Unlike the Bolsheviks who struck separate peace deal with Germany in March 1918, the Whites were intent on honoring Russia's obligations to her Western Allies to fight Germany and other Central Powers to the victorious end. Accordingly, they expected Britain and France to come to their help against the Bolsheviks once Germany was defeated.

They were to be sorely disappointed. Having paid lip service to fighting Bolshevism and supporting fledgling democracy in Russia, the Allies pursued their own imperial interests in the crumbling country. They had no time for the Whites' dream of restoring the ‘one and indivisible Russia'. In Anglo-French view this dream was "reactionary" and they went about helping nationalists and separatists of every hue to break away from the Russian Empire, while making sure their own empires grew.

Carving up Russia

In the same manner as Britain and France divided the Ottoman Empire between them in the Sykes-Picot deal, the two WWI victors agreed on spheres of influence in Russia. The British claimed the North, the-oil rich Caucasus and Central Asian approaches to British India; the French took over Ukraine and Crimea.

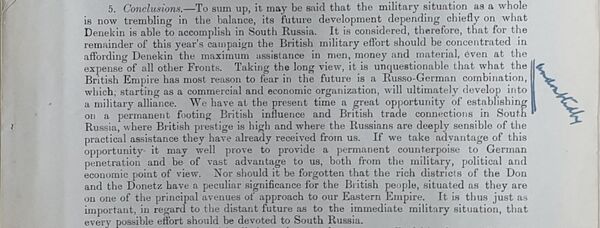

In a secret memorandum on the military situation in Russia the British General Staff didn't mince their words as to the aims of the British military intervention in South Russia, as well as in what is now East Ukraine:

"Nor should it be forgotten that the rich districts of the Don and the Donetz have a peculiar significance for the British people, situated as they are on one of the principal avenues of approach to our Eastern Empire. It is thus as important, in regard to the distant future as to the immediate military situation, that every possible effort should be devoted to South Russia.

"Taking the long view, it is unquestionable that what the British Empire has most reason to fear in the future is a Russo-German combination, which, starting as a commercial and economic organization, will ultimately develop into a military alliance.

Secret memorandum aside, the official excuse for the intervention that began first in Russia's North and Far East in the summer of 1918 was to keep the Eastern Front and protect the Allied war stores in Russia from falling into German hands. However, the intervention started in earnest only after the defeat of Germany in November 1918 and therefore lost all semblance of legality.

Scrap Value

In late November 1918, just under a fortnight after the Armistice, the Anglo-French navies took advantage of the opening up of the Turkish straits and seized Russian Black Sea ports one by one. In a repeat of the 1853-56 Crimean war scenario British, French and Italian warships docked at Sevastopol. Twenty transport ships were used to bring Allied troops from the defunct Salonika front to the new front in South Russia.

The White Volunteer Army under General Denikin hailed the arrival of the Allies. The Whites were desperate for support, especially for weapons and munitions as Russian munitions factories were in Red hands. But they came in for a shock. The British dumped rubbish on them.

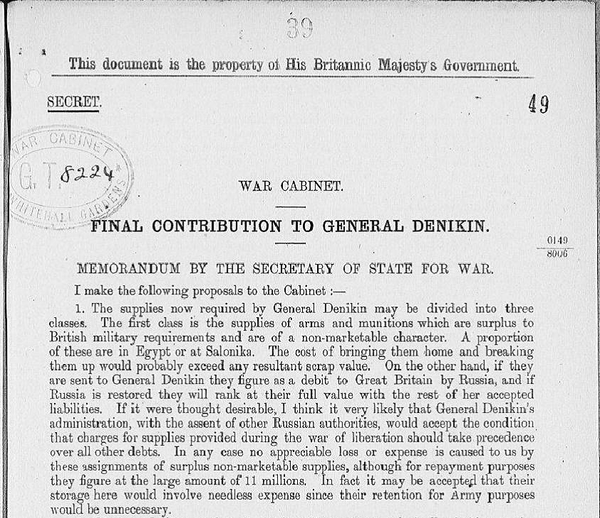

A secret memorandum by the then Secretary for War Winston Churchill, held at the National Archives in London, reveals a cynical plan to saddle Russia with useless scrap and make her pay for it.

Churchill suggested dumping "non-marketable" leftovers from the British war supplies on the White Russian armies and making them pay for what was of little value even as scrap. In the words of one British commander,

"[this] obsolete material… in my opinion would not be worth the expense of keeping the men to bring it home for sale".

No wonder the Whites lost out to the Reds who relied on Russian weapons factories in their hands.

