"It's really a puzzle," agreed Alan Stern, NASA's New Horizons principal investigator, cited by Gizmodo.

"I call this Ultima's first puzzle," Stern remarked, adding, "why does it have such a tiny light curve that we can't even detect it?"

Stern and his team expressed confidence that images retrieved from the close flyby would reveal the source of the mystery and observed the excitement following the outbound spacecraft's journey to the stars.

"I expect the detailed flyby images coming soon to give us many more mysteries, but I did not expect this, and so soon," he noted.

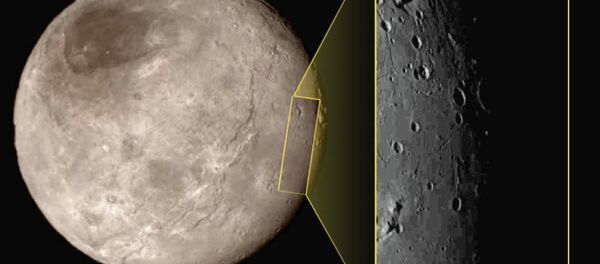

Similar in composition to the Asteroid Belt between Mars and Jupiter but far larger, the Solar System's Kuiper Belt lies beyond the eight major planets, beginning at the orbit of Neptune (approximately 30 AU) to about 50 AU away from the Sun.

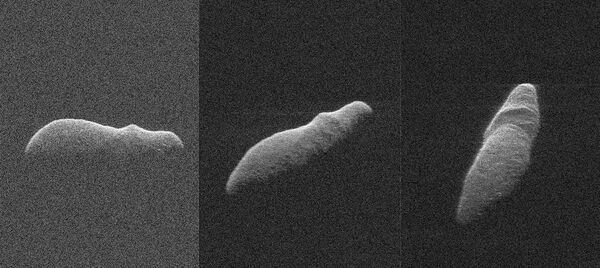

The New Year's Day flyby, at a staggeringly close distance of just 2,200 miles (3,500 kilometers), will map surface composition and morphology of the 25-45 kilometer-wide Ultima Thule, as well as looking for any coma, rings, or orbiting moonlets,

Several theories for the KBO's lack of light curve have been put forth.

Southwest Research Institute mission scientist Marc Buie suggested that the rotational point of Ultima Thule could currently be aligned directly toward the NASA spacecraft as it approaches. From that perspective, the spacecraft would not detect the shifts in brightness as the irregularly-shaped rock tumbles through space.

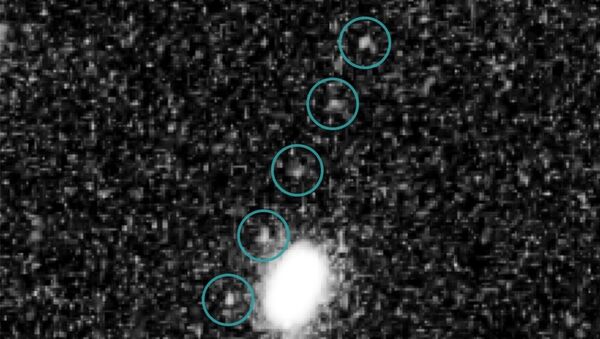

University of Virginia researcher and New Horizons assistant project scientist Anne Verbiscer, offered that Ultima Thule could be occluded by multiple little moons — each tumbling object producing a discrete light curve — creating, in her words: a "jumbled superposition of light curves."

There are no known examples of this kind of celestial object within our Solar System, however, making the idea unlikely.

Naturally, social media and civilian NASA observers have chimed in with a prominent meme along the lines of: "I'm not saying it's aliens, but…"