Writing in The Guardian's Comment is Free section, NATO's 13th Secretary General warns readers the divisions between the US and its European allies that have arisen under Donald Trump's Presidency must be resolved — for the sake of the world.

"The ties that bind us are under strain. There are real differences between the US and other allies over issues such as trade, climate change and the Iran nuclear agreement. These disagreements are real and won't disappear overnight. Nowhere is it written in stone the transatlantic bond will always thrive. That doesn't, however, mean that its breakdown is inevitable. We can maintain it, and all the mutual benefits we derive from it," Stoltenberg said.

Differences of Opinion

First, Stoltenberg notes "differences of opinion are nothing new" between the US and Europe, listing three key examples — the Suez crisis in 1956, France's withdrawal from NATO in 1966, and the Iraq War in 2003 — major fractures in North Atlantic unity which he suggests were overcome by an ability "to unite around our common goal: standing together and protecting each other." Precursory analysis reveals a rather different reason behind the resolution in each case.

The Suez crisis, in which France and Britain attempted to regain control of the Suez Canal and remove Egyptian President Abdel Nasser from power, nearly exploded into direct armed conflict between the US and its two leading NATO allies after Admiral Arleigh Burke proposed "blasting the hell out of" British and French ships to halt the operation quite literally dead in its tracks. In the event, President Dwight D. Eisenhower forced the British to withdraw by threatening to sell his government's Sterling Bond holdings, and in turn cripple the country's economy.

It has been suggested the US Central Intelligence Agency even went so far as to hatch assassination plots to take out de Gaulle.

The Iraq War saw the US not only disregard the views of most of its major European and NATO allies, but disparage them too, in pursuit of the internationally unpopular intervention. Then-Defense chief Donald Rumsfeld repeatedly referred to France, Germany and other dissenters as "old Europe", while the more supportive states of Eastern and Central Europe were "new" — but in the event, neither Europe committed troops to the effort.

In essence, each "difference of opinion" cited by Stoltenberg ended in the same fashion — with Washington prevailing, and the needs and interests of its European allies crushed, by any means necessary.

Sound and Fury

Stoltenberg's second and third reasons exhibit a similar tendency for omission and distortion. He records how after the Cold War, the US and Canada "gradually reduced" their presence in Europe, and European allies cut defense spending, as part of a so-called "peace dividend".

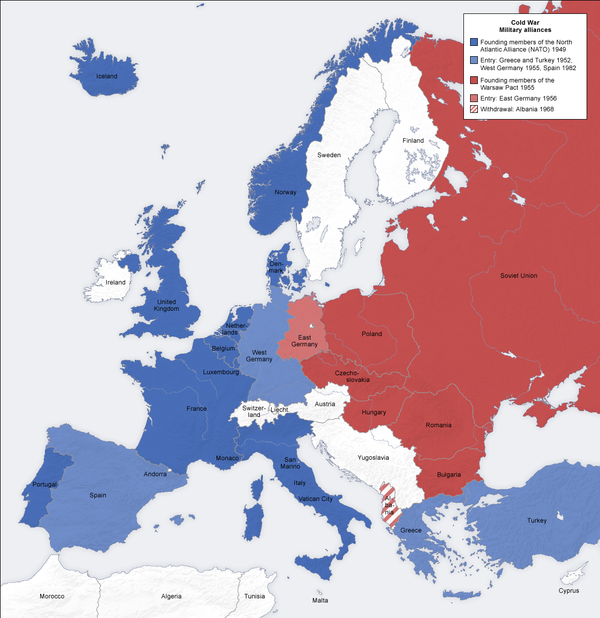

Moreover, the end of the Cold War demonstrated Russia's willingness to cooperate fruitfully with Europe and the US — a willingness disregarded and disrespected by NATO. In 1990, James Baker, then-secretary of state, visited Moscow and informed Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev the US wished for Germany to be reunified. In return for not opposing the move, Baker promised the alliance would not expand "one inch eastwards" towards the Soviet Union's borders. Gorbachev accepted the offer — and this pledge was subsequently reiterated by then-German Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher, who said in a January 31, 1990 speech in Tutzing, Bavaria there would not be "an expansion of NATO territory to the east, in other words, closer to the borders of the Soviet Union."

