The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) in Colorado has alarmed the global community with their discovery of increased emissions of an ozone-depleting chemical, whose production was banned worldwide nearly ten years ago. The gas could delay recovery of the ozone layer for decades.

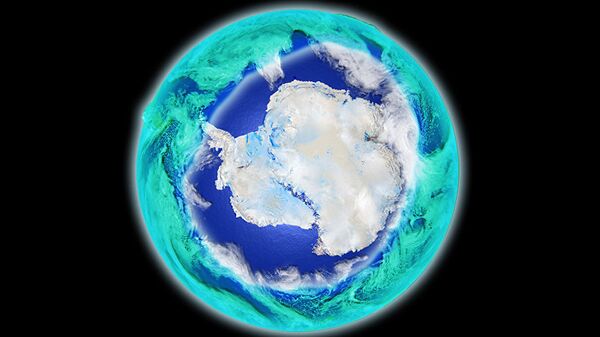

According to the new study, published in the Nature magazine, unreported production of the second most damaging gas CFC-11, marketed as Freon and responsible with other chemicals from the CFC family for a giant hole in the Earth’s UV-shield over the Antarctic, is located somewhere in eastern Asia.

"We're raising a flag to the global community to say, 'This is what's going on, and it is taking us away from timely recovery from ozone depletion.' Further work is needed to figure out exactly why emissions of CFC-11 are increasing and if something can be done about it soon,” research leading author Stephen Montzka said.

Widely used for production sprays, foams, solvents and refrigerants since the 1930s, CFC chemicals were banned internationally in 2010 according to the Montreal Protocol, after scientists found out that CFCs release chlorine molecules into the atmosphere, “eating” ozone. As all countries in the world agreed to stall production of ozone damaging gases, the remaining stores were expected to be released into the atmosphere and subsequently diminish, and the ozone hole was expected to recover.

READ MORE: Ozone Depletion Montreal Protocol ‘Prevented Ecological Catastrophe' – Expert

Scientists have carefully monitored the progress and measured chemical compound of the planet’s atmosphere. According to NOAA’s analysis, Freon average annual emissions jumped by 25% between 2014 and 2016 in comparison to 2002-2012 period, before the global ban was agreed.

The scientists had to do detective work to find out the culprit behind the increase in emissions. Options that there have been changes to how the atmosphere destroys the chemicals, that the CFC was released from older materials or produced as a by-product of other chemical manufacture, were ruled out as the increase of emissions was too high. So the team came to the conclusion that someone is newly producing the chemicals.

Evidence led the group to eastern Asia; however, the exact location still needs to be investigated. Incidentally less harmful replacements are more expensive to produce.

Montzka is calling for prompt action, as the damage will be minor only if the culprit is detected and shut down soon. Otherwise, if the emissions continue to increase, the ozone layer’s recovery is expected to be delayed by decades.

Head of UN Environment Erik Solheim, cited by The Guardian newspaper, shares the scholar’s concern: “If these emissions continue unabated, they have the potential to slow down the recovery of the ozone layer. It’s therefore critical that we identify the precise causes of these emissions and take the necessary action.”