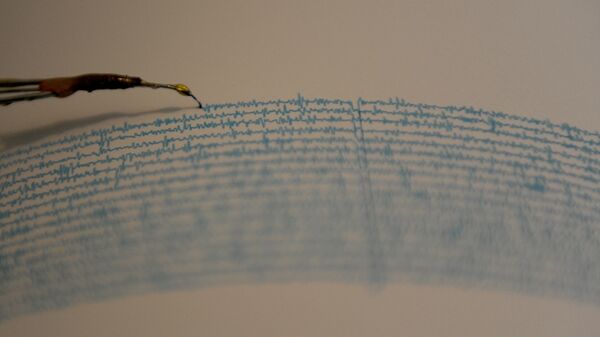

In a paper published in Geophysical Research Letters in August and presented at the annual meeting of the Geological Society of America last week, Robert Bilham of the University of Colorado and Rebecca Bendick of the University of Montana studied every earthquake since 1900 with a magnitude 7.0 or greater on the moment magnitude scale.

"Major earthquakes have been well recorded for more than a century and that gives us a good record to study," Bilham told the Observer last week.

They noticed that about every 32 years there is a spike in large earthquakes. They also uncovered that the Earth's rotation, which follows a cyclical pattern of slowing and then speeding back up, slowed for a five-year period before each uptick in quakes.

"In these periods, there were between 25 to 30 intense earthquakes a year. The rest of the time, the average figure was around 15 major earthquakes a year," Bilham said.

"It is straightforward," Bilham added. "The Earth is offering us a five-year heads-up on future earthquakes."

This is particularly relevant now because Earth began one of its periodic slowdowns more than four years ago, which means that we may see an uptick in earthquakes very soon.

"The interference is clear. Next year, we should see a significant increase in numbers of severe earthquakes. We have had it easy this year. So far we have only had about six severe earthquakes. We could easily have 20 a year starting in 2018."

Scientists don't know yet why the speed of Earth's rotation correlates with the frequency and intensity of earthquakes, but one theory is that changes in the flow of molten iron in Earth's outer core could affect both the planet's spinning speed and seismic frequency.

Although more research is necessary to fill in the gaps, other scientists believe the question is certainly worth looking into.

"The correlation they've found is remarkable, and deserves investigation," University of Colorado geologist Peter Molnar told the Guardian.