The Armistice signed on the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918 was hailed at the time as the long-awaited and prayed for advent of peace after a “war to end all wars”, as the Great War was called by the politicians who had plunged the world into this terrible carnage.

But there was no peace in sight for Russia. Her allies Britain, France and the United States turned their guns on the very people who for three long years from 1914 to 1917 kept scores of German and other Central Powers’ divisions pinned down on the Eastern Front, relieving pressure on Western allies and saving them from an early defeat.

There is a well-worn anecdote in France that Paris was saved from German occupation in September 1914 by Parisian taxi drivers who ferried reinforcements to the front line during the first Battle of the Marne. What this anecdote omits is that at the same time the Russians engaged the Germans in the East forcing them to redeploy their troops, thereby weakening their push for Paris. The battles in East Prussia and Poland cost the Russians dearly but they allowed the Allies to beat back the Germans from the gates of Paris. This became a recurrent pattern for relieving pressure on Western Allies throughout the war.

READ MORE: Merkel Shouldn't Have Been at Armistice Events 'for Winners of WWI' – AfD Leader

The great exertion and sacrifice of the Russian people in helping their Western Allies had exhausted the country and undermined her ability to continue fighting, as her Allies demanded. After two revolutions within six months of each other in 1917 Russia had no choice but to sue for peace with Germany, whose troops occupied large swathes of the country and were marching on the then capital Petrograd. But the hostilities did not end with the signing of peace with Germany in March 1918.

The West cried foul and accused Russia of betraying the Allied cause.

The official excuse for the intervention was to keep up the Eastern Front against Germany and safeguard Western military supplies that had been delivered to Russia as part of the war effort, from falling into German hands. However, having secured those stores the Allies opened them up to the counter-revolutionary White armies and started pouring even more war material onto the bonfire of the Russian Civil war.

As K.W.B. Middleton wrote in his essay Britain and Russia in 1947,

“The Allied invasion of Russia, coming on top of other troubles, caused the same reaction of panic and fury as the Austrian and Prussian invaders of France had produced in the minds of earlier regenerators of humanity.”

Dangerous Adventure

An active and sinister role in orchestrating this invasion was played by a British diplomat and Secret Service agent Bruce Lockhart, whom Prime Minister Lloyd George sent to Russia with a remit to try and find a modus vivendi with Moscow.

Instead, he became the most vocal advocate of intervention in Russia, as he later reminisced in his Memoirs of a British Agent:

“Almost before I had realized it I had now identified myself with a movement which, whatever its original object, was to be directed, not against Germany, but against the de facto government of Russia”.

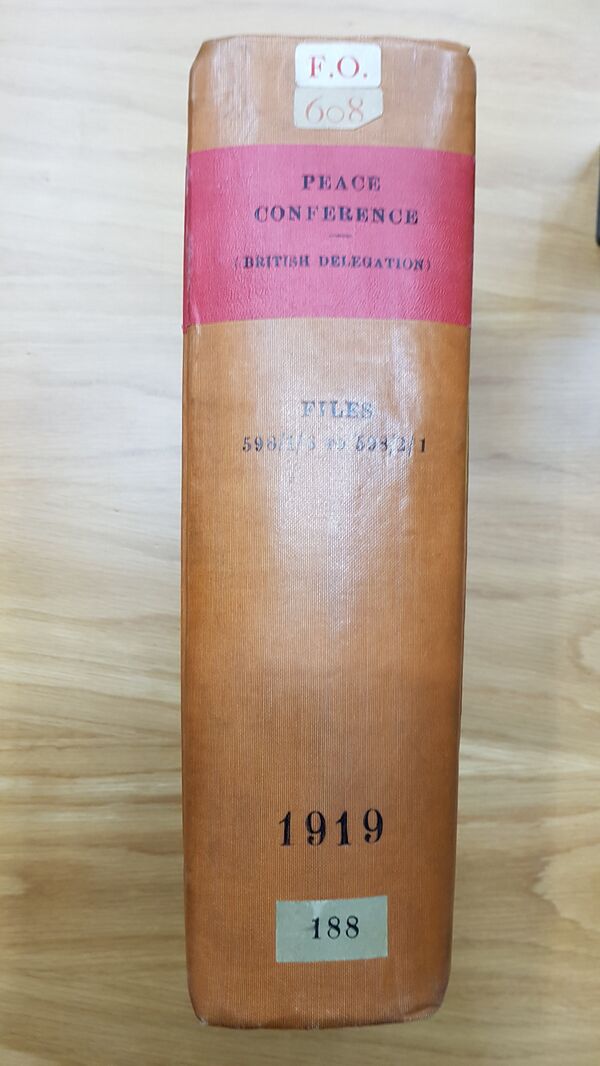

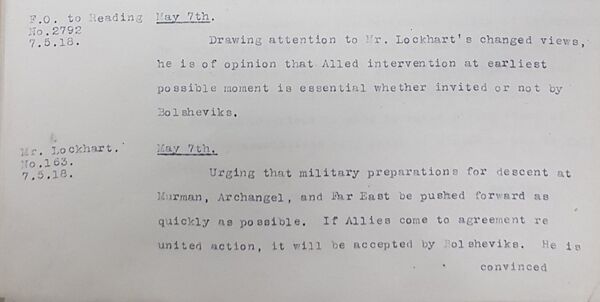

UK government papers held by National Archives in London chronicle his efforts to persuade Americans to give credence to the Anglo-French intervention in Russia by sending in the American troops, which they were initially reluctant to do.

Shortly after the Russian-German peace treaty of March 1918 Lockhart began cabling London with his demands for action in Russia.

“Allied intervention at earliest possible moment is essential whether invited or not by Bolsheviks… Military preparations for descent at Murman, Archangel, and Far East be pushed forward as quickly as possible… Importance of American co-operation is enormous: if denied it becomes a dangerous adventure”.

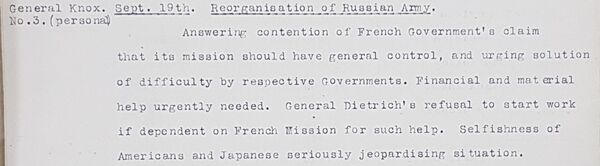

A dangerous adventure it did become, with every foreign power playing their own game in a country being torn apart by civil war, nationalism and separatism, witnessed K.W.B. Middleton:

“Japan was interested only in eastern Siberia and the Pacific coast. The United States was interested mainly in obstructing the Japanese. France was more eager to set up client states to stand guard on Germany in eastern Europe than to encourage a revival of Russian imperialism. Even Britain, the principal supporter of the Whites, was not single minded.

Lloyd George was inconsequent and vague. He did not feel quite sure whether Kharkov was a town or a White general.”

War for British Interests

The news of German surrender on 11 November 1918 was greeted in Moscow with an excitement as great as that displayed in the victorious countries. At last, peace was in sight for Russia as well.

But the victorious Powers decided that despite the defeat of Germany the allied troops, who had been sent to Russia to “protect her from German domination”, should remain there to help one side in the Russian Civil war against the other.

As soon as the Straits were opened, Allied navies entered the Black Sea. A British force landed at Batum; another occupied the oil-rich Baku; and before long the railway connecting the two ports, and then all Transcaucasia, came under British control.

In a deal similar to the Sykes-Picot carving up of the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East, Britain and France divvied up Russia. The British took the Caucasus; the French established themselves in Ukraine and Crimea.

READ MORE: 100 Years On: Sykes-Picot Agreement Still Haunts the Middle East

“At the same time, the Allied armies at Murmansk, Archangel and east of the Volga were maintained, and further aid and comfort was given to the Whites, who were becoming more and more reactionary and less and less representative of any major section of Russian opinion”, wrote Middleton.

“What explanation or justification could there be for this strange manner of exhibiting Allied devotion to the principles of national self-determination and democracy?”

The explanation of Britain’s true motives was given in The Times’ editorial comment on a speech by the then Minister for War Winston Churchill in January 1920:

“If there had been no civil war in Russia we might have had war for interests recognized as unquestionably British… only in far more inaccessible regions than this war… amid every circumstance of disadvantage and inconvenience to ourselves”.

So Britain took full advantage of its ally’s misfortunes. A full year after the Armistice, a press officer at the British War Office was asked by a journalist if Britain was at war with Soviet Russia. The official took refuge in evasion and referred the question up. The reply was: “of course we are at war with Soviet Russia, but as far as the press and public are concerned we are not”.

Gateway to World War Two

As Prime Minister Lloyd George told the House of Commons on 13 Nov 1919: “…between the date of the Armistice and the end of October (1919), in cash and in kind, the value of nearly 100,000,000 pounds has been spent or sanctioned by the United Kingdom on account of assistance sent to Russia [White Armies – NG]. A substantial part of this sum has been or will be added to permanent indebtedness of this country.”

That, according to K.W.B. Middleton was ‘the least expensive part of the policy of intervention’.

“It was inevitable, in any event, that there should be civil war in Russia. And it was inevitable that there should be a gulf, hard to bridge, between capitalist democracy and proletarian dictatorship. …

“But by encouraging and helping the counter-revolutionaries the Allies made the gulf much wider than it otherwise would have been. They awakened in Communist minds and hearts an indelible suspicion, a morbid hostility towards the Western democracies. They obliged the Soviet government in self—defence to do all in its power to stir up trouble for them, with the defeated Central Powers, in their colonial possessions, among their own people at home. They only prolonged the agony of the Whites. They multiplied suffering, bloodshed, devastation in Russia. They stimulated the appetite of her neighbours, and the illusions of every nationalist fraction in the Tsarist Empire. They delayed the settlement of the Continent and postponed, until it was too late, Russia’s return to her due place as a great Power in the councils of Europe. In so doing, they made a large contribution towards the outbreak, twenty years afterwards, of a second World War.”

Will this lesson be on the minds of Western politicians when they pay tribute in Paris to the millions of fallen in their Great military adventure?