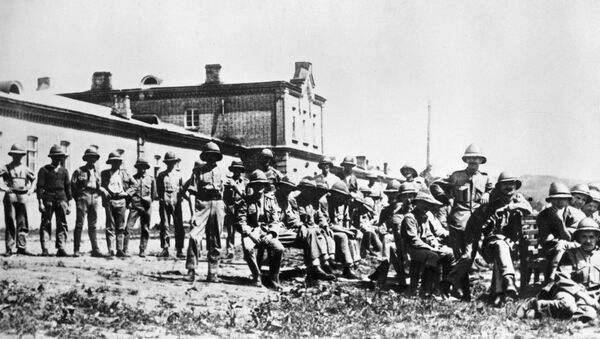

In March 1918 the Bolshevik government signed a peace treaty with Germany, as they had promised to the nation exhausted by four years of the devastating and senseless WWI. The Russian Revolution was triggered by the overwhelming public desire for peace. The war-weary Russian army simply could not carry on fighting. Britain and France immediately accused Russia of betraying the Allied cause and sent in their troops. In a show of "solidarity" reminiscent of today, a dozen Anglo-French allies took part in the armed intervention in Russia. The official excuse was to keep the Eastern front against Germany and protect the Russian war materiel from falling into German hands.

The map of foreign military intervention in Russia in 1918-1919.

In reality, the British, the French, the Americans, the Japanese and many others fought the locals, engaging in "frolics" and "high handed behaviour," according to British government papers.

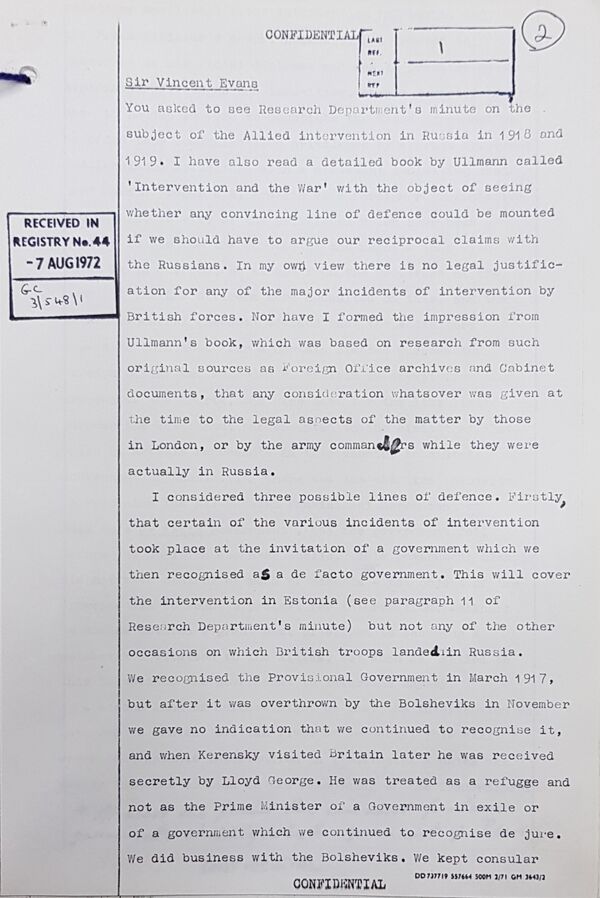

The legality of their action under international law was not considered until 1972 when the British government, locked in a dispute with Moscow over mutual debts, sought advice from a Foreign Office legal counselor, Eileen Denza. The advice was damning of London's actions and was kept under wraps for a long time.

"In my own view there is no legal justification for any of the major incidents of intervention by British forces," Ms. Denza wrote in her paper. "Nor have I formed an impression from … research from such original sources as Foreign Office archives and Cabinet documents that any consideration whatsoever was given at the time to the legal aspects of the matter by those in London, or by the army commanders while they were actually in Russia."

Ms. Denza had explored possible avenues for defending the British intervention but failed to find any convincing arguments.

Argument 1. Certain incidents of intervention took place at the invitation of a Russian government which Britain then recognized as a de facto government.

This, Ms. Denza said, would cover the intervention in Estonia [which Britain helped break away from Russia — NG] but not any of the other occasions on which British troops landed in Russia. Britain did recognize the Russian Provisional government after the overthrow of the Tsar in March 1917, but after it was overthrown by the Bolsheviks in November Britain gave no indication that she continued to recognize it. Indeed, when its premier Kerensky visited Britain later he was treated as a refugee, and not as a prime minister of a government in exile or of a government which London continued to recognize de jure.

"We did business with the Bolsheviks," Ms. Denza reminded the British government. "We kept consular relations until well after intervention had begun, and the Prime Minister's envoy, Bruce Lockhart, was … accorded diplomatic privileges and immunities [which he abused — NG]".

Initially Lockhart devoted a great deal of effort to securing a Bolshevik invitation to the Allies to intervene, but when he failed in this he advised the British government to intervene anyway. He started plotting for the overthrow of the Bolsheviks, and channeled his energy into persuading the reluctant US President Woodrow Wilson to support the British and Japanese intervention in the North and Far East of Russia.

Argument 2. The intervention was intended to protect British lives and property.

There was no British community in Russia to speak of.

"The question of defence of British property was never raised or put forward at any stage," wrote the FCO legal counselor, "and it had always been clearly understood that it was intervention which led the Bolsheviks (who began by being friendly to Britain) to take much more extremist measures against property generally and to adopt the position that no compensation would ever be paid to the Allies in respect of their expropriated property, since it was the necessity caused by external pressures and Allied intervention which had made it necessary to seize foreign property on such a scale."

