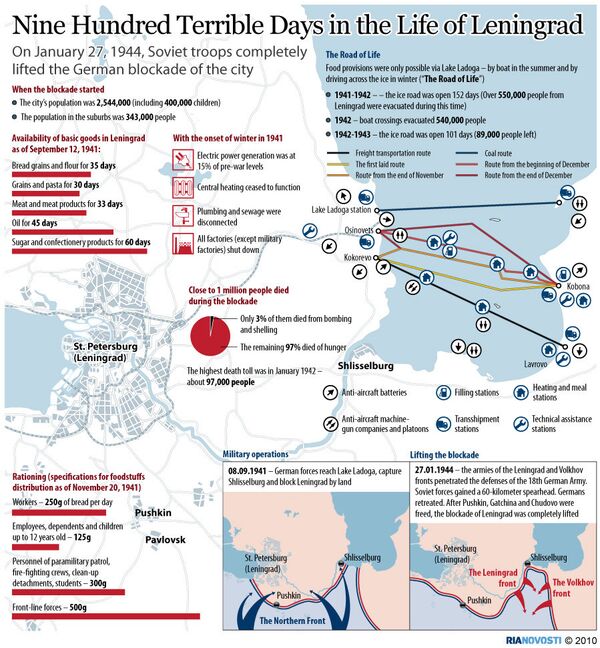

The ice road, which allowed for the delivery of hundreds of thousands of tons of food, supplies, and ammunition to the besieged city, also allowed over 550,000 of Leningrad's population of 2.5 million people to be evacuated during the time that the ice road remained open. It also carried wounded soldiers, industrial equipment and particularly valuable works of art and museum pieces from the city's rich collection of cultural heritage to safety. From late 1942 to early 1943 and until the Red Army advanced and the siege was lifted, a total of 1.376 million civilians and military personnel evacuated with the help of the Road of Life.

Military logistics commanders officially adopted a decree 'On the Organization of the Construction of an Ice Route on Water From the Osinovets Cape to the Karedzha Lighthouse' on November 13, 1941. army engineers commanded by military engineer B.V. Yakubovsky surveyed the lake for a route where ice was thickest, a task complicated by the lake's immense size and fluctuating weather conditions. The first caravan of 60 GaZ-AA trucks, loaded with flour and commanded Captain V.A. Porchunov, started its perilous journey to the besieged city on November 22, 1941.

"After the defeat of Soviet Russia there can be no interest in the continued existence of this large urban center…Following the city's encirclement, requests for surrender negotiations shall be denied, since the problem of relocating and feeding the population cannot and should not be solved by us. In this war for our very existence, we can have no interest in maintaining even a part of this very large urban population."

Adolf Hitler sent a similar directive to Army Group North on October 6, ordering the army not to accept any surrender offers, although Soviet forces had no intention of doing so. The city, bearing the name of the USSR's founder, Vladimir Lenin, was also a major industrial and port city, and the base for the Soviet Navy's Baltic Fleet.

Instead, starting in September, when the city's defenders became totally pocketed in the narrow strip of land between the Gulf of Finland and Lake Ladoga, the Soviets began to use Lake Ladoga as a means to supply the area, first by ship, and later, as winter set in, via an ice road lifeline.

Amid the success of the truck-based lifeline, military engineers also established a rail line, along with an oil pipeline to supply the city's military and civilian transport with fuel.

The route was extremely dangerous, with trucks often falling into the ice and sinking to the bottom of the lake. The situation was complicated by constant German artillery shelling and Luftwaffe bombing from the air. Nevertheless, even into the spring of 1942, when the ice began to melt from under them, the supply trucks continued to make their treacherous journey, a powerful image first shown to Western audiences by Frank Capra in his 1943 documentary Why We Fight: The Battle for Russia.

As of mid-February 1942, about 15,200 people, over 4,200 vehicles, 140 tractors and 540 horses were involved in the supply operation, its numbers shifting throughout the war. During its existence between 1941-1943, the Road of life delivered an estimated 1.615 million tons of supplies, allowing Leningrad to hold out until Operation Spark, a full scale-offensive by troops from the Leningrad and Volkhov Fronts in late January 1943, which opened a land corridor to the city on January 27, 1944, and proceeded to liberate the northern USSR from the Nazi scourge in the months that followed. For its heroic resistance in the face of overwhelming odds, Leningrad was awarded the title of Hero City in 1945, becoming the first city to receive the title.