Pro-military news site Forces Network has used the findings as a springboard for the launch of a DVD — 100 Years of the RAF - ostensibly intended to "help the British public learn more about the history of the Royal Air Force" — however, it's doubtful the film will contain any references whatsoever to the many controversial, shadowy and cataclysmic incidents that have frequently blighted the RAF over the course of its century-long existence.

Foaming at the Wings

In 2008, an inquest ruled 10 RAF servicemen ruled were unlawfully killed when their Hercules aircraft was shot down in Iraq in 2005, with investigators concluding "serious systemic failures" had deprived victims of the "opportunity for survival".

The failure of both the Ministry of Defense (MoD) and RAF to fit Hercules planes with explosion-suppressant foam (ESF) constituted a "serious failure" — and the lives of the men aboard 47 Squadron Special Forces flight XV179 could have been saved had their aircraft been equipped with the safety provision — coroner David Masters ruled.

The inquest was stonewalled by both MoD and US military officials, with Masters stating the investigation had been "plagued by an inability to retrieve documents" relating to key RAF decisions prior to the tragedy — he also said the US' refusal to cooperate with the inquest was "difficult to comprehend", given US servicemen were the only Allied witnesses to the crash. US officials refused to authorise interviews with the officers, and they were not permitted to attend the inquest.

Despite this, available documents revealed a 2002 military research document strongly advised Hercules planes be fitted with ESF, a recommendation reiterated in a 2003 Tactical Analysis Team report. Moreover, it was clear Hercules crews weren't apprised of the danger they were in, information that might have motivated them to alter their flying tactics.

Weather Weapons

Declassified records show from 1949 to 1955, under the auspices of ‘Operation Cumulus', the RAF released various substances — including dry ice, silver iodide and salt — into the UK's atmosphere at high altitudes in order to induce rain. Using chemicals supplied by Imperial Chemical Industries, scientists from around the world were involved in the experiments, including specialists from the RAF's meteorological research base at Farnborough.

Minutes from a November 3 1953 air ministry meeting show why UK government were interested in increasing rain and snow by artificial means in order to "[bog] down enemy movement", "increment the water flow in rivers and streams to hinder or stop enemy crossings", and clear fog from airfields. The documents also suggest rainmaking had the potential to "explode an atomic weapon in a seeded storm system or cloud," producing "a far wider area of radioactive contamination than in a normal atomic explosion".

These secret weather weaponization experiments persisted three years after they produced the worst recorded flood in British history — the Lynmouth disaster of 1952, in Devon, south-west England. In all, 35 were killed when a torrent of 90 million tons of water and thousands of tons of rock poured off saturated Exmoor and into the village below, destroying homes, bridges, shops and hotels.

One of the Operation's many navigators, Group Captain John Hart, told the BBC many years later about how the experiments would run.

"We flew straight through the top of the cloud, poured dry ice down. We flew down to see if any rain came out of the cloud — it did about 30 minutes later, and we all cheered," he said.

Similar elation was evident among experiment participants after the Lynmouth operation — but when the BBC reported the scale of the damage their clandestine activities had inflicted on the town and its inhabitants, glee turned to panic — it was uncertain which government department would be charged with rebuilding the area, and compensating inhabitants. Eventually, it was decided to simply deny any external role in precipitating the incident, and indeed any British government interest in weather control.

In 2001, the British Geological Survey examined soil sediments in and around Lynmouth to see if any silver or iodide residues remained — silver residue was discovered in the catchment waters of the river Lyn, representing a potentially significant health hazard.

Inside Job?

On June 2 1994, the RAF suffered its worst peacetime disaster when one of the Force's Chinook helicopter crashed on the Mull of Kintyre, Scotland — all on board, including 25 passengers and four crew, were killed. Among the former contingent were almost all the UK's senior Northern Ireland intelligence experts — 10 senior Royal Ulster Constabulary intelligence officers, nine army intelligence officers, and six MI5 officers.

It is perhaps this lack of official clarity that has caused many alternative theories to abound in the years since. For example, British aviation expert Walter Kennedy, who independently investigated the crash over the course of 17 years, suggests the crash may have been an ‘inside job'.

"All official inquiries have totally misrepresented what happened. There've been so many lies, misrepresentations and obfuscations. Anyone with an avionics background who looks into this will see that the official account is seriously flawed. Do I think the Chinook was sabotaged? Absolutely," he said in 2011.

Kennedy's investigation into the Chinook crash was based on flight data disclosed but not investigated by official inquiries, close inspection of the crash site, interviews with locals, and sensitive information handed over by various insider sources. He concluded the Chinook was not downed by bad weather, but by "avoiding hitting a fixed, fuzzy obstacle they needed or wanted to get close to for whatever reason."

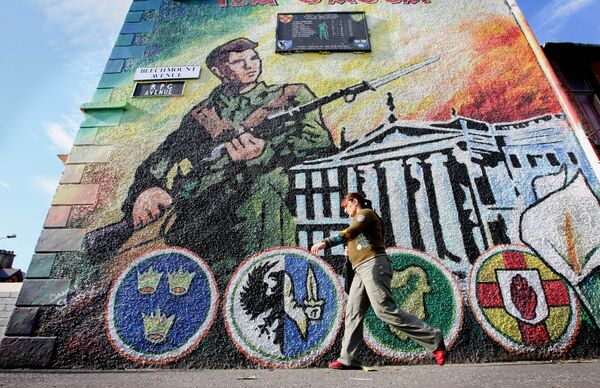

The wider political milieu of the time adds further fuel to conspiratorial speculation. In the summer of 1994, the UK government was conducting — both overtly and covertly — negotiations with Irish republican groups in an attempt to facilitate a ‘peace process', and a political settlement to the conflict in Northern Ireland that had raged for almost three decades.

However, convincing the militant elements of the republican movement to put down arms was difficult — two prior ceasefires brokered in the 1970s had been abused by the British government, with military and intelligence operatives instead using the opportunity to battle the IRA via covert methods. Many key figures suspected another ceasefire would be similarly violated, and there was indeed strong resistance to London's proposals among top British military and intelligence officials — some of whom were on the doomed helicopter.

The diaries of an RUC officer killed in the crash, Ian Phoenix, were published in 1996 — they made clear he believed the IRA could be militarily defeated if Whitehall let he and his colleagues "do their job". Several of the individuals on board were also involved in highly controversial, bloody episodes during the ‘Troubles', including ‘Shoot to Kill' operations in the early 80s.

"The loss of such senior intelligence personalities probably ensured the political case for a peace process to go ahead despite recent successes against the Provisional IRA and loyalist paramilitaries," he said in 2000.

Nearly three months after the crash, on August 31 1994, the IRA announced the ceasefire, calling for a "complete cessation of armed struggle" in Northern Ireland. The move would eventually pave the way for the 1998 Good Friday Agreement.