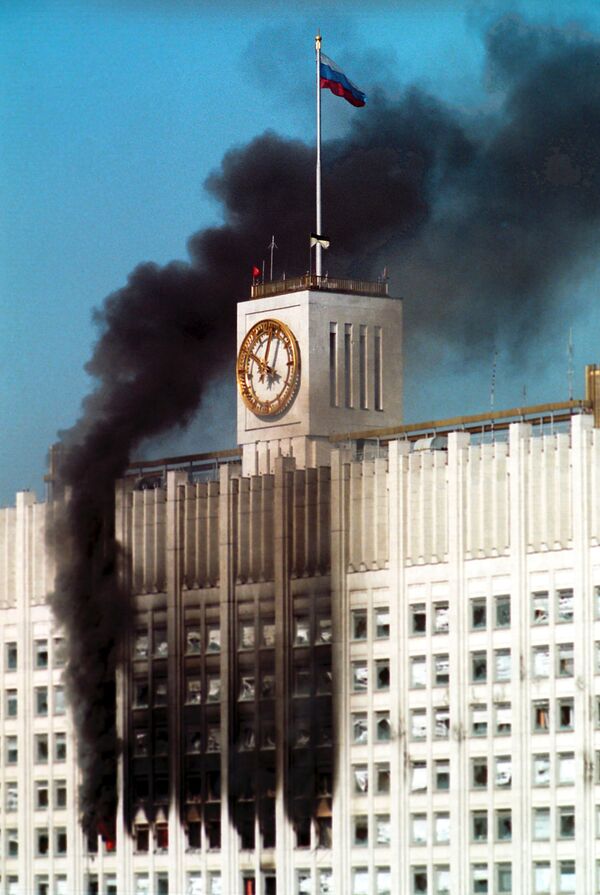

The October 1993 crisis followed a political standoff between Russia’s former president Boris Yeltsin and his opponents, led by Vice President Alexander Rutskoi and Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet Ruslan Khasbulatov. After Boris Yeltsin dissolved the country’s parliament in September, his opponents declared his decision illegal and proclaimed Rutskoi as acting president. The political row escalated into street fights in central Moscow, the shelling of the White House and the storming of the TV Center. At least 160 were killed.

Fred Weir, a Moscow Bureau Chief for the Boston-based daily The Christian Science Monitor, was one of the foreign journalists working in Moscow in October 1993, covering the events that unfolded during this turbulent month.

READ MORE: 'Black October' 25th Anniversary: Participants Regret Tank Deployment in Moscow

Sputnik: How much were you involved in covering the events that led to the White House assault?

Fred Weir: I covered the entire thing; from the decree that Boris Yeltsin issued I think sometime in September, dissolving the parliament through the long siege. I think it was two weeks or so, a virtual military siege of the White House by mostly Interior Ministry forces. Then, on October 3rd a huge demonstration which gathered in October Square marched along the Sadovoye Koltso to the White House and it broke the siege, broke the siege wide open and protesters poured into the White House. The Congress of People’s Deputies was convened. That was in those days, under that Constitution the supreme parliamentary forum and the Supreme Soviet was like a smaller body that met regularly and was taken from the members of the Congress of People’s Deputies. In that moment it really seemed like the protesters, the parliament had won. Unfortunately, Vice President Rutskoi gathered people together and set off to take the radio tower Ostankino in a military fashion.

Sputnik: You’ve basically retraced the events but could you tell us how you personally learned that the assault had started and where you were?

Fred Weir: First of all, I was there on October 3, I was with that big demonstration that broke into the White House and I was there in the White House when I talked about Rutskoi going out and organizing people to go and attack Ostankino. I witnessed that myself. Then I returned early the next morning to the White House. I couldn’t get in because at that point it was under siege. I was personally deeply involved, as an observer, in those events. I was in the case of hearing about it and coming over to see. I covered the whole thing from start to finish.

Sputnik: What was actually happening on the ground? Obviously, you saw the assault itself; did you manage to speak to, perhaps, some of the people – the eyewitnesses, the participants during the standoff?

Fred Weir: I wasn’t in the White House as it was being shelled; some of my colleagues were. I had some colleagues who had just spent the night there and they got great stories from inside. It was on October 3 when I was there inside the White House. Everybody was gathering, they were passing out arms, they were expecting an attack. There was apparently a large arsenal of small arms in the basement of the White House in those days, so that every people’s deputy pretty much had a Kalashnikov. There was a real feeling of a civil war that thankfully has never returned to Russia. It really was a clash of futures, what kind of idea of Russia that people wanted. And it’s easy to forget that now and see it as a sort of some legal dispute or something it wasn’t. It was really deep and the direction that Russia took was clearly decided by the military outcome of that. But on the streets and during the demonstration – it was huge, it was enormous. It was much more than the 10,000 people normally reported, that came and smashed the siege of the White House.

