The Irish Government issued a terse warning to British Prime Minister Theresa May's government on November 21, threatening to veto any UK-EU trade agreement that makes a hard border with Northern Ireland a possibility, while on November 17 the Irish PM Leo Varadkar demanded written assurance from London that a hard border was not a possibility as a precondition for trade talks going ahead.

During the BBC TV program Question Time on November 22, Theresa May explicitly denied that a hard border would be imposed after Britain leaves the European Union in March 2019. The UK government has however, repeatedly ruled out any possibility of Northern Ireland remaining in the customs union or having any separate status that lessens Britain's sovereignty over the country.

Former US diplomat and mediator for political talks in Northern Ireland from 2001-2003 and 2013, Richard Haas tweeted November 21 that Northern Ireland is reaching a "crisis point" as a result of Brexit and expressed hope that the violence of The Troubles would not resume if the political crisis worsened.

Northern Ireland at a crisis point, the result of poor leadership, Brexit, & a failure to deal with the past. agree that the current impasse likely to lead to restructuring of its politics and/or push for Irish unification. hoping it does not lead to any resumption of violence.

— Richard N. Haass (@RichardHaass) November 21, 2017

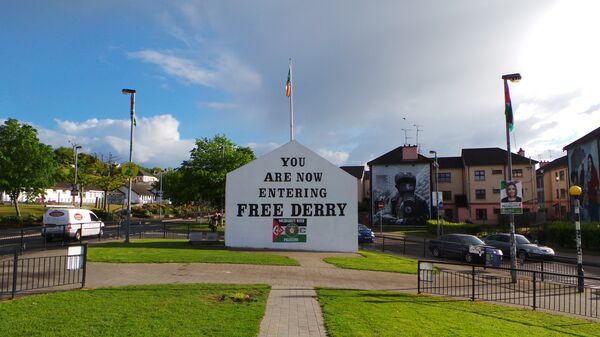

Fears have grown among many observers since the 2016 Brexit referendum result that a renewed border would undermine the crucial Good Friday Agreement which has kept the peace in Northern Ireland since 1998, ending the period of paramilitary and sectarian violence between 1968 and 1998 known as The Troubles.

Roger MacGinty, Professor of Peace and Conflict Studies at the University of Manchester told Sputnik that Dublin was unlikely to cede any ground on the issue, as it has the support of all other EU-member states.

"The Irish government has no incentive to make this easy for the UK. They see it as an act of supreme selfishness by the UK and most other EU governments are lining up to agree with them," Professor MacGinty told Sputnik.

Professor MacGinty added that public opinion on the island is united in opposition, both to Brexit and the re-establishment of a hard border and a resumption of historic violence due to the freedom of movement the peace-process and EU integration has brought and the ease of doing business across Ireland.

"They remember a hard military border with checkpoints and long traffic queues. They are bewildered at why anyone would want to go back to that. Businesses see Brexit as crazy. The whole point of the Good Friday Agreement was to grow relationships across Ireland and across the British Isles. Erecting a border does nothing for that," Professor MacGinty explained.

Damage to the Peace Process

Northern Ireland has been without a government since January 2017 when the power-sharing arrangement between Sinn Fein and the Democratic Unionist Party collapsed.

Adrian Guelke, Professor Emeritus of at the School of History at the University of Belfast told Sputnik however, that both the UK and Ireland, with the EU behind it, are increasingly in a position in which neither can afford to compromise and mitigate the threat of a hard border.

"The bottom line is that the UK's departure from the EU is damaging to the peace process. If Brexit can't be reversed, then next best is discussion of various ways of mitigating the damage, though even this seems extremely difficult, given the stance of the London government and of the DUP on membership of the single market, the customs union and treating Northern Ireland differently from the rest of the UK," Professor Guelke said.

The Government of Ireland Act of 1920 created the modern Irish Republic but also partitioned the north of the island between the newly independent Catholic-majority state and six largely Protestant counties which remained part of the United Kingdom.

The division led to intense paramilitary and sectarian violence throughout much of the twentieth century. The height of the violence from 1968 to 1998 came to be known as The Troubles, which saw spectacular terrorist bombings such as in the town of Omagh where 29 people were killed and even attempted assassination of UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in the 1984 Brighton Hotel Bombing.