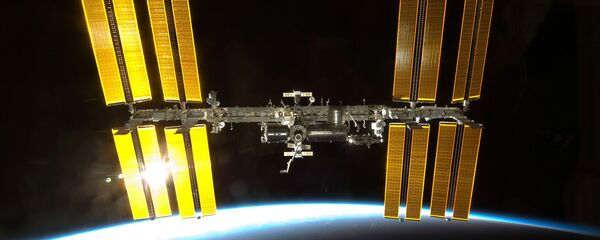

According to the Washington Post report, Trump wants to turn the station into a "kind of orbiting real estate venture run not by the government, but by private industry." The White House reportedly plans to request $150 million "to enable the development and maturation of commercial entities and capabilities, which will ensure that commercial successors to the station are operational when they are needed."

The ISS costs up to $4 billion a year and the US federal government has already spent nearly $100 billion over more than a decade to keep it up and running, according to Popular Mechanics.

Talking to Radio Sputnik, von der Dunk noted that a proper reaction to Trump's statement should be based on a precise understanding of the word "privatization." He noted that the ISS has been built based on a number of international treaties and one cannot simply dodge these agreements, let alone attempt to privatize the whole station.

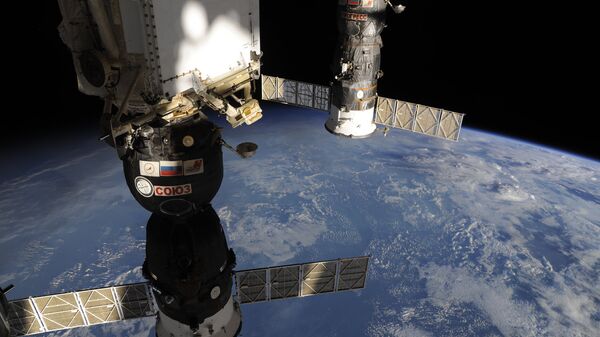

"For starters, part of the space station is actually not American, but Russian, European, Canadian and Japanese," he said.

If, instead of NASA, a private contractor is to take over the US-owned parts of the ISS, this would be a "fundamental change" that "would at least require renegotiation of the space station agreement," says von der Dunk.

"It's not totally impossible, but it does require a set of fundamental steps," he added.

However, the idea that the US as a state would one day stop participating in the fate of the ISS actually emerged under Trump's predecessor, Barack Obama. Concerns that the US would cut funding of its part of the station made other partners consider how to deal with that possibility, von der Dunk says. For Europeans, it is extremely desirable that the US continues to invest in the station. If the US government decided to abandon this venture, switching to the private sector would be a welcome option, he explains.

Thus, von der Dunk explains, even if some space company inflicts damage to the ISS, it will be the US of A that will pay the space station compensation.

According to von der Dunk, this would require the state to set up a licensing system that would ensure that those private company will, in their turn, pay fees to the US Treasury. With such a system in place, the operation of private contractors on the ISS could actually be possible, von der Dunk concludes.