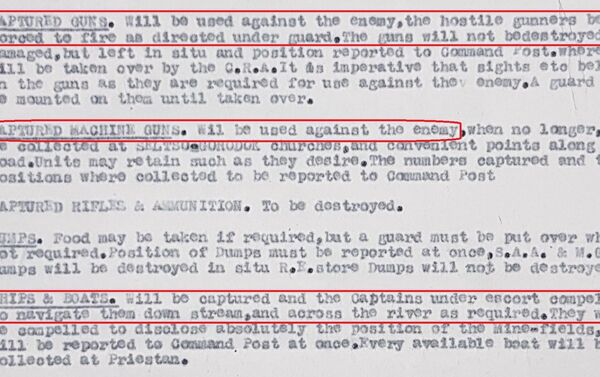

Argument 3. The intervention was justifiable as an act of military necessity, or self-defense, in order to protect the Allied military position in the east after Russia's withdrawal from the war following the peace treaty of Brest-Litovsk signed with Germany in March 1918.

Britain at the time made a great deal in public that the motive for intervention was related entirely to the conduct of the war, and that there was no intention to intervene in the domestic affairs of Russia. However, once they arrived in Russia, the British and other Allied forces "did not limit their actions to cutting off supplies to the Germans," wrote Ms. Denza. "They did not confine themselves to supporting factions which had clearly stated that once in power they would bring Russia back into the war."

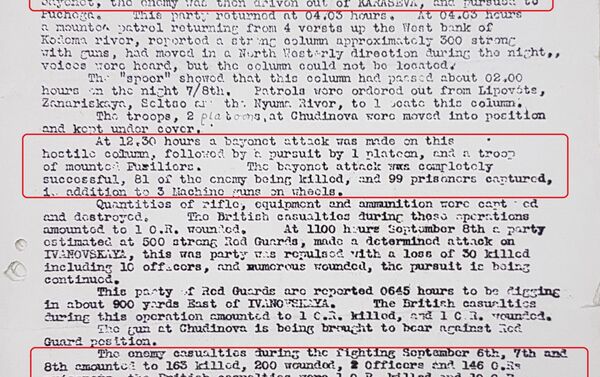

"In the main the commanders in the field seem to have gone off on frolics of their own with very little clear political coordination." [Those "frolics" included bayoneting the locals to death, and forcing captured Russian gunners to turn their cannons on their compatriots, according to British commanders' combat logs held by the National Archives — NG]

When large-scale intervention began in the summer of 1918 Britain withdrew its embryonic diplomatic and consular mission from Russia [thereby implying it was an invasion rather than intervention — NG].

Most important of all, Ms. Denza wrote, the intervention did not cease with the surrender of Germany in November 1918. Indeed the military justification for intervention, which could have existed during the many months when plans for intervention were being made and discussed "virtually ceased to exist very soon after our troops first went in [Russia — NG] in substantial numbers [shortly before Armistice — NG]."

Overall, the FCO legal counselor said, the British and Allied intervention in Russia painted "such a damning picture."

"The immediate effect of the intervention was to prolong a bloody civil war," wrote American historian James W Loewen, "thereby costing thousands of additional lives and wreaking enormous destruction on an already battered society."

During the Anglo-Soviet debt negotiations in 1972-1973 this destruction was estimated to be between two and four billion pounds.

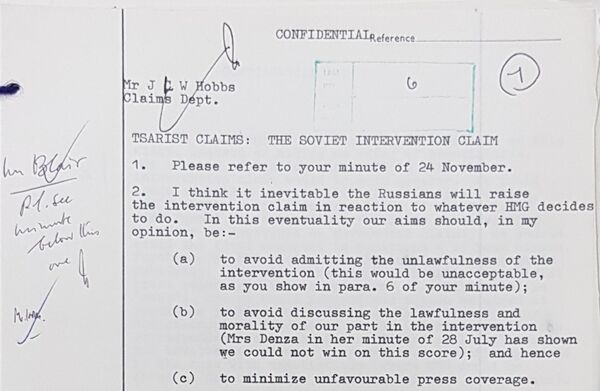

British government papers of the time record a flurry of Whitehall discussions on how to avoid admitting any liability for the damages caused by the unlawful intervention. As one note put it:

"I think it inevitable the Russians will raise the intervention claim in reaction to whatever HMG decides to do" [e.g., expropriate Russian gold held by Britain in payment for Russian debt — NG].

In this eventuality our aims should be:

(a) To avoid admitting the unlawfulness of the intervention (this would be unacceptable)

(b) To avoid discussing the lawfulness and morality of our part in the intervention (Mrs. Denza in her minute of 28 July has shown we could not win on this score); and hence

(c) To minimize unfavourable press coverage.

Whatever the press coverage, the intervention did create very unfavorable attitudes towards Britain in Soviet Russia.

In 1921 a British Parliamentary Committee produced a report which included the following perceptive passage:

"There is evidence to show that, up to the time of military intervention the majority of the Russian intellectuals were well disposed towards the Allies, and more especially to Great Britain, but that later the attitude of the Russian people towards the Allies became characterised by indifference, distrust and antipathy." [Report (Political and Economic) of the Committee to Collect Information on Russia; (Russia (No.1), 1921, Cmd. 1240]

American Historian William Henry Chamberlin, who was the Moscow correspondent of The Christian Science Monitor in the 1920-30s, wrote that the consequences of the intervention "were to poison East-West relations forever after, to contribute significantly to the origins of World War II and the later Cold War, and to fix patterns of suspicion and hatred on both sides which even today threaten worse catastrophes in time to come."

God forbid his prophecy comes true…

The views and opinions expressed by the contributor do not necessarily reflect those of Sputnik.