A team of scientists at the University of Colorado Boulder has apparently managed to solve yet another mystery of the Earth’s crust by determining why some of the massive tectonic slabs lurking beneath the surface do not act the way they normally would.

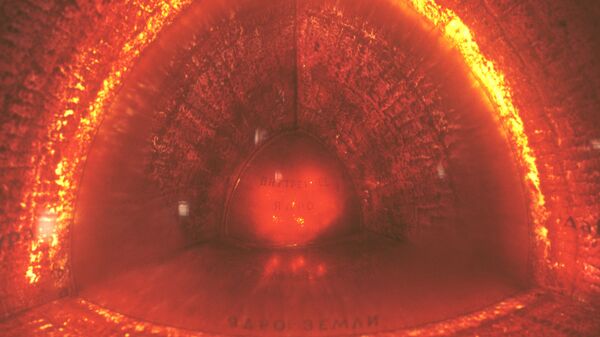

Shijie Zhong, a professor in CU Boulder’s Department of Physics and co-author of the new study, explained that the Earth’s mantle generated tremendous amounts of heat, and so in order to “cool the globe down, hotter rocks rise up through the mantle and colder rocks sink.”

"You can think of this mantle convection as a big engine that drives all of what we see on Earth's surface: earthquakes, mountain building, plate tectonics, volcanos and even Earth's magnetic field," he said.

Zhong’s team now believes that this development may be caused by a thin layer of “less-viscous rock” wedged between the two halves of the mantle at a depth of about 410 miles below the planet’s surface.

"If you introduce a weak layer at that depth, somehow the reduced viscosity helps lubricate the region. The slabs get deflected and can keep going for a long distance horizontally," Zhong remarked.

He also added that with enough time, the slabs will likely break through this layer and continue their journey towards the planet’s core.