Yehuda Kimani, a 31-year-old Jewish convert, believed he had the permission of the Israeli ambassador in Nairobi to study at a Conservative yeshiva in Israel, but when he arrived at Ben-Gurion Airport in mid-December to begin his studies, he found border authorities had different ideas.

Kimani was detained and not allowed to contact his sponsors in Israel, according to Haaretz, and put on a plane to Ethiopia the following morning. According to the Jerusalem Post, officials feared "he would remain [illegally]" in the country after his three month visa expired. Why Kimani was suspected of such duplicity, the Interior Ministry never said.

Though Kimani hails from Kenya, since 2010 he has been a member of a Ugandan community of Jewish converts called the Abayudaya, whose Jewish status with regards to the Jewish State is in limbo. Although the Abayudayas ceased practicing Christianity and began observing Jewish customs nearly a century ago, only in 2002 did they receive official conversion by a Conservative rabbi. Another group converted in 2008, and the community today numbers between 1,500 and 2,000 members.

Abayudaya status with Israel is a confused mess: although Birthright recognizes them as Jewish, the Jewish Agency only recognizes converts since 2009 as Jews, since that is when they joined the world Conservative movement. However, the Israeli Interior Ministry, which gets the last word on who is and is not Jewish (and thus entitled to immigrate to Israel by the Law of Return), does not currently recognize any Abayudayas as Jews.

It was on that note that Amos Arbel, director of the ministry's Population Registry and Status Department, replied to questions about Kimani's situation by saying, according to Haaretz: "Sorry to say this, but for us he is a goy from Kenya."

Since the Interior Ministry doesn't consider Kimani to be Jewish, and yeshivas are non-degree-conferring institutions, Arbel explained that Kimani's visa was denied because only Jewish applicants are given visas to study at such institutions. This ignores the fact, of course, that Kimani's visa was approved and stamped by the Israeli consulate in Nairobi in November, the Jerusalem Post reported in December.

'Do you want half of Africa coming here?'

With this line, Arbel fired back at critics of Kimani's deportation, touching on a much larger issue at hand: Israel's troubled relationship with African immigrants and Mizrahi Jews.

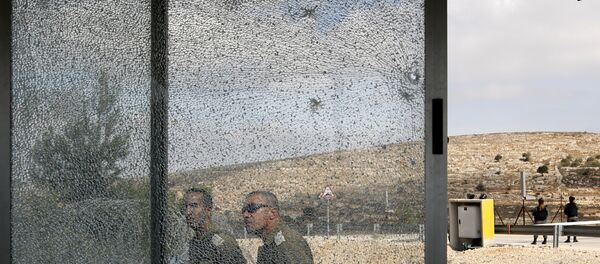

On Wednesday, the Israeli cabinet approved a plan and budget to deport 35,000 African immigrants by the end of March, according to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Targeting primarily asylum-seekers from Sudan and Eritrea, migrants who do not voluntarily exit the country or accept a $3,500 settlement to do so will be detained in a Negev prison facility, perhaps indefinitely, according to the Jerusalem Post.

Israel has approved only 1 percent of all asylum requests, according to the Jerusalem Post.

Deportees will be sent to either Uganda or Rwanda, part of a tactic to sidestep international laws that bar repatriation of refugees to the country from which they are fleeing. According to the Jerusalem Post, the Rwandan government will receive $5,000 per refugee they accept.

However, if deported to central Africa, the refugees' situation may be little better than if they were sent home. One Eritrean merchant described the predicament in no uncertain terms: "If I am forced to go to Rwanda, I will die," he said, according to the Jerusalem Post. "I know of people who went there — and we never heard from them again. They are given no rights and have no status."

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu boasted that Israel has already deported 20,000 African migrants, 4,000 of them in 2017. Having completed the intricate barrier along their Sinai border with Egypt, Netanyahu noted that no "infiltrators" had crossed the border in 2017 and that "The mission now is to deport the rest," referring to the 40,000 remaining refugees, according to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

Although the Israeli state's fear, according to the Washington Post, is that African migrants are mostly economic migrants whose numbers threaten its Jewish character, the case of Kimani, Abayudayas, and other African Jews calls this simple explanation into question.

In the wake of Kimani's deportation, Birthright, a non-profit NGO that sponsors "heritage trips" to Israel for young adults of Jewish heritage, has considered canceling a 10-day trip to Israel by 40 other members of the Abayudaya community due to fears that the tourists may face similar treatment, according to Haaretz. The trip was two years in the making.

However, Israel's troubles with African immigrants do not end with refugees and asylum seekers. Even legal immigrants and their descendants face increased hardship in Israel, including forced sterilization. A scandalous story by investigative journalist Gal Gabbay broke in early 2013 about Ethiopian immigrant women being forced to accept birth control treatments, or surreptitiously given them without their consent or even knowledge, as a condition of entering the country.

According to Forbes, some 130,000 Ethiopian Jews live in Israel, and the community experiences higher unemployment and poverty rates than the rest of the country's Jewish population. The experience of Ethiopian Jews is in many ways characteristic of that of Mizrahim in Israel — Jews who migrated from other parts of the Middle East — in general, according to the Times of Israel. Roughly half of Israelis are Mizrahi or part-Mizrahi, but they far outnumber Ashkenazi Israelis in prison, are far under-represented in academia, and are also generally poorer than Jews of European descent.

Prejudice against Mizrahim in Israeli culture persists as well; in March 2017, Netanyahu was forced to apologize after attributing a rash decision to his "Mizrahi gene" acting up, drawing widespread condemnation for what critics saw as perpetuation of a racist caricature, the Times of Israel reported at the time.