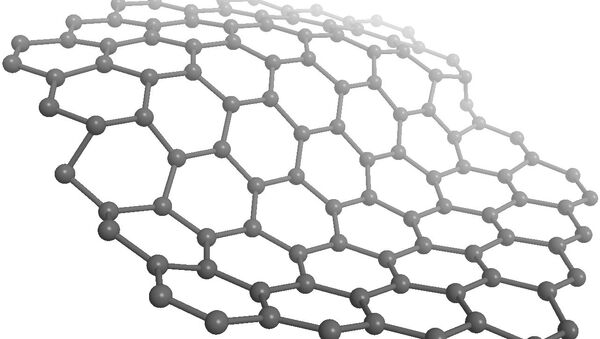

Musicians tighten their instrument strings to obtain a certain sound quality. A similar method is used in carbon nanoelectronics — scientists use deformed carbon nanotubes to make wires, diodes, transistors, and many other components.

However, these carbon "strings" are a hundred thousand times thinner than a human hair, so scientists need to develop complicated methods to strain them.

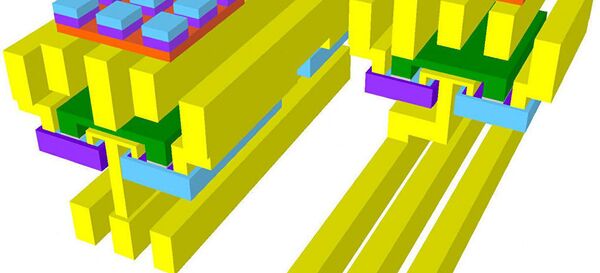

"The existing methods are aimed at creating single samples of strained nanotubes; this makes them too expensive for industrial applications," said Konstantin Katin, assistant professor at MEPhI's Institute of Nanoengineering in Electronics, Spintronics, and Photonics. "This is why we came up with an alternative designed for large production volumes that involves depositing carbon nanotubes on the supporting wafer pre-implanted with hydrogen and helium ions."

READ MORE: Russian Scientists Prove Eco-Toxicity of Silver Nanoparticles

Upon thermal annealing, these ions turn into gas-filled platelets that grow to form a blister on the surface of the wafer, Katin explained. This blister causes the deformation of the nanotube. By changing the temperature, scientists can control the size of the blister and, therefore, the deformation of the nanostructure.

"Our method is applicable to not just carbon nanostructures, but to a wide range of nanostructures," said another Institute employee, assistant professor Mikhail Maslov. "The electronic properties of most low-dimensional systems change with the application of tensile strain."

Today, the researchers are testing the efficiency of hydrogen blisters on other materials (such as graphene flakes and carbon peas) and plan to patent their developments.