In 1949, President Harry Truman signed off on National Security Council policy NSC 26/2, which stated in the event of a Soviet invasion of the Middle East, resources and facilities would be destroyed before the Red Army reached them. Dubbed "denial," the approach would see oil company employees primed to begin sabotaging and destroying their own facilities when given the green light by Washington.

While a US strategy, British Foreign Office documents indicate Whitehall was apprised of NSC 26/2, and enthusiastically backed the strategy, adding a corollary of their own — oil company employees would be assisted in their efforts by the military, including the Royal Air Force.

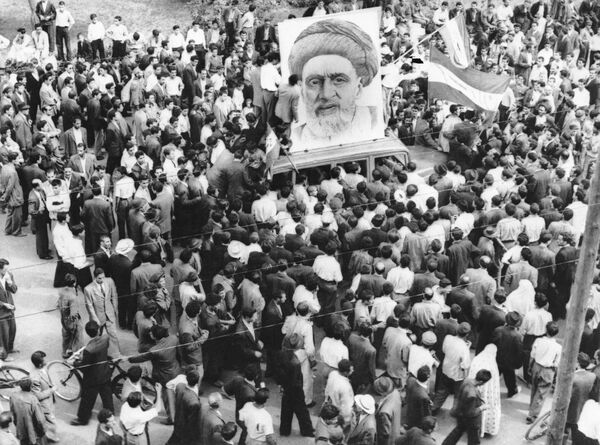

In the latter, even in the wake of the US/UK-led 1953 coup, which installed the pro-Western Shah in power and returned control of the Iranian oil industry back into British hands via British Petroleum, Tehran retained control of several facilities, and was in the process of building more.

British officials feared letting employees at the state-owned organizations in on the plot would significantly raise the risk of the "denial" plans leaking out — and it was thought unlikely the governments of either country, while allied with the UK, would agree to them in any event.

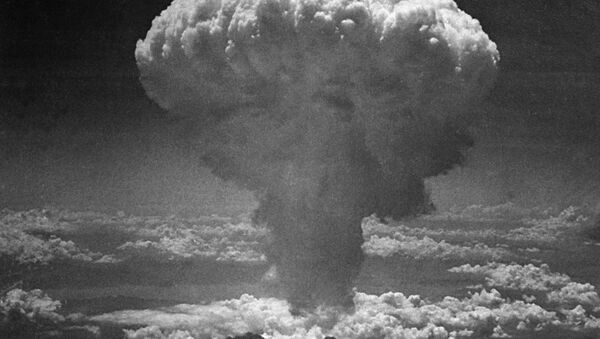

Nuclear Option

A potential resolution to the quandary was mooted in 1955. That year, the UK had begun to conduct nuclear weapons tests in the Australian outback — it was thought these armaments could be "most complete method of destroying oil installations" in Iran and Iraq, Britain's Joint Chiefs of Staff stated in a report.

While it's unclear from the files whether Washington was involved directly in these discussions, the Joint Chiefs certainly had official sanction to request the US use its own nuclear arsenal on Iran's oil fields in the event of a Soviet invasion of the country — a prospect discussed with US officials the next year. American nuclear action was judged "the only feasible means of oil denial" in Iran.

Although the files do not note any specific reaction to the suggestion, CIA operative George Prussing, who was assigned to work with Middle Eastern oil companies on "denial" plans, was sent to inspect Iran's oil fields and facilities, and investigative the feasibility of various "denial" proposals.

He judged "denial" via ground demolition was the best option, and nuclear destruction wouldn't be necessary. British officials happily noted that the large and growing volume of Americans working in Iran meant such a policy could be kept secret, and successfully executed if it came to it. Bill Otto, an employee of Saudi oil giant Aramco and a former bomb disposal expert, was sent to assist UK officials amend their denial plans for the region.

While nuclear weapons were off the table, the "denial" strategy subsequently grew in scope, to include a US refinery in Lebanon, a British facility in Egypt, and a then-unfinished refinery in Syria. The two countries also divided geographically responsibility for executing the strategy, with the US taking responsibility for the Kuwait Neutral Zone, and the UK refineries and pipelines in Israel and Turkey.

Moreover, he suggested the demolition training programs oil company employees conducted represented a security risk, and made public exposure much more likely. As a result, a new policy — NSC 5714 — was minted, which removed all civilian involvement and ended collaboration with oil firms, instead leaving the task of scuttling oil facilities solely to military forces, and only if they were taken over by the Red Army, or local military force.

Concurrently, the British and Americans both independently forged supplementary policies for protecting their low-cost access to Middle East oil. London pivoted towards pre-emptively protecting key oil installations in the Gulf from "Egyptian subversion," while Washington primed troops to tackle Arab nationalist elements in key oil-producing countries.

Historical Precedents

What ultimately became of these plans — and whether and how Middle East rulers complied with them — is not clear from the declassified files. The last mention of the "denial" strategy in US memoranda falls in 1963, when a John F. Kennedy Administration staffer asks the State Department whether NSC 5714 was still government policy or had been replaced. The Department's response, if there was one, isn't publicly available.

As a result, it's uncertain when the policy ended, or whether it did at all — NSC 5714 may have been amended and refined, or revoked outright, in the decades since.

However, it was not the first time the West had planned a nuclear "first strike" on the Soviet Union. In 1945, as World War II in Europe was nearing its end, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill asked his military chiefs to prepare a secret war plan — "Operation Unthinkable" — that would see the Western allies execute total war on the Soviet Union in Central and Eastern Europe, before marching on to the Soviet Union itself.

Force totals in Europe were highly unequal — the US and UK had just under four million men in Europe when Germany surrendered, the majority of which were Americans who would soon be transferred to the Pacific to fight Japan, and the Red Army numbered over 11 million. To make up the shortfall, captured Nazis would be conscripted into the West's ranks — and Soviet forces would be peppered with atomic bombs.

As luck would have it, British planners concluded the plan's chances of success were "quite impossible" — especially as they depended entirely on US acquiescence and support.

Nonetheless, Churchill presented President Truman with the plan, although noted it sketched out a "purely hypothetical contingency." Truman made clear the US would play no part in Operation Unthinkable, and the plan was dropped.

Targeted cities included Moscow and Leningrad, which would have 175 and 145 "designated ground zeros" respectively.

The nuclear weapons would be delivered by aircraft such as the B-47 — based in the UK, Morocco and Spain — and B-52.