An underground treasure trove of ancient Mayan artefacts – the “cave of the jaguar god,” – was first discovered by local farmers in 1966 under the ancient city of Chichén Itzá, Mexico, Vice’s Motherboard reported. For unknown reasons the cave was walled off and only now archaeologists have gained access to it, revealing hundreds of items dating back more than 1,000 years, such as decorative plates, grinding stones, incense holders, and figures of Balamkú, the jaguar god.

"Balamkú will help rewrite the story of Chichen Itzá,” said Guillermo de Anda, co-director of Great Maya Aquifer Project (GAM) and an archaeologist at the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), at a press conference in Mexico City on Monday. The hundreds of archaeological artifacts “are in an extraordinary state of preservation,” he added.

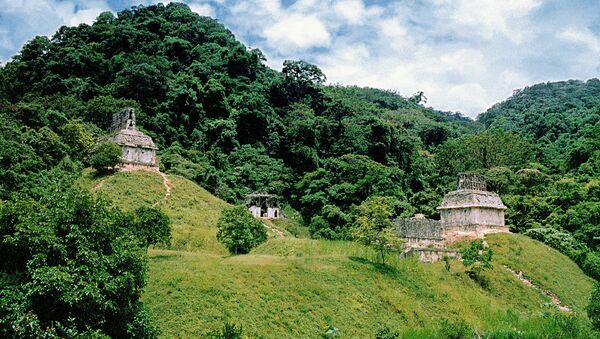

READ MORE: Laser Reconnaissance Uncovers Ancient Mayan City in Guatemalan Jungle

James Brady, co-director of GAM and a professor of anthropology at California State University in Los Angeles, has been puzzling over an archaeologist named Víctor Segovia Pinto’s decision to seal the cave with rocks back in 1966.

“[Segovia] may have already been committed to other projects and knew that he did not have the time or resources to do it. That may have been why he told them to close it up and leave it,” he suggested.

Segovia, now deceased, had filed a small internal report about the discovery with INAH. But the cave was otherwise overlooked for five decades until de Anda was tipped off to it by Luis Un, 68, a local resident and one of the people who first explored Balamkú in 1966, when he was still a teenager. He was the one who led de Anda and his colleagues to the cave entrance last year.

“We’ve never had an opportunity quite like this where everything is really intact and guarded and it’s not a salvage operation,” Brady said. “So, we want to go slowly and make this a model cave project.”

The religious significance of the place is made evident by the presence of a “sacbe,” a white road that connects the sinkhole to the main city, as it is a sign that the cave played an important role in ancient Mayans’ lives.

Researchers have already entered and mapped out many of the cave’s passageways above the water table, squeezing through crawl spaces only 40 centimetres wide in some places. Eventually, they plan to explore the underwater portions of the cave as well.

“It’s never over until you come to the last dead end,” Brady said, “and we’re not there yet.”