Sputnik: What kind of direction were you getting from HQ regarding your job?

Fred Weir: In those days there were no cell phones, there was no regular contact with my office. I had to go home to my own office and contact them by email or telephone. So, I wasn’t getting any direction. I was going and doing whatever I could and that was to observe the events, to talk to people and I did my best. New technologies have made it possible to cover things right on the spot by the second [there’s] instant feedback. In 1993 we didn’t have that.

Sputnik: What kind of an outcome did you expect during the crisis? I’m guessing that you actually mentioned that knowing that Rutskoi was a military man and when he led that assault I suppose you had the impression that that’s when things might get violent and take a different turn?

Fred Weir: I’m an old-fashioned peacenik myself and I had great forebodings at that point when I saw Rutskoi mobilizing people out in the courtyard because whole crowds had gathered right there in the courtyard of the White House.

He was lining them up and getting them in military ranks; they were being issued weapons. I had tremendous forebodings about that. In my own mind and in my own heart I sort of sided with the parliament and I wrote that way too, you can look it up. You know, journalists, all our sins are in black and white. I was one of the few who raised a lot of questions about the Yeltsin narrative, about a communist parliament standing in the way of democracy and reform, but anyway, that is beside the point. I did hope for a peaceful outcome. And for a few hours there on October 3 it looked like there would be. The Congress of People’s Deputies which was the supreme legislative body of the country would pass some new laws and create a new paradigm of power in Russia, and that civil war would be averted. Instead, we did have a civil war, it only lasted a day or so but its consequences were felt for a long time thereafter.

What happened there, you did have a democracy, it was a really messy democracy. The constitutional system was indeed unreformed, it was a kind of a mélange of a Soviet-era constitution. There was a constitutional reform project underway in the Supreme Soviet in 1993. Its main architect was a man named Oleg Rumyantsev and he was writing a constitution that was a presidential constitution but with very strong parliamentary powers. At some point, in March 1993, Yeltsin pulled out of that commission, he published his own version of a constitution which would be a very presidential-centric constitution, and he had a referendum declared where there were three questions. I can’t remember exactly what they were, but they were basically doing you trust the parliament or do you trust the president? And he narrowly won it. He used that referendum as his reasons for later in September dissolving the parliament, then besieging it and then shelling it into non-existence. Following that, since he won the war, he rewrote the constitution into the one that we pretty much have today where you have a very strong president. I mean, the parliament isn’t without power but it basically is more decorative than active in terms of shaping policies and addressing the needs of the country. And that had immediate effects. For instance, in 1994 Yeltsin was able to scrawl his name on a decree and start the first war in Chechnya. That would not have happened if he had to walk it by a parliament, but he didn’t. All the privatizations, the loans for shares that came after he won the 1996 elections, all of that was done by presidential decree.

Sputnik: At any point of those events did you feel that the outcome might have been different?

Fred Weir: At the beginning as I said, on October 3 when a huge crowd of people broke the siege of the White House I allowed myself to imagine that it’s over, the political victory has been scored, people have won; the parliament will reconvene and take control of things. I don’t know whether that was realistic or not but I think it was.

Sputnik: Did any of your colleagues share your opinion at the time?

Fred Weir: It’s hard to think back all those years. I think there were some; not most of my Canadian, American, Western colleagues, most of them were totally on Yeltsin’s side, carrying the Yeltsin narrative. It made so much sense to them. These are communists trying to interfere with democracy. They had basically internalized it and they believed it. I thought differently and I did write differently too. I’m sure there were other people and surely in retrospect, most people will agree with me now that the Gorbachev era democracy, that whole experiment, was destroyed in that assault on the White House. Whatever emerged from it may have had features of democracy and it was completely different but it also had features of very strong and dysfunctional authoritarianism.

Sputnik: Did you manage to talk to any Russians during those events or perhaps right after it all happened?

Fred Weir: Of course. On October 4 I was mostly hanging around the precincts of the White House. I couldn’t get inside but I talked to people in the street. They broke down into different groups. There were mainly young intellectuals who supported Yeltsin and said it was necessary. There were others who were in support of the parliament and horrified by seeing tanks on the bridge shelling the parliament. It was a very mixed bag of reactions and in those days most of the politicians who weren’t in the White House were in favor of shelling it. Those would be most of the liberals. They may not have liked the spectacle of the White House burning as it was by the end of the day, at least at the top of the building. But they thought it was necessary. That was a general mood certainly among the liberal intelligentsia who were a much bigger and more powerful force in Russia than they are today. But in retrospect I think that most people have revised their opinions about that, but way too late for that.