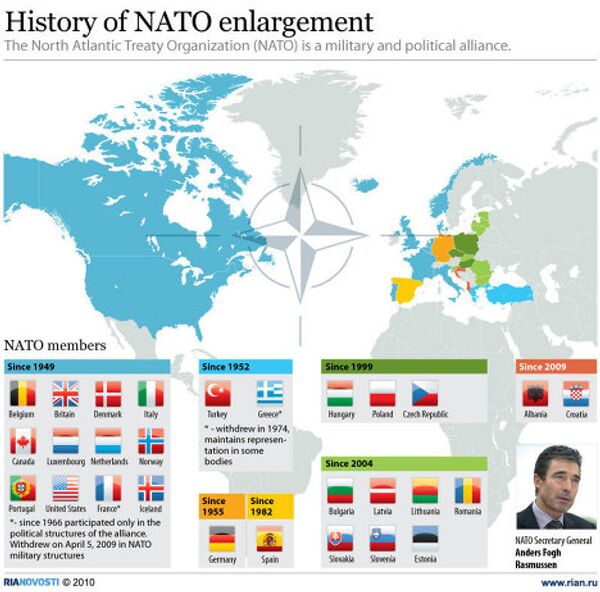

These apparent cast-iron pledges would not endure long — in 1999, much began expanding eastwards, by a great many inches, with three former Warsaw Pact countries (Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Poland) joining the alliance. This enlargement was opposed at the time by George Kennan — previously a committed "cold warrior" and key figure in the creation of NATO — who predicted it would precipitate the start of a 'new Cold War'.

"The Russians will gradually react quite adversely and it will affect their policies. It's a tragic mistake. There was no reason for this whatsoever. No one was threatening anybody else. This expansion would make the Founding Fathers of this country turn over in their graves. Our differences in the Cold War were with the Soviet Communists. This has been my life, and it pains me to see it so screwed up in the end," Kennan said.

He added there would "of course" be a negative reaction from Russia, and then "NATO expanders will say 'we always told you that is how the Russians are' — but this is just wrong.'' Kennan's warnings have been ignored ever since — in 2004, more former Warsaw Pact members, along with former states of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia (Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia) were admitted. As of June 2018, NATO stands 13 members larger than it did in 1990, 10 of which formerly comprised the Warsaw Pact, and three of which formed part of the former Yugoslavia.

Transatlantic Disunity

Fittingly, Stoltenberg cites modern Russia — which he claims "has used force against its neighbours, tries to meddle in our domestic affairs, and seems to have no qualms about using military-grade nerve agents on our streets," all common, baseless allegations unsupported by concrete evidence of any kind — as a key reason for continuing transatlantic unity. That such transatlantic unity, in the form of NATO, may be a destabilizing factor in international cooperation, peace and security goes entirely unconsidered by the alliance chief.

However, statements made elsewhere in Stoltenberg's article contradict the notion of dissension in the ranks of NATO — he proudly boasts that since coming to office, the Trump administration has increased funding for the US presence in Europe by 40 percent, and new US armored tank brigades have been dispatched to the continent in their droves. In turn, European allies "are stepping up too" — spending billions more on defense and "taking responsibility for Euro-Atlantic security alongside their North American allies."

With more money being pumped into NATO than ever on all sides, and European states large and small increasingly involved in the US' military activities in the region and beyond, it's uncertain what Stoltenberg is quite so worried about. Irrespective of political squabbles both minor and major between the heads of NATO states, ever-worsening relations between the West and Russia, and rising internal opposition in many countries to membership, the military alliance is set to endure, and fulfil its paradoxical purpose of "managing the security risks created by its existence."