Unlike obsolete weapons, "part-worn clothes and boots" of British soldiers did, in Churchill's view, have "marketable value". Hence, the British did not want to be "too generous" in dispensing second-hand outfits to the rag-tag White Volunteer Army. Churchill came up with an ingenious plan for minimizing the cost of delivering those limited supplies to the White armies in the South of Russia.

"In this connection it might be possible to transship from North Russia to South Russia some 60 locomotives of Russian origin and gauge, involving no cost save that of the sea journey".

That the locomotives were Russian property did not apparently cross Churchill's mind. Maybe he viewed Russia as yet another British colony.

‘Unfit for Self-Government'

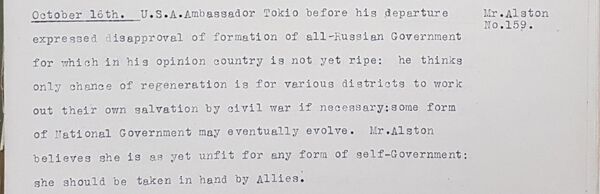

Indeed, British diplomatic cables of the time, also held at The National Archives in London reveal the true attitude of Western politicians to Russia's sovereignty and their plans for her future.

On October 16, 1918 a British cable from Tokyo quoted the departing US Ambassador as having

"expressed disapproval of formation of all-Russian Government for which in his opinion country is not yet ripe: he thinks only chance of regeneration is for various districts to work out their own salvation by civil war if necessary [sic!]…

[Ambassador] believes she [Russia] is as yet unfit for any form of self-government: she should be taken in hand by allies".

The "assistance" provided by the Anglo-French allies to the White Volunteer Army of General Denikin was not nearly enough to defeat the Red Army but just about right to keep the Whites fighting and prolong the civil war in Russia for much longer then was necessary.

The Anglo-French allies refused to hand over to the Whites the Russian warships that they seized from the Germans under the terms of the Armistice, as General Denikin lamented in his memoirs, The Russian Turmoil.

"English, French, Italian and even Greek flags were raised on the better of those warships", Denikin wrote. "All seaworthy ships were made to sail to Turkey to be interned there. Our plea to send at least a couple of destroyers to Novorossisk [a Black sea port under Denikin's control — NG] was abruptly turned down by the Allied Navy commander."

The White army had to improvise with "makeshift warships" by putting some cannon on rusty tugs and barges. When the Bolsheviks were poised to overrun Crimea the Allied commander gave orders to destroy whatever the Allies could not evacuate.

"The French and English sank and blew up munitions kept in the Sevastopol stores, hacked up batteries and fuel tanks of submarines, destroyed navigation equipment and took away cannon triggers. The Allies' actions looked more like liquidation then the start of an anti-Bolshevik campaign", General Denikin wrote.

"We did not get any real help from France, neither in the form of solid diplomatic support, nor in credits, nor in supplies".

However, the French were quick to demand that the Whites compensated French businesses for damages incurred as a result of the Russian revolution.

The British went a step further by piling up new debts on Russia. In the abovementioned secret memorandum Churchill played a "games of numbers"

And in return for this modest expenditure, said Churchill, "the means will be provided of influencing Russian policy in a wise direction and in a direction friendly to Great Britain, to say nothing of the possibility of the repayment of our whole great Russian debt when Russia is again restored".

His views were echoed by the British General Staff:

"We have at the present time a great opportunity of establishing on a permanent footing British influence and British trade connections in South Russia, where British prestige is high…"

Barren Victories

Whatever prestige the British used to have in Russia they managed to ruin it within a year of their intervention, as a British Parliamentary Committee opined:

"There is evidence to show that, up to the time of military intervention the majority of the Russian intellectuals were well disposed towards the Allies, and more especially to Great Britain, but that later the attitude of the Russian people towards the Allies became characterised by indifference, distrust and antipathy."

One year after the arrival of British troops in South Russia they had to evacuate. The British Prime Minister David Lloyd George told his audience at Guildhall in November 1919 that Russia was a dangerous land to intervene in, as the British had discovered it in Crimea:

"Our troops are out of Russia. Frankly I am glad. Russia is a quicksand. Victories are easily won in Russia, but you sink in victories, and great armies and great Empires in the past have been overwhelmed in the sands of barren victories."

The long term consequences of the intervention, wrote American Historian William Henry Chamberlin who was the Moscow correspondent of The Christian Science Monitor in the 1920-30s, "were to poison East-West relations forever after, to contribute significantly to the origins of World War II and the later Cold War, and to fix patterns of suspicion and hatred on both sides which even today threaten worse catastrophes in time to come."