A new study by Canadian astronomer Anne Archibald, a postdoctoral researcher at the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy, has measured a special kind of neutron star called a pulsar as it was making its way — or more accurately “falling” — toward another star. The researchers afterwards compared the exact measurements with those of a much lighter white dwarf star falling toward the same star and found practically no difference in their response to the star's gravity.

"What we do see we're pretty sure is completely consistent with general relativity," CBC quoted Ingrid Stairs as saying. Stairs is an astronomy professor at the University of British Columbia who co-authored the study, which was published Friday in Nature.

Einstein's theory describes gravity as curves in space-time relations that objects make as they descend or fall. In space, gravity and “falling” takes the form of stars, planets and moons going around one another.

Magic Trio

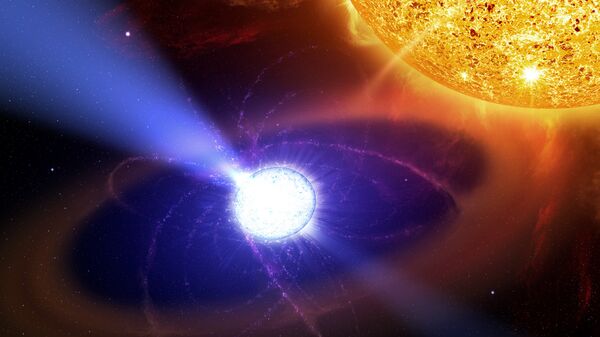

A unique trio of stars first spotted by Stairs and some colleagues in 2012 essentially made the above-mentioned survey possible. The trio notably features a special kind of neutron star making rounds in a triple star system. The neutron star featured in this study is a millisecond pulsar, a neutron star that spins at a record speed — 366 times per second. What’s even more extraordinary is that the pulsar is orbiting two other stars, and a large white dwarf orbits them both.

"For a triple system to survive a supernova that forms a pulsar is really remarkable," Archibald said.

The system is called PSR J0337+1715 and is located about 4,200 light-years away in the constellation Taurus. According to the researchers, it could be used to perform unique gravity tests in the future.

"This has allowed us to go beyond what is possible in the solar system," Stairs said, adding that they feel "pretty much excited."