But as ice is too soft to support such a massive structure as the dwarf planet's outer shell, scientists were left scratching their heads.

Another study, this one by Roger Fu at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, may shed some light on this planetary paradox. Fu's team found that Ceres' crust is most likely made of "a mixture of ice, salts, rock and an additional component believed to be clathrate hydrate." The latter is a material made up of water molecules surrounding a gas molecule. This material, while being 100 to 1,000 times stronger than ice, is still very light.

This has led scientists to believe that the dwarf planet once had a much more dramatic topography, but has since flattened to mere "gravity anomalies." Such erosion would require polishing by something like an ocean of water.

That water is believed to be mostly frozen now, making up most of the planet's outer shell. But looking at the way the shell moves, the scientists have come to conclusion that some residual liquid might still be hiding on it somewhere.

The scientists have to rely on distant methods of measurement because landing directly on the dwarf planet would be both technically complicated and would possibly contaminate the celestial object, according to Phys.org.