The crisis in relations between Poland and the EU seems to have escalated beyond what either side anticipated. On Wednesday, European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker was forced to emphasize that the bloc was "not at war with Poland," notwithstanding Brussels deployment of Article 7 of the Lisbon Treaty, which paves the way to sanctions, up to the deprivation of Poland's voting rights in the European Council, unless Warsaw mends its ways.

According to Prokudin and Ardaev, to Russian observers, the issue is simple: "Warsaw doesn't want to be an eternal periphery of the EU or any kind of 'second-class Europe'." Polish politicians, on the contrary, "intend to teach European bureaucrats about European and Christian values and, possibly, turn their own country into a new center of power." But for this to happen, Warsaw would have to take the seemingly unlikely step of making friends with their eastern neighbor, Russia.

"In Brussels there is still enormous hope, I won't say trust because that's already dead, that Poland will stay in the Union," Tusk added, hinting at Brussels' lack of illusions about the Law and Justice Party's real intentions.

The quarrel between Warsaw and Brussels began over Poland's judicial reforms, which the EC blasted as a violation of the rule of law and an opportunity for authorities to control the court system. The criticism quickly turned into threats of sanctions, up to and including deprivation of the right to vote in the European Council. Warsaw returned fire by rejecting directives from Brussels, Berlin and Paris, including on the resettlement of Middle Eastern refugees in their country.

Deja Vu

In Prokudin and Ardaev's view, the situation, "in some ways, looks similar to that of the 1980s, when Poland was part of another bloc – the Eastern Bloc." The journalists recalled that back in the 1970s, "the Soviet Union had to increase the amount of financial and material assistance to the 'fraternal' Polish People's Republic. Anti-communist sentiment in Polish society had not weakened, and the ruling Polish United Workers' Party responded by raising the standards of living of working people. Moscow agreed to the additional expense to maintain stability and prevent Warsaw from leaving its orbit."

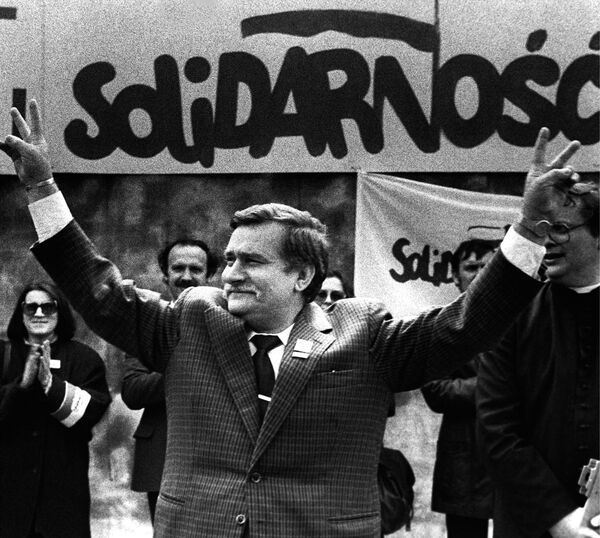

"In 1990, Solidarity leader Lech Walesa was elected president. Later it was reported that during his years of struggle against the communist regime, he actually cooperated with its state security organs. But the scandal led nowhere –Poles remain just as proud of Walesa as they are of the Polish pope."

"Soon after," Prokudin and Ardaev wrote, "the Warsaw Pact and the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON), the Soviet analogue of NATO and the EU, ceased to exist. What contributed to the collapse of the Eastern Bloc remains a question for historians, but one thing is clear: Poland was then at the forefront in the ranks of the 'saboteurs'."

Fast forward over a quarter century, and Poland is once again in opposition, this time to Brussels. Admittedly, observers note that this time, it's unlikely that Warsaw's conflict will the EU will be able to shake the bloc's foundations to their core. Yuri Solozobov, a fellow at the Moscow-based National Strategy Institute, recalled that as the powerful locomotives of the EU project, France and Germany will not simply allow Poland to leave the bloc, even if it wanted to.

"Warsaw is the largest recipient of EU assistance, and after 2020 will have to start repaying the funds it has received," the analyst noted. "Therefore, Brussels will not abandon Poland. As German experts joke, it's easier to change the Polish leadership than it is to leave the situation in Warsaw to chance. And in no one in Poland seriously wants to leave the EU anyway; everyone enjoys a comfortable life," he added.

The Brussels-Warsaw Crisis and Polish National Character

Furthermore, Solozobov said that the historical memory of Polish elites includes the fact that Poland too was once an empire, ruling over many different nations. Therefore, Warsaw feels it has a right to demand a special relationship, and to be spoken to on equal terms with any supranational institution.

Sergei Stankevich, Russian politician and political observer who lived in Poland for several years, echoed the notion that modern Polish political practice is rooted in history.

"In the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, deputies of the Sejm parliament had the principle of the liberum veto, or 'free veto', which allowed any deputy to stop debate," the observer recalled. "This has been preserved in the country's national character – that Poland has the right to veto." Furthermore, Stankevich noted, "there is the gentry's egoism and passion, summed up by the idea that 'I may die but I'll have my own way.' It's for this reason that Poland became the weak link in the world socialist system."

An Eye Towards the Future

According to Solozobov, the EU has postponed its eastward expansion, at least until it can 'digest' the Balkans. "European politicians are saying more and more often that Ukraine will not be allowed into the EU in the next 25-30 years. Accordingly, Poland will try use this period to actively work with the former territories of its Kresy [the so-called 'Borderlands' of the Polish Empire] – with an unsettled Ukraine, with a Lithuania losing its population, and a post-Lukashenko Belarus. This will not amount to a banal political expansion, but rather an effort to create a business environment that's beneficial for Poland."

For his part, Poland watcher Stanislav Stremidlovsky is convinced that as Warsaw continues to regain its great power ambitions, it will find its EU membership increasingly constraining. "Before Warsaw is the question of where to move on from here: Simply being a buffer zone between Moscow, Beijing and Brussels means stagnation. A Poland-Belarus-Russia bloc, in the form of a confederation, on the other hand, can become a real alternative over the next 10-15 years."

"The countries of Eastern Europe used to have well-established infrastructural ties with Russia. While it's true that many industrial ties have long since disintegrated, the example of the [Eurasian] Customs Union shows that such production cooperation and trade can quickly recover and even reach new levels. The future lies in a convergence of the economic structures of the EU and the Eurasian Union, and the reestablishment of transit routes between the economic super giants – Europe and China," the observer stressed.

But whatever happens next, Prokudin and Ardaev noted that for now, so long as new scandals between Warsaw and Moscow continue to drive a wedge in relations, it may be many years before the 'pragmatic relations' envisioned by Solozobov